This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Native Americans in Westborough History, Part II: The Legend of Hoccomocco and Native American Water Use

Third graders in Westborough are quite familiar with the Legend of Hoccomocco, a Disneyesque story about a pond here in town that eventually became a Superfund Cleanup Site. The fanciful story seems to be tailor-made for “teaching” young students about the Native Americans who once inhabited the land where our town now sits, so it often holds a central place in the third-grade local history curriculum of the Westborough schools.

In a nutshell, the story is about two Indian warriors vying for the hand of an Indian maiden, but before she marries her chosen suitor, the rival, in a fit of jealousy, drowns her in Hoccomocco Pond. However, the Hobomak, an evil spirit that inhabits the waters, annually rises up in a flame to taunt the murderous rival until the third year when it finally avenges the maiden’s murder by dragging him down into the depths of the waters where he disappears. This story was first published in 1838 by Horace Maynard in Horae Collegianae, an Amherst College undergraduate publication. Maynard claims that he faithfully reproduced the story as it was told to him by “an old Indian, the last of his tribe,” who used to visit his family’s house when he was very young and tell “strange legends of his people, more or less embellished as he drank his cider,” in the evenings around a fire.

Rearing its head once again here is the myth of the “last Indian,” which we already looked at in relation to Jack Straw in last month’s newsletter. In her 1889 book, The Hundredth Town, Glimpses of Life in Westborough, 1717-1817, Harriette Merrifield Forbes further perpetuates this myth when she claims, “More than two hundred years have passed away since the Indian, unmolested, roamed through the wilderness of Wabbequasset—land of the Nipmucks—the Whetstone country. Nearly every trace of him has disappeared” (9). Yet, in the same book she contradicts herself when she speculates that Andrew Brown, an Indian who lived in town, was the person who told the Legend of Hoccomocco to the Maynard family and goes on to provide details about Brown and his family. She then proceeds to include information about other Native American families and their offspring who were still living in Westborough at the time she wrote her book.

Curtiss R. Hoffman notes in his book, People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts, that southern New England hosts several low-lying, glacial ice-block lakes with place names of “Hoccomocco” or “Hobbamock” or similar variations. The pond in Westborough itself has other spelling iterations, such as “Hocomonco” or “Hocomoco.” Hoffman goes on to relate that a colleague of his, who is a cultural anthropologist and folklorist and has studied this legend in some detail, discovered that the story is repeated in almost every community in New England that has a lake or pond with such a place-name. The source of all these legends, it appears, are members of local Chambers of Commerce in the late 1800s who were trying to enhance the image of their towns. The tell that ties them all together is the inclusion of a preposterous side-story that Captain Kidd buried his treasure on the shores of these lakes or ponds—a side-story that also appears in Maynard’s published story in 1838. Most likely, Maynard’s story served as the original source for the legends told by these various Chamber of Commerce groups. Maynard never specifically locates the story he wrote in Westborough, which is probably why it was able to spread to other places that had lakes or ponds with similar names.

But is the story authentic? If we are to believe that Andrew Brown (or perhaps some other Indian) told the legend under the influence of hard cider (at another point in her book Forbes accuses Brown of being a drunk [pp. 171-172]), such family gatherings around the fire would have occurred in the 1820s or perhaps the 1830s, given Maynard’s age when he wrote the legend. According to Forbes, Brown and his family lived on Flanders Road, so they more or less had assimilated into a more European mode of living by “making baskets” and, according to Maynard, re-bottoming kitchen chairs. Was Brown intending to tell an “authentic” Native American legend around the fire, or was he using one or more tales from his background as inspiration to create a new story that would appeal to the Maynard family? Even Maynard indicates that the more cider his visitor drank, the more embellished the stories became. How accurately did the Amherst student reproduce the story from memory? And at any event, was accuracy his true objective in publishing the story, or was he himself embellishing it for the college publication, much like Brown supposedly did around the fire, despite Maynard’s insistence that “one of his [visitor’s] tales I have here faithfully recorded”—a common trope in tall tales or urban legends?

I am not a folklorist, nor an expert in Native American life and mythology, but every time I read the Legend of Hoccomocco, it rings hollow to me. Even if the kernel of the story is truly Native American—although I have my doubts—Maynard clothes it with descriptions and words that are distinctly European. He describes the Indian maiden in sexualized terms—as “the belle of her tribe, and, like all belles, an incorrigible coquette”—and in no way does he portray in his story the more egalitarian relations between the sexes in Native American life. He uses the language of European royalty to describe the status of the main characters within their Native American social organization. He depicts the impending wedding ceremony as though it will take place in a Western church, complete with a “priest” who will bind the two lovers. Descriptions of the warriors’ attire always include “human scalps.” Direct communication between humans and animals who occupy the same space and learn how to coexist with one another—a common feature in most Native American tales and legends—is entirely absent. In fact, throughout the story the animal world only appears as though it is in confrontation with the human world. And the only magic that occurs—again a common theme in Native American legends—is the appearance of the evil Hobomok at the end.

Just like we did with the story of Jack Straw, we may ask: after we eliminate all the ambiguities that surround this tale and the circumstances under which it was related, what are we left with? Not much. But the feature of the story that does ring true is the importance of water and swamps to Native American life in our area and the evil spirit that is associated with them.

“Nipmuc” literally means “people of the fresh water,” which demonstrates the importance of water to the Nipmuc’s livelihood and being. Swamps were both an important food source and a sacred place for Native Americans before European arrival. According to Hoffman, these waters “were associated with Hoccomock/Hobbamock, a trickster figure who was nevertheless responsible for the fertility and productivity of the local group, as well as shamanistic powers for individuals. That he was unreliable and capable of bringing famine and bad fortune is perhaps an analogy to the uncertain ground to be found in his domain.” Hoffman goes on to note that during the Contact Period with Europeans, as the relationship between the two groups became more fraught, the Hobbamock begins to take on characteristics of an English gentleman.

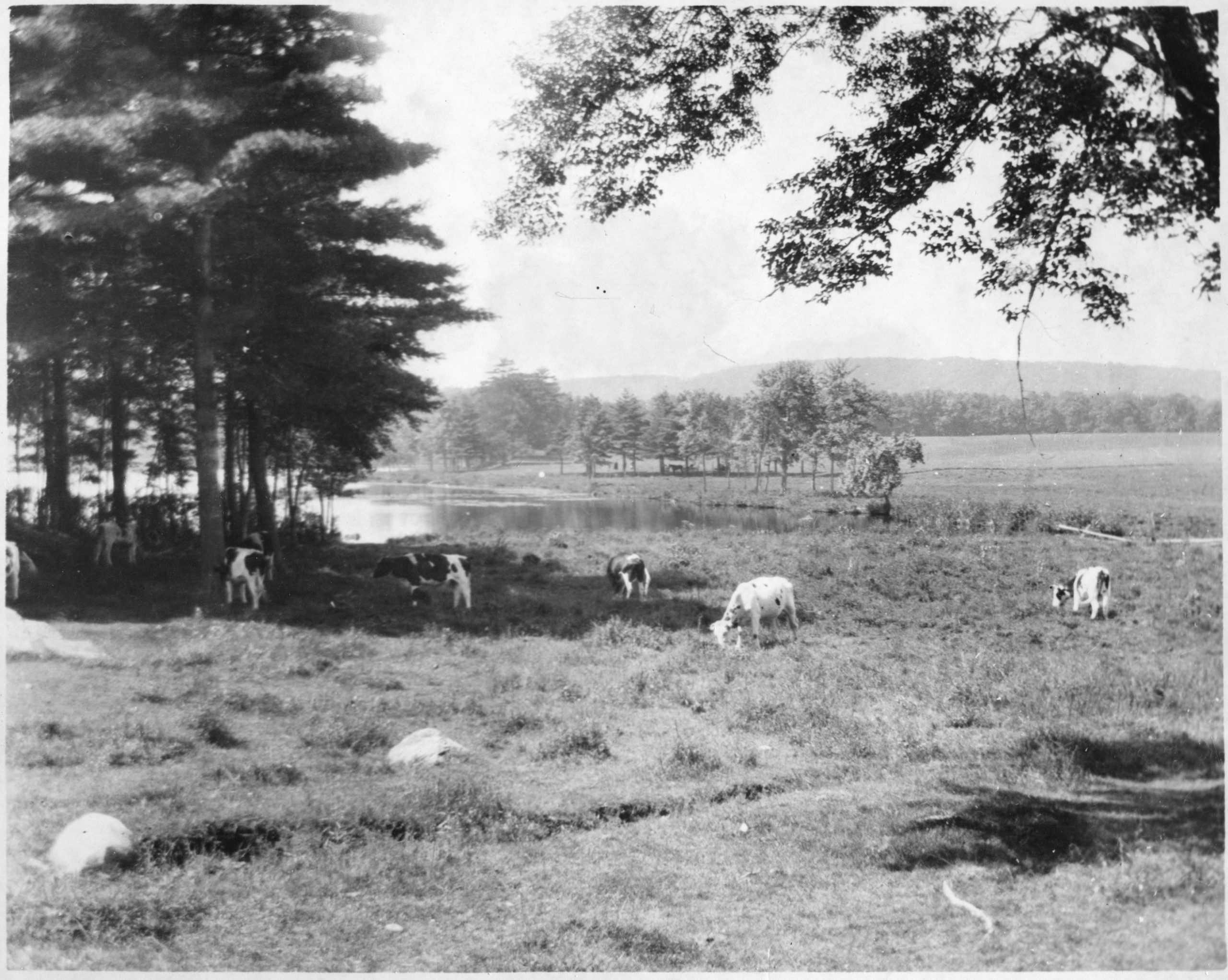

As we saw earlier in this series, while European settlers had no use for swamps—better to drain them to make farmland—they were crucial to the life of Native Americans in our area. Swamps provided connecting waterways that allowed Native Americans to move around and take advantage of seasonal food sources. They provided food, wood, water, and refuge. During King Philip’s War, Native Americans would burrow deep into swamps to find asylum, so several battles in the war took place in them.

The importance of swamps for Native Americans continued here in Westborough into the nineteenth century. Hoffman says that Jack Walkup—who owned a large amount of property adjoining Cedar Swamp and died at the age of 90 in 1978—claimed that when his grandmother was a child in the mid-nineteenth century, their family would put milk out on the doorstep for Indians who would emerge from the swamp during the winter to beg for food. An archaeological survey of the Cedar Swamp area by Hoffman revealed a small stone foundation along with clap pipe fragments, pieces of redware drinking mugs, glass, and nails from the mid-nineteenth century. Since no historic houses were ever recorded so deep in the swamp, the structure was most likely inhabited by Native Americans who harvested cedar as a cash crop to sell to townspeople to make shingles and clapboards. The shelter was most likely seasonal and sat unoccupied during the winter months. Hoffman contends that at the time he wrote his book in 1990, few cedar trees existed in the swamp anymore due to this logging, although Annie Reid in her Nature Notes series seems to indicate that by 2005 the Atlantic White Cedar had made a small recovery.

Rather than continue to tell a story that is of dubious value in learning about early Native American life in Westborough, more of a focus on the central role that the Cedar Swamp and other waterways in our town played in the lives of the people who lived here in town before European arrival would not only be more interesting, but more accurate. The Westborough Community Land Trust notes on its website that in 2003, Russ Cohen, “New England’s premier wild edible plant expert,” led a walk along the edges of Cedar Swamp. During his program, he identified an extraordinarily long list of edible plants, including choke cherry, day lily, dandelions, arugula, crabapple, acorns, and many others. No doubt, the Native Americans who lived and visited this area were well-aware of these edible plants and regularly gathered them for consumption.

A program that involves a visit to Cedar Swamp like the one conducted by Cohen—along with a discussion of the Hobomak who embodies the spirit of the swamp by bestowing fertility but also potential harm on those who encounter it—would be far more educational—and fun!—for third graders than listening to what is essentially an Indian princess story full of stereotypes. Afterall, “Nipmuc,” literally means, “People of the Fresh Water Lake,” so a discussion of why water is so central to their identity and existence is crucial to understanding them as people.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

- People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts by Curtiss R. Hoffman.

- “A Legend of the Hobamok” by Horace Maynard, in Horae Collegianae (August 1838). 308-319.

- Indian Names: Of Places in Worcester County Massachusetts by Lincoln N. Kinnicutt.

- The Hundredth Town, Glimpses of Life in Westborough, 1717-1817 by Harriette Merrifield Forbes. Online edition.

- “Westborough’s Atlantic White Cedar” by Annie Reid in Nature Notes.

- “South Cedar Swamp” on Westborough Community Land Trust website.

Click here to go to the next essay in the series, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough”

* * *

Nature Notes

Christmas is fast approaching, so many of us are decking out our living spaces with holiday decorations as we settle in for winter. Some of us look to bring natural items into our homes—Christmas trees, holly, sprigs of evergreens—to lighten up our interiors and remind us that a budding spring is in our future. We may even find Oriental bittersweet or American bittersweet with their bright red berries to add to our wreaths.

But alas, as Annie Reid points out in one of her December Nature Notes, the former berry has a bittersweet relationship to our environment, as it is an invasive species. Learn more about the difference between these two plants and about other natural phenomena in and around Westborough at this time of year in her December list of nature articles.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.