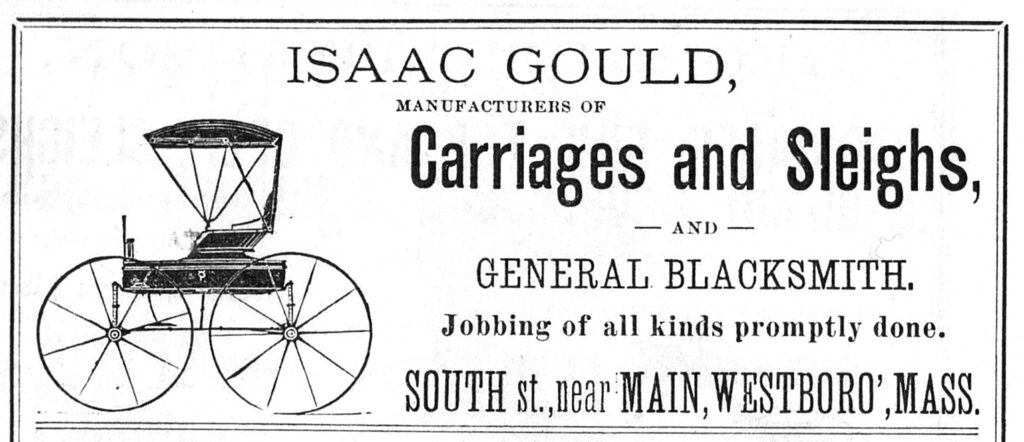

Westborough’s Blacksmiths

As a child, when my parents would take our family to craft fairs to sell their creations, I was given the freedom to wander among the various vendors on my own. Inevitably, I planted myself in front of a blacksmith, who demonstrated his technique while selling the metal items he made. I was fascinated by his ability to pound heated metal into the shape he wanted, and I sat for what seemed to be hours in the hope that he would throw me a cast-off nail that didn’t meet his standards. (One year, I finally summoned the courage to ask for one directly, and after he reluctantly fulfilled my request—he probably wanted me to buy one—I promptly lost and forgot about it. After all, what use was a faulty nail? Then again, what use was a handmade nail to a ten-year-old anyway?)

Blacksmiths were the automobile mechanics during the era of the horse. The diary of Rev. Ebenezer Parkman, Westborough’s first minister, is full of accounts of him dropping by the house of Cornelius Cook, the town blacksmith, to have horseshoes fit on his horse. Here is one example from March 1, 1737: “It had been very Icy and now by a snow upon the Ice and it was very Slippery and Troublesome riding. I rode to Mr. Cook’s to fix my Horse.” He writes as if he is having a mechanic put snow tires on his car for the winter!

Blacksmiths use charcoal to heat up metal to the point where it can be pounded and shaped into the desired product and design. Air needs to be forced into the charcoal fire to bring it to a high-enough temperature to make the metal pliable. In colonial days, such a task was accomplished with an enormous bellows made out of a couple deerskins or a whole bull’s hide. Generally, apprentices had the job of pumping the bellows and making sure that the fire remained hot enough.

Blacksmiths mainly provided the necessary service of making and mounting horseshoes to horses’ hooves to protect them from cracking while walking and working on rough terrain. But blacksmiths also provided other important products and tasks: making nails, latches, hinges, and other hardware; sharpening plow blades; and repairing chains. The account book of Joshua Mellen, a Westborough blacksmith and farmer who worked during the late eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries, records his activities between 1798 and 1802: shoeing horses and oxen, constructing or repairing fences, and making or fixing tools and farm equipment, such as scythes, shovels, and hoes. Like most people living at the time, Mellen took cash but also bartered for sugar, corn, liquor, and work as payment. Because their work and services were always in high demand, most blacksmiths did well economically.

The work of the blacksmith, however, was rarely inventive. We often celebrate craft for its ingenuity and its product’s close connection to the person making it, but craft usually involves some kind of repetitive labor as well. Trades before the Industrial Revolution required even more repetitiveness and less inventiveness when it comes to craft, since artisans had to meet a standard expectation of form and function in what they created for their customers. Horseshoes all had the same shape, even if the size needed adjustment for the individual horse. Nails were needed in the hundreds, if not thousands, which meant performing the same operation to make one nail over and over again.

The Cantankerous Cornelius Cook

Westborough’s most colorful blacksmith, at least judging by extant historical records, is Cornelius Cook. His son, Tom Cook, the Westborough’s notorious criminal, is better known in town lore, but his father also created plenty of trouble in town.

On August 22, 1727, Cook married Eunice Forbush, the daughter of Thomas Forbush (sometimes Forbes) who owned land where the Willows sits now on the corner of Lyman and East Main Streets. The marriage that day was their second attempt, since Parkman had ridden out to marry them the day before, but Cook could not provide a legal certificate. With a storm brewing, Parkman got impatient waiting for Cook to go and secure one, so he walked home. He left his horse and requested that Cook bring it back to his house, which he did. My guess is that Parkman was trying to kill two birds with one stone: marry the couple and get his horse serviced by Cook.

The marriage may have been forced, because the couple first had to confess to the sin of fornication. Having done so, Parkman married the couple and then baptized their son, Jonathan. In 1732, Cook’s father-in-law deeded a house and four acres of land to the couple, which also sat close to the intersection of Lyman and East Main. This house later became known as “the Plaster House,” given the bluish-hued plaster that covered it. The house was razed about a decade ago and was replaced with a modern house with a similar blue color.

In 1741, relations between Cook and Parkman and the Church erupted in animosity when Cook was charged with “undue Conduct and Language” (Westborough Church Records, June 28, 1741). On October 9, Cook was called to the Church to mount a “Declaration and Defence.” After doing so, the Church Council passed the following votes:

1. That the Church is not satisfyed with the Declaration made by Cornelius Cook, respecting his Guiltiness of the matter of Complaint made against him. Nem. Contrad.

2. That Cornelius Cook is, in the Judgment of the Church guilty of profane swearing; and Expects his Humiliation before he enjoy Special Privileges in the Church.

They concluded the meeting “with Prayer and the Blessing.”

Tensions between Cook and the Church continued. In January 26, 1743, Cook read a paper to the Church, “in which he hopd he was truly humble and sensible of his Sin in profane Swearing and prayd God and his people to forgive him etc.” After reading the paper, he was asked if he had anything to add, and

he told the Church (in Substance) that he doubted whether he was in a State of Grace at the Time of his taking Said Oath, and was in Doubt whether he ought to take it: but insisted that he was not guilty of taking it in the manner that the Church had understood it; was in no passion etc., but as well as he could in the fear of God – [As an?] act of worship: But as all his Family prayers, public attendances etc. were then profane, so was this also, and he could not judge it any otherwise etc. Upon which the Church debated and then passd were the following Votes —

- If the Confession offered by Cornelius Cook was satisfactory they were desird to manifest it by lifting up their hands.

To which No Hand was seen.

- If it was the Churchs mind to defer further proceeding with him by way of Censure for the present out of Tenderness and Compassion to him.

Almost a year and a half later, Cook finally “offerd a Confession of his Sin of profane Swearing and was restord.”

Still, Cook could not let the matter go. While in conversation with Parkman on September 11, 1744, “without any Sign of Provocation,” Cook “bitterly told me that he had been more abus’d by me, and by my wife and Children than ever he had been abus’d in All his Life.” The exchange clearly rattled Parkman, because he referred back to this admonishment again in his diary almost a year and a half later after Cook refused to shake hands with him after a bitter exchange between the two.

After this episode, tragedy began to fall on the Cook family. In August, 1746, “Fever and Flux” began to circulate and hit various families in town. Within three days, three of Cook’s eleven children (a twelfth seemed to have died at birth) died of the illness. By the middle of October, Parkman records that 24 children had died in town, with Cook’s Lydia being the first of them.

The hard times continued. On October 28, 1753, Cook appealed to the town for monetary support after learning that his two sons, Robert and Stephen, were imprisoned and tried for killing a Native American in Stockbridge. In 1760, Cook and his wife left Westborough and moved to Wrentham. Five years later, on December 4, 1765, Parkman received an update on the family: “We have not only Sorrowfull News of the Death of Mr. Cornelius Cook, once of this Town; but of the sad Condition of Several of his sons — That Daniel is hanged, and that Thomas has been condemned and has broke Jayl. It occasioned sorrowfull Reflections on Such vicious Lives!”

Westborough’s Last Blacksmiths

As late as 1918, two blacksmiths continued to practice in Westborough: Homer J. Pariseau on 8 Main Street and the “Estate” of George J. Jackson on 26 Cross Street. Helen Blois Schuhmann recalls as a child, probably around 1910, being fascinated with the work of George Jackson, and she provides, to my knowledge, a final account of a blacksmith in town:

I was born at 11 Ruggles St. and lived there the greatest part of my life. Jackson’s Blacksmith Shop was a big item to the youngsters in that area. Mr. Jackson lived at 16 Ruggles St. and the corner lot from there to 22 Cross Street was owned by him and his blacksmith shop founded on that area. Near the sidewalk was a large flat stone where metal tires were attached to the wooden wheels of wagons. When the truck from Bartlett Box Co. came to the shop with bundles of kindling, we knew that meant a busy time. The wooden wheel was placed on the stone, the metal tire was brought from the fire of kindling by two men with large gongs and quickly attached to the wooden wheel. Then water poured on from the hose quickly to be sure the hot metal could not burn any of the wooden wheel. That created a heavy smoke and suddenly that was the end of our watching. But one could go into the shop and watch the blacksmiths shoe horses. Mr. Jackson was very kind to us but each one was told where he or she could stand and observe. We obeyed his instructions for no one wanted to be deprived of an occasional visit to the blacksmith shop.

Works Cited

- Craft: An American History by Glenn Adamson.

- Colonial Living by Edwin Tunis.

- Joshua Mellen account book, 1798-1802 in Worlds of Change: Materials from 17th and 18th Century North America, Harvard Library.

- The Ebenezer Parkman Project: “Cornelius and Eunice (Forbes or Forbush) Cook.” and Westborough Church Records.

- The History of Westborough, Massachusetts by Heman Packard DeForest and Edward Craig Bates. Online edition.

- [Account of a blacksmith] by Helen Blois Schuhmann in the Kristina Nilson Allen Papers (LH..032).

* * *

The Historical Society Spring Bazaar

Don’t miss the Westborough Historical Society’s annual Spring Bazaar on Saturday, June 1, 2024 at the Westborough Historical Society, 13 Parkman Street. Discover unexpected treasures—antiques, jewelry, books—at bargain prices!

You can also drop off any donations at the Westborough Historical Society, 13 Parkman Street, from 1-3 p.m. on Wednesday, May 29; Thursday, May 30; or Friday, May 31.

* * *

Nature Notes

I just cleaned out my garage, but I kept the butterfly nets that my daughters used when we would walk down to the pond in our neighborhood to go “frogging,” even though both girls have grown up and left the house. After all, who knows if another set of young visitors may end up at our house someday and need a fun activity? But after reading Annie Reid’s “Songsters with Warts,” I now have to stop and ask myself: were we catching frogs or toads? Now, I may have to pull one of those nets off the rack and head to the pond to find out.

May, of course, is when nature suddenly springs to life. Learn more about what to expect to see this month in Reid’s Nature Notes for May.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.