Special Edition: Westborough Center Updates

This summer has been busy in the Westborough Center with lots of big projects coming together all at once. Many of these developments will improve access to Westborough’s deep historical collections and will ensure that they can be enjoyed for years to come. Here is a summary of all these exciting happenings, which you can read about in more detail below:

- The Digitization of Two Important Collections

- Vault, a New Lockbox for Digital Files

- A New, and Significant, Ebenezer Parkman Publication

- The Processing of the Kristina Nilson Allen Papers

- A New Exhibit on the State Reform School for Boys

- An Upcoming Exhibit on the 1774 March to Worcester

- Nature Notes for August

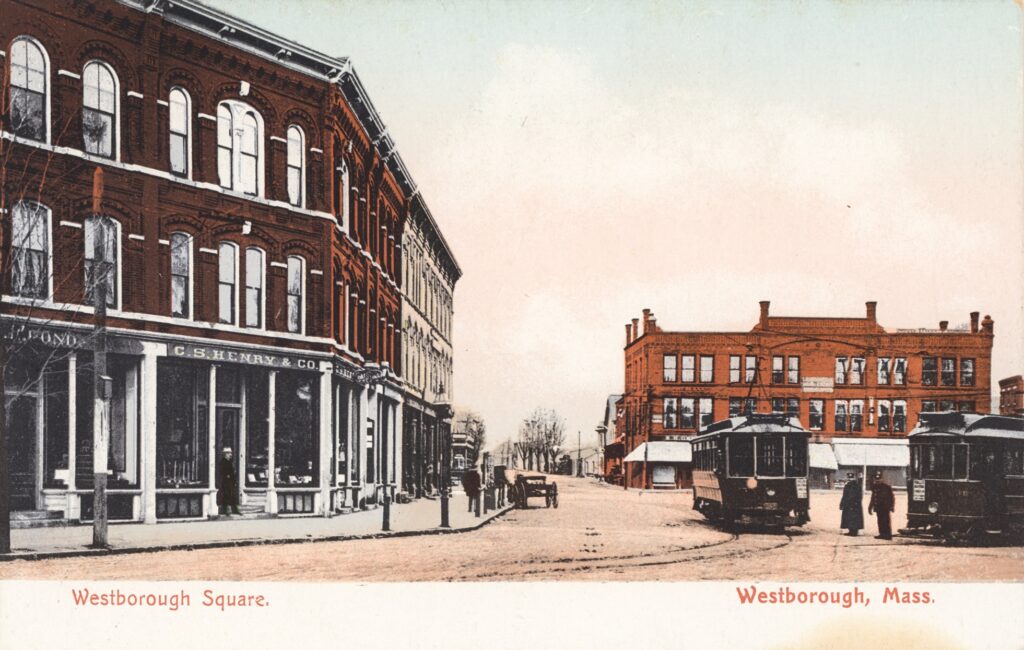

The Digitization of Two Important Collections

One of the Westborough Center’s most important collections is the Historical Photographs of Westborough Collection (LH.011). These photographs document Westborough’s history in images going back to the mid-nineteenth century and up to the present.

After I first took the position of Local History Librarian in 2015, I made a concerted effort to digitize this collection and progressively add the images I scanned to the Westborough Digital Repository. Over the years, a few interns also helped with this digitization. But the collection is massive—over 1,800 photographs—and with our combined efforts, we only managed to digitize about a third of the collection. (Needless to say, scanning single photographs over and over again entails drudgery, plus the tedious task of assigning metadata [the descriptive information that allows the photographs to be searchable] to each image. So excuses to work on “more pressing” projects other than this one were always easy to find.)

But this spring we received some unexpected grant money through our association with the Community Webs program run by the Internet Archive. We decided to use this money to finish off digitizing both the historical photograph collection and the Historical Postcards of Westborough Collection (LH.036). (By the way, if you are not already familiar with the Internet Archive, go check out its website now! You can spend hours searching and accessing all kinds of books, movies, television shows, audio recordings, even old video games!)

After I prepped the photographs and postcards for digitization, we sent them out to a private vendor to scan, and then I spent much of the summer adding metadata to each image. Taken together, the Historical Photographs and Historical Postcard collections comprise well over 2,100 images, and they are now all available online in the Digital Repository: Photographs and Postcards.

Vault, a New Lockbox for Digital Files

Okay, once all of these images are digitized, how do we preserve these digital files and ensure that they suddenly do not disappear? A lot of money and effort went into digitizing the above two image collections, not to mention all the items from other collections already in the Digital Repository, so saving them for posterity is imperative. Perfect timing! Once again Community Webs and the Internet Archive comes to the rescue with their brand new service, Vault.

Digital files are great for making content available when you want, wherever you want. But they are also extremely volatile. Think of all the times that a digital storage format you used, such as floppy disks, became obsolete because the machines needed to read them are no longer being made. Or the times when you mistakenly deleted something by hitting the wrong button. As a storage format, print is much more stable than digital, which is one reason why we do not throw away any print materials from the Westborough archives after we digitize them. Print and similar media formats are much better positioned to survive for long periods of time than digital files: think about how many books and manuscripts have survived hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

Just as I was preparing the photograph and postcard collections to send out for digitization, Community Webs announced that it was offering its members free digital storage through its new Vault service. Before this time, I relied on the principle of LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe) for preservation. I saved files on multiple computers and on separate disc drives, including one that I kept in my own home just in case the library met with some kind of disaster. Needless to say, my piecemeal digital preservation system was cumbersome, if not precarious, with the challenge of keeping all of these storage areas up to date.

With Vault, I can upload any file I want to save indefinitely into this storage service and be confident that we will always have access to it. Now the Internet Archive has the job of maintaining the integrity of this uploaded file by employing multiple storage facilities across the country that are constantly and automatically backed up. I have already uploaded all of the files in the Digital Repository, including the two image collections we just digitized. After nine years of worrying about digital preservation, I can now sleep just a little bit better at night!

Vault is the most important development at the Westborough Center that you will never feel or experience directly. But it is a crucial, game-changing tool that will reap benefits for our library for years to come. And did you catch that this service is entirely FREE for our library?! Go Internet Archive!

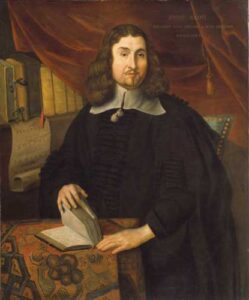

(American Antiquarian Society)

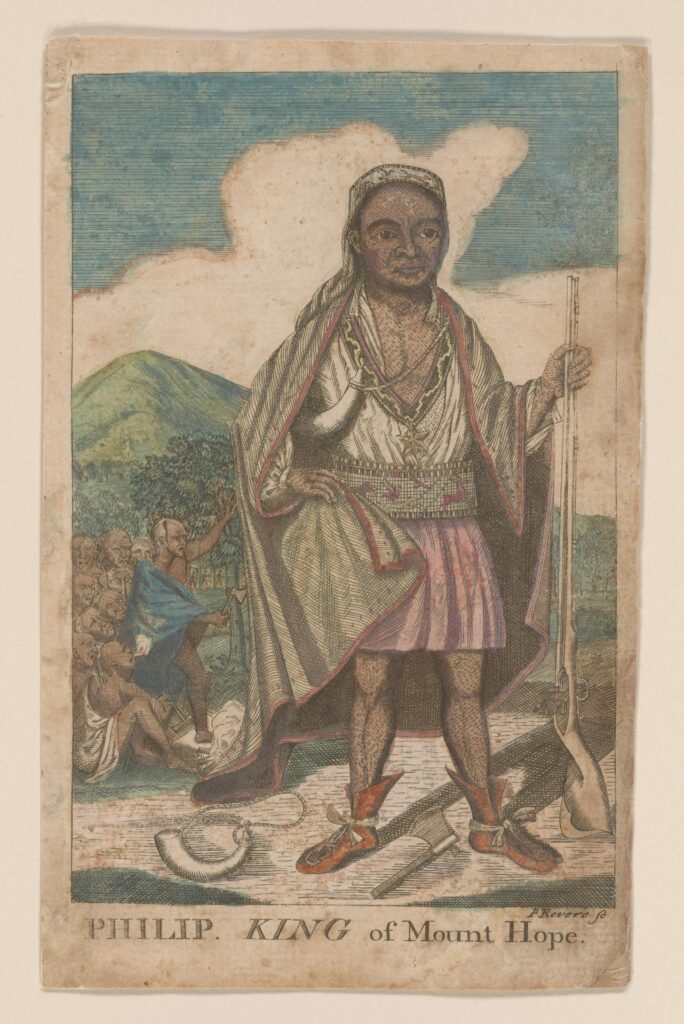

A New, and Significant, Ebenezer Parkman Publication

Regular readers of this newsletter should already be familiar with the Westborough Public Library’s Ebenezer Parkman Project, a digital humanities project that makes the diary of Rev. Ebenezer Parkman (Westborough’s first minister, who began his position in 1724), his other writings, and related documents from the town available and searchable online. The project is a joint effort with two other scholars besides myself: Dr. James Cooper, formerly the director of New England’s Hidden Histories, and Prof. Ross Beales, Jr., who provided all the transcriptions, content, and scholarship for the website. This project marked the first time that the entire extant Parkman diary was publicly made available.

But, like the issue of digital preservation above, the devilish problem of sustainability continued to dog me: our library is not in the publishing business, so what will happen to this project when the inevitable time comes when I leave the library or retire? Would the person who succeeds me be able to maintain the website, and if so, the person after that?

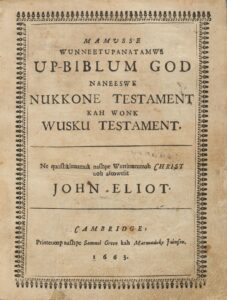

I am thrilled to announce that the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, which has a thriving publishing program centered on making important historical manuscripts and documents available to researchers and the public, has just published the first installment of Ebenezer Parkman’s World, basically, a more formal publication of the Ebenezer Parkman Project. New content will be added over time, so that this publication will eventually replicate all of the material that is currently on the Ebenezer Parkman Project website and more. Currently, Ebenezer Parkman’s Diary, Church Records, Sermons, and Relations of Faith and Confessions of Sins are all available. Future installments will include contextual documents from the town of Westborough that illustrate the people and places who appear in Parkman’s diary and existed during the time that he did, up until he died in 1782.

As co-directors of this project, we have often mused whether Westborough is the most well-documented colonial town in all of New England, given Parkman’s extensive diary and writings and our town’s near complete collection of historical records. Now, after working on this publication with the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, we wonder whether Westborough is the most well-documented colonial town in the entire country. That we can even ask this question in all seriousness shows how important this material is for the history of the United States.

The Processing of the Kristina Nilson Allen Papers

Anyone familiar with Westborough history knows Kris Allen, who in 1984 wrote the definitive history of Westborough, On the Beaten Path: Westborough, Massachusetts, and who today continues to be a historical force here in town. Over the past several years, Kris has been cleaning out her historical files and donating the contents to the library.

This collection, the Kristina Nilson Allen Papers (LH.032), includes newspaper clippings, brochures, pamphlets, manuscripts, photographs, and other materials about Westborough history, as well as a manuscript copy of On the Beaten Path. Other items include “The Suppers of the Club” cookbook, “A Collection of Historical Articles” written by Helena Engberg for the Evangelical Congregational Church, gravestone rubbings, and Lyman School materials.

Now sitting next to the Reed Collection, which covers much of Westborough’s history in the early- and mid-twentieth century along with its earlier history, Kris’s collection fills in much of Westborough’s history in the later-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. I have recently processed Kris’s collection, so you can gain a better understanding of what is in it in the Finding Aid, which I will update as Kris continues to donate important historical materials to the library.

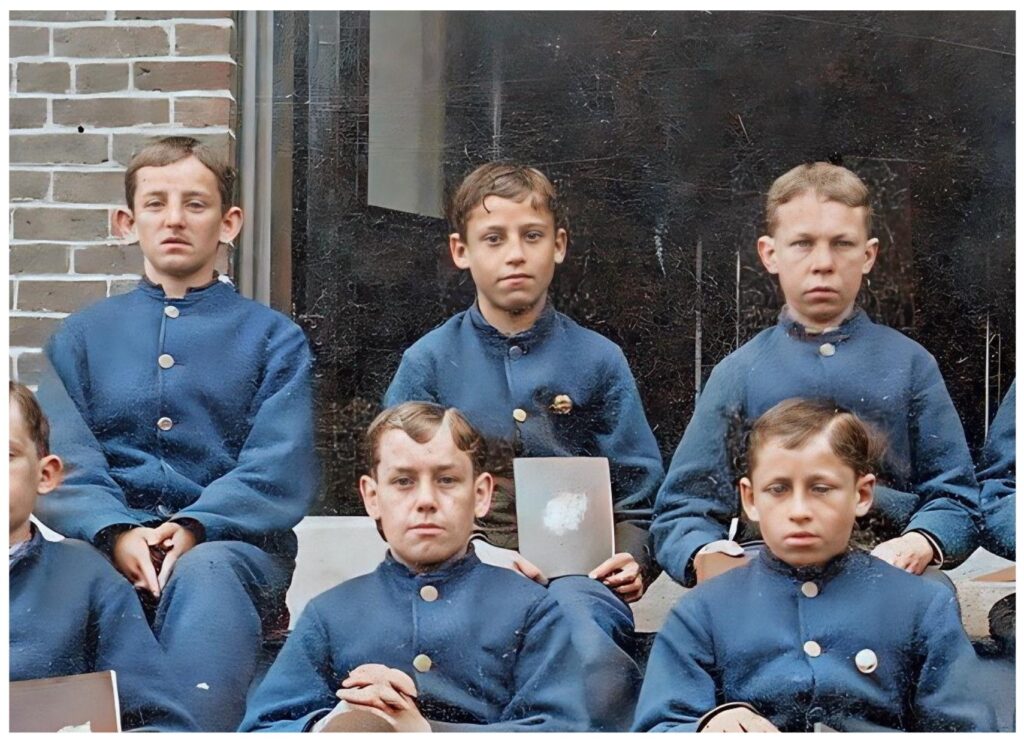

A New Exhibit on the State Reform School for Boys

When I first conceived of the Westborough Center for History and Culture, I envisioned a place where all kinds of people can not only research Westborough and its deep history, but also use this history to create new understandings about Westborough and share that knowledge with others. A new exhibit, “State Reform School for Boys, 1848-1884” curated by Jon Maynard, does just that!

Maynard, who has conducted deep and impressive research into the Reform School, the Lyman School, and the Westborough State Hospital, has colorized black-and-white photographs, so that, in his own words, “we get to see more of the humanity of those who lived and worked at the school.” You can experience this new way of seeing the Reform School in the display case right outside of the Westborough Center, which will be on view until the end of September.

An Upcoming Exhibit on the 1774 March to Worcester

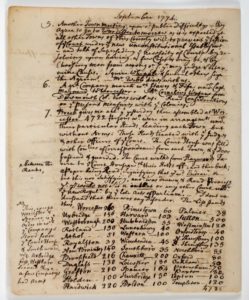

Believe it or not, the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States with the signing of the Declaration of Independence is fast coming up on July 4, 2026. But there were many significant events that led up to this momentous moment in history, and some of their anniversaries are already upon us. One of the most important of these events occurred in September, 250 years ago, when Westborough participated in the March to Worcester in 1774.

As a response to England’s passage of the “Intolerable Acts,” which restricted many of the civil rights that colonists had been enjoying up until that point, 4,622 militiamen from surrounding towns, including Westborough, marched into Worcester on September 6, 1774 to close down the Worcester County court. We only know this exact number of militiamen because Ebenezer Parkman recorded it in his diary (see the Parkman Project illustration above)! Many historians point to this moment as the true start of the American Revolution since the British never regained control of Worcester County. The event does not generally receive credit as such because what promised to be a violent uprising turned out to be a relatively peaceful transfer of power when the British quickly backed down after they learned about the colonists’ plans to block their army, which was poised to march from Boston to protect the Worcester court. Instead, the military action that occurred in Lexington and Concord created a much more exciting story to tell about our rebellion against England, and so better captured the public imagination.

Back in 2017 as part of Westborough’s 300th anniversary celebration, the library in conjunction with the Rotary Club of Westborough and the Westborough Historical Society held a Militia Training Day that recreated preparations for the historic march to Worcester. To help explain the details of this event, Leslie Leslie and I created an exhibit, which the library is now resurrecting to mark the march’s 250th anniversary.

The exhibit will be displayed in the library starting on Monday, August 26, 2024 and will run until the end of September. You can also learn more about the March to Worcester in the “exhibit catalog” I created for the Militia Day event: The Rebellion Begins: Westborough and the Start of the American Revolution, which is available here in the library.

* * *

And finally (whew!) a Westborough Pastimes newsletter would not be complete without . . .

Nature Notes

This past May when I visited my parents, who live in north-central Illinois, I was excited to experience the arrival of the cicadas. I remembered their emergence when I was a kid back in 1973. The sound of their roaring and periodic buzz filled the air, and the shells they shed clung to all the trees. (By the way, the 2024 confluence of the 13- and 17-year broods that was hyped in the media did not mean that people would experience more cicadas than usual in a given place. Rather, because the broods inhabit different geographical areas, they simply emerged in a wider area than usual, so more people got to experience them at the same time than usual.)

Alas, I did not hear or see any cicadas around my parents’ house. But, as Annie Reid in her Nature Notes observes, I can still enjoy the “sounds of summer” here in New England by listening to katydids. Learn all about them and then read about other natural phenomena to expect to see and experience in August here.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.