First Meeting of the Westborough History Working Group. Wednesday, Nov. 6 at 2:00 p.m. at the Westborough Public Library. Do you want to help the Westborough Center with its historical documents and records? Come to this inaugural meeting, where we will start adding dates to historical photographs that lack them and then plan how we want to go forward in the future. If you plan to attend, please e-mail Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian, at avaver@town.westborough.ma.us, so that we can adequately plan space for us to work.

Month: October 2019

How Does History Connect Westborough and India?: Imperial Administration and Rule

Note: The following is the sixth in a series of eleven weekly posts that present my attempt to answer the question, “How does history connect Westborough and India?” See the Introduction for an overview of the series and to start reading it from the beginning.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian, Westborough Public Library

Imperial Administration and Rule

After near complete British victory in the Seven Years’ War, England was now responsible for administering two colonial empires on opposite sides of the globe with differing governing needs. The fact that America was populated with British subjects did not exactly play to England’s advantage, because these citizens automatically assumed that they had a right to direct participation in their government and could not be ruled with an authoritative hand. But for the most part, the British government tended to interfere in the American colonies only in matters of trade and commerce, because they were more concerned with European foreign policy due to fear of falling back into war with France at any given time. The Americans, on the other hand, were obsessed with following news about the overseas affairs of England in order to discover clues about British intentions for ruling its colonies.

Over in Asia, granting Indians the right to a representative government was out of the question, since doing so would undermine Britain’s economic goals. Instead, the British developed an administrative system whereby officials from the East India Company—many of them former military generals, including the Earl of Cornwallis, who surrendered to Washington at Yorktown to end the American Revolution—ruled India and collected taxes both to pay for their rule and to profit from the arrangement. The East India Company now transformed itself into being less of a trading company and more of a military and administrative power headed by a group of oligarchs who sought to expand British control into other areas of India beyond Bengal. And because the wealth generated in India was so much greater in comparison with the American colonies, the British were much more attuned to the political situation in the East than they were in the West.

by Robert Home

(National Army Museum, https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1976-11-86-1)

This painting shows General Lord Cornwallis—who had surrendered to General George Washington at Yorktown to end the American Revolution and was now serving as Governor-General of India—receiving two of Tipu Sultan’s sons as hostages after the 3rd Mysore War (1790-1792). Cornwallis led British troops in capturing large sections of Mysore in southern India, demanded a hefty financial settlement, and took the sons hostage to ensure that Tipu carried out the treaty to end the war. The sons were returned in 1794. In a show of propaganda, the artist, who appears in the far left-side of the painting, depicts Cornwallis as a paternalistic ruler.

* * *

Read the next post in the series: Taxes.

Westborough-India Series Bibliography

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Bunker, Nick. An Empire on the Edge. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Collingham, Lizzie. Taste of Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Darwin, John. Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Eacott, Jonathan. Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600-1830. Chapel Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, 2016.

Frankopan, Peter. Silk Roads: A New History of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 2015.

Freeman, Joshua B. Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Schama, Simon. Civilizations. PBS television series, 2018. http://www.pbs.org/civilizations/home/.

Vaver, Anthony. The Rebellion Begins: Westborough and the Start of the American Revolution. Westborough, MA: Pickpocket Publishing, 2017.

Wilson, Jon. The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India. New York: Public Affairs, 2016.

How Does History Connect Westborough and India?: War and Globalism

Note: The following is the fifth in a series of eleven weekly posts that present my attempt to answer the question, “How does history connect Westborough and India?” See the Introduction for an overview of the series and to start reading it from the beginning.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian, Westborough Public Library

War and Globalism

In 1754, when the French and Indian War broke out and pitted the British-held American colonies against New France for control of North America, Westborough sent at least six soldiers to support the British effort (records of who fought in the war and exactly how many from Westborough have since disappeared). This armed conflict soon became part of the global Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), which involved every major European power and spanned five continents.

While the British and French fought in North America, the French also threatened English positions in India. When the British finally gained decisive victory on both sides of the globe, the Treaty of Paris that officially ended the war granted Britain all of North America east of the Mississippi and forced the French both to abandon any claims to South India and to withdraw its military presence from Bengal. The British suddenly controlled vast parts of the world, but their victory also overextended their ability to administer them, so any action or crisis in one area of the world had the potential to expose a weakness in another.

Victory in the Seven Year’s War handed the British East India Company near monopolistic control over Indian trade, along with the prospect of acquiring more and more influence in the region as the reign of the Mughal Empire deteriorated. With expanded market possibilities for Indian goods, England now aimed to sit at the hub of global trade in the way that India did in Asia under the Mughal Empire before British arrival. This “Indianization” of British trade had a broad effect on the type of goods that were both produced and consumed, and in short time, the British targeted the American colonies as a major market for these worldly goods. Various forms of cotton cloth, shawls, cane and lacquered furniture, aprons, and umbrellas became widely available and fashionable, while tea, curry, pepper, and other spices expanded food palettes throughout the British Empire.

(Westborough Public Library, http://www.westboroughcenter.org/exhibits/reed-collection-discoveries/)

The letter reads:

Kenterhook May ye 14th 1757

Loving wife these Lines are to Inform you that I am got to Kenterhook and am In good helth and I Can give No account when or where I Shall march Next there is a [T reant[?] story that we are to go to the Lake But nothing sartain and I would acquaint you that all that Came from Westborough are in helth give my love to the children No more at present So I Remain Effectionate Husband hopeing that we Shall Live So whilst apart that if we Never meet here on Earth that at Last we Shall meet In heaven

Joseph Woods

Brother Tuller these may give you account of my Afairs So I give my Love to you and my Sister and Remain your Loving friend

Joseph was killed in action shortly after writing this letter during the Battle of Lake George in the French and Indian War.

(British Library, http://www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/large126697.html)

This document lists textiles purchased in Bengal in 1730 by the East India Company, which then exported them to England and other parts of the world, including colonial America.

(Colonial Williamsburg, Acc. No. 2007-96, https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org)

Indian cottons could only be brought into England for re-export, even though the British had gained control of cotton production and distribution. This fragment of painted white chintz cotton was imported to the American colonies from India. The American colonies served as an important market for Indian cottons because their sale on the open market in England was illegal, so as to protect British textile manufacturers from foreign competition.

Mention of “calico” (Indian cotton) in Rev. Ebenezer Parkman’s Diary:

1740 May 2 (Friday). Rainy. Ensign Maynard here who had been to Boston and brought 6 3/4 Yards Callico for Judith and [illegible] from Mr. Jenison for me.

1770 June 7 (Thursday). Messrs. Stone and Smith (I hear by Sophy, who rode to Mr. Stones to get a Callico Gown made).

1772 July 1 (Wednesday). Breck is White-Washing the House. My Wife makes me a dark-figured Callico Gown, which is a present of Brecks to me.

1772 July 9 (Thursday). Several Persons assist my Daughters in Quilting an handsome Callico Bed-Quilt, viz. Mrs. Hawes, Zilpah Bruce.

* * *

Read the next post in the series: Imperial Administration and Rule.

Westborough-India Series Bibliography

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Bunker, Nick. An Empire on the Edge. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Collingham, Lizzie. Taste of Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Darwin, John. Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Eacott, Jonathan. Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600-1830. Chapel Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, 2016.

Frankopan, Peter. Silk Roads: A New History of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 2015.

Freeman, Joshua B. Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Schama, Simon. Civilizations. PBS television series, 2018. http://www.pbs.org/civilizations/home/.

Vaver, Anthony. The Rebellion Begins: Westborough and the Start of the American Revolution. Westborough, MA: Pickpocket Publishing, 2017.

Wilson, Jon. The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India. New York: Public Affairs, 2016.

How Does History Connect Westborough and India?: Settlement and Colonization

Note: The following is the fourth in a series of eleven weekly posts that present my attempt to answer the question, “How does history connect Westborough and India?” See the Introduction for an overview of the series and to start reading it from the beginning.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian, Westborough Public Library

Settlement and Colonization

Whether the indigenous people of North America realized it at the time or not, contact with the English in the seventeenth century forced them into competing in the global trade market. At first, Native Americans traded deerskins and furs for iron tools, guns, and ceremonial objects. But when new settlers lost interest in the deerskins and furs, all that the native peoples had left to trade was land. Farmers quickly bought up their land, cleared it, and grew as many crops on it as possible in order to maximize profits.

These English settlers never intended to adopt, or even adapt to, the indigenous lifestyle they encountered and instead sought to preserve their European culture and way of life as much as they could. In 1704, tensions between British settlers and Native Americans played out to tragic consequences in Westborough. Five boys from the Rice family were working out in the field close to where the High School now stands when a group of ten members of the Mohawk tribe who had traveled south from Canada killed one of the boys and seized the other four. They carried the four boys back to Canada in order to replenish the dwindling number of males in their tribe due to plague and a consequent low birth rate. Two of the boys ended up adopting the indigenous way of life and staying with the tribe for the rest of their lives, and one of them even became a chief of the Iroquois nation.

In contrast to their experience in North America, when the British first landed in India they encountered the Mughal Empire, the most developed civilization in the world at the time. India’s wealth came from its incredible production of rice, cloth, and other goods, in addition to its advantageous geographical position in south-central Asia, which allowed it to control much of the trade in luxury goods carried out among China, Japan, Persia, and other Asian countries.

The monarchs and ministers in India saw British traders as “rude hairy barbarians” who dressed in smelly woolens and linens. In order to demonstrate goodwill with the Mughal emperor, British merchants began dressing in the same clothing as his courtiers and adopting other Indian customs, such as smoking hookas, in an attempt to cultivate more advantageous trade relations. This adoption of local Indian customs in turn set fashion trends back in England and in colonial America, where Indian-inspired dress and decorative arts became all the rage.

The charter for the Massachusetts Bay Colony granted by Charles I included the authority to make and use a seal. The final design featured a Native American holding a downward pointing arrow as a sign of peace and saying, “Come over and help us.” The seal clearly displays a sense of cultural superiority to the indigenous people that English colonists brought with them to North America.

(Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/storyofriceboysc00park/page/n21)

by Dip Chand

(Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O16731/painting-portrait-of-east-india-company/)

Company paintings were made by Indian artists for British subjects, and this one is probably of William Fullerton of Rosemont who served in the East India Company starting in 1744. Note he is shown lounging on a carpet while enjoying a hookah.

* * *

Read the next post in the series: War and Globalism.

Westborough-India Series Bibliography

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Bunker, Nick. An Empire on the Edge. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Collingham, Lizzie. Taste of Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Darwin, John. Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Eacott, Jonathan. Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600-1830. Chapel Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, 2016.

Frankopan, Peter. Silk Roads: A New History of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 2015.

Freeman, Joshua B. Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Schama, Simon. Civilizations. PBS television series, 2018. http://www.pbs.org/civilizations/home/.

Vaver, Anthony. The Rebellion Begins: Westborough and the Start of the American Revolution. Westborough, MA: Pickpocket Publishing, 2017.

Wilson, Jon. The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India. New York: Public Affairs, 2016.

How Does History Connect Westborough and India?: Global Trade

Note: The following is the third in a series of eleven weekly posts that present my attempt to answer the question, “How does history connect Westborough and India?” See the Introduction for an overview of the series and to start reading it from the beginning.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian, Westborough Public Library

Global Trade

British intention to exploit the resources of North America in the early seventeenth century did not go as originally planned. Discovery of gold and silver never panned out, since there was little to find or take from the native population, and the natural resources available in New England turned out to be similar to those back in Britain.

The British lack of success in America was mirrored on the other side of the globe when their goods failed to generate much trade interest in India and other parts of Asia. The manufacturing skill of the British fell far below that of Eastern artisans, and the woolens and linens produced in England paled next to the luxurious cottons and silks made in India. Still, Britain’s advantageous geography off the western shore of continental Europe put them at the crossroads of major sea-going trade routes, and so the country was well positioned to serve as a geographic connector between the Old and New Worlds.

Once the British used their naval superiority to gain command of the seas, they turned their attention to becoming players in the booming global commodities trade. In the West, they took the raw materials they acquired in the Americas—such as tobacco from Virginia and sugar from the Caribbean—manufactured them into processed goods back in England, and then exported the goods to continental Europe and other countries around the world. In the East, the East India Company inserted itself into trade between India and China by acquiring cotton in the former and selling it to the latter for tea, which was then shipped to England and colonial America.

By the nineteenth century, British domination in world trade and shipping allowed more and more local manufacturers to tap into global markets. When the National Straw Hat Factory in Westborough became an international company by distributing its hats throughout the world beginning in the late nineteenth century, it could do so only because the British first created a global trade network that connected India with North America beginning in the seventeenth century.

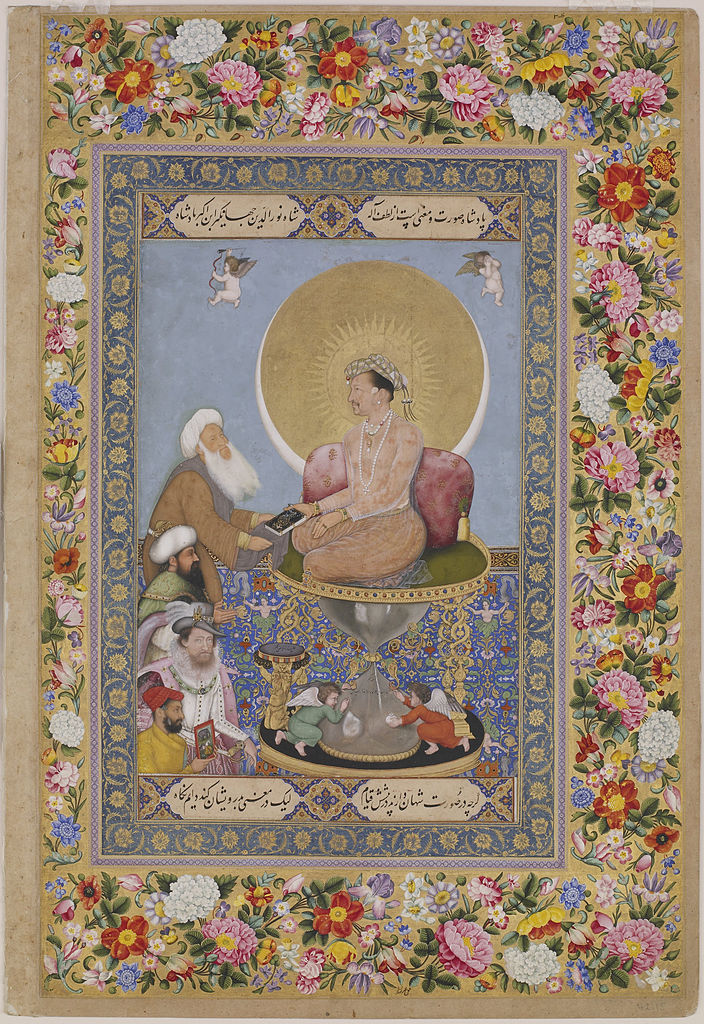

by Bichitr (active between ca. 1615 – 1640)

(Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bichitr_-_Jahangir_Preferring_a_Sufi_Shaikh_to_Kings,_from_the_St._Petersburg_album_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

In this image of Jahangir, the Mughal Emperor, King James I sits below the emperor as third in the hierarchy, with both Shaikh Salim, an Islamic mystic, and the Ottoman Emperor above him. Bichitr, the artist of the work, sits at the bottom in a self-portrait.

(Westborough Center for History and Culture, Westborough Public Library)

The National Straw Works (1871-1917) located on East Main Street in Westborough, MA, near where the Bay State Commons sits today, exported straw hats and other straw goods throughout the world. Such markets were first created by the British and other European powers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

* * *

Read the next post in the series: Settlement and Colonization.

Westborough-India Series Bibliography

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Bunker, Nick. An Empire on the Edge. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Collingham, Lizzie. Taste of Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Darwin, John. Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Eacott, Jonathan. Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600-1830. Chapel Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, 2016.

Frankopan, Peter. Silk Roads: A New History of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 2015.

Freeman, Joshua B. Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Schama, Simon. Civilizations. PBS television series, 2018. http://www.pbs.org/civilizations/home/.

Vaver, Anthony. The Rebellion Begins: Westborough and the Start of the American Revolution. Westborough, MA: Pickpocket Publishing, 2017.

Wilson, Jon. The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India. New York: Public Affairs, 2016.

Architecture Tour Booklet

If you plan to attend the architecture tour on Sunday, make sure you download the booklet that will be used during the tour. Hope to see you there!

* * *

British Influences on Westborough’s Architecture Walking Tour, Sunday, October 6, 2019, 1:00 p.m. at the Library steps. Join R. Christopher Noonan and Luanne Crosby as they talk (and sing!) about the interplay and influences of the British Empire’s architectural traditions on Westborough’s buildings, neighborhoods, and even cemetery design. This program is part of the Westborough History Connections series on Westborough and India under the British Empire.

Upcoming Westborough Center Program Reminders

Tonight (Weds., 10/2):

Introduction to Indian Classical Music, Its Overlaps and Differences with Western Music, Wednesday, October 2, 2019 at 6:30 p.m. in the Library Meeting Room. Learn and engage in a 90-minute interactive workshop on Indian classical music. This program is part of the Westborough History Connections series on Westborough and India under the British Empire.

Sunday (10/6):

British Influences on Westborough’s Architecture Walking Tour, Sunday, October 6, 2019, 1:00 p.m. at the Library steps. Join R. Christopher Noonan and Luanne Crosby as they talk (and sing!) about the interplay and influences of the British Empire’s architectural traditions on Westborough’s buildings, neighborhoods, and even cemetery design. This program is part of the Westborough History Connections series on Westborough and India under the British Empire.

How Does History Connect Westborough and India?: Charters and Private Enterprise

Note: The following is the second in a series of eleven weekly posts that present my attempt to answer the question, “How does history connect Westborough and India?” See the Introduction for an overview of the series and to start reading it from the beginning.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian, Westborough Public Library

Charters and Private Enterprise

In the sixteenth century, the English watched as the Spanish filled their coffers with gold and silver after conquering South America. They also saw the Portuguese become fabulously rich after discovering shipping routes around the south of Africa to India, which provided them with easy access to pepper and other valuable spices that could be traded back in Europe.

No longer wanting to sit on the sidelines as other European powers developed new trade relations and created colonies to enrich themselves, the British government issued charters at the beginning of the seventeenth century to two groups of English businessmen to explore and exploit new lands and trade routes. These two charters—one for exploring North America in the hope of finding raw materials similar to what the Spanish found in South America and one for initiating trade in Asia—set the stage for British rule in both Westborough and India.

(Commonwealth Museum, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mus/treasures-gallery.html)

In 1629, King Charles I issued this charter to a “Councell established at Plymouth.” The charter authorized them to take possession of lands and all that they offered (“Firme Landes, Soyles, Groundes, Havens, Portes, Rivers, Waters, Fishing, Mynes, and Minerals”) that were “not then actuallie possessed or inhabited, by any other Christian Prince or State.” The result was the creation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Note how conquest underlies the purpose of the charter. A complete transcription of the Charter can be found here: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass03.asp.

(National Arms and Emblems, http://www.hubert-herald.nl/BhaHEIC.htm)

A royal charter issued by Queen Elizabeth I gave permission to a group of entrepreneurs to create the East India Company for “the Increase of our Navigation, and Advancement of Trade of Merchandize” with countries east of Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. The Company’s first trip to India was in 1608. A complete transcription of the Charter can be found here: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Charter_Granted_by_Queen_Elizabeth_to_the_East_India_Company.

* * *

Read the next post in the series: Global Trade.

Westborough-India Series Bibliography

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Bunker, Nick. An Empire on the Edge. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Collingham, Lizzie. Taste of Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Darwin, John. Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Eacott, Jonathan. Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600-1830. Chapel Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, 2016.

Frankopan, Peter. Silk Roads: A New History of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 2015.

Freeman, Joshua B. Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Schama, Simon. Civilizations. PBS television series, 2018. http://www.pbs.org/civilizations/home/.

Vaver, Anthony. The Rebellion Begins: Westborough and the Start of the American Revolution. Westborough, MA: Pickpocket Publishing, 2017.

Wilson, Jon. The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India. New York: Public Affairs, 2016.