This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Native Americans in Westborough History, Part I: Jack Straw

Six years ago, Westborough celebrated its 300th anniversary, an impressive milestone for a North American town. But this time span looks puny when put next to the 10,000+ years that Native Americans have lived on the land we now inhabit. In this context, I appear to be justified in devoting more than a full year to writing a series for this newsletter on Native Americans in Westborough history.

Even though I have been writing about the meeting of two cultures—Native American and European—with Westborough firmly in mind, the result repeatedly fell more on New England as a whole than on Westborough specifically. The difficulty in limiting such an inquiry to Westborough has to do with having to write a history where one of the cultures in question was primarily oral, so there are few records to consult. I addressed this problem at several points in the series. But Westborough is luckier than most New England towns, because Curtiss Hoffman, a New England archaeologist, devoted time and effort to researching Nipmuc life specifically in Westborough, which resulted in his book, People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts. Some of the people who had worked with him on his archaeological digs in town continue his work and education on this topic today.

But we are finally at the point in this series where we can squarely focus our full attention on Westborough, only now we are armed with what I hope is a new and broader context for understanding Native American life in New England and what happened to it after Europeans arrived here. This new context can help us build a better, more accurate, and more interesting way of understanding the continuity between the past and the present and the role of the Nipmucs in the broader history of our town.

Traditionally, when we address Native American history here in Westborough, we return to three stories: Jack Straw, the Legend of Hoccomocco, and the Rice Boys. We recount one or all of these stories, congratulate ourselves on checking off the Native American box of our town history, and then move on to the topics of original town settlers and the American Revolution. I, myself, have been guilty of treading this tired path many times. Now I hope that we are in a position to place these three stories within a better historical context than we have in the past—if not allow one or more of them to recede into the background—and begin to develop a more accurate and well-rounded means of addressing Native American history in Westborough.

This series has been a start in that process. Now let’s see what happens when we use the information in this series as a springboard into taking a closer look at how we have addressed Native American history up until now and what that history really tells us about Westborough, both before and after European arrival. The next few newsletters will conclude this long series by addressing each of the three traditional stories we tell about Native Americans here in Westborough.

Jack Straw and Native American Legacy in Westborough

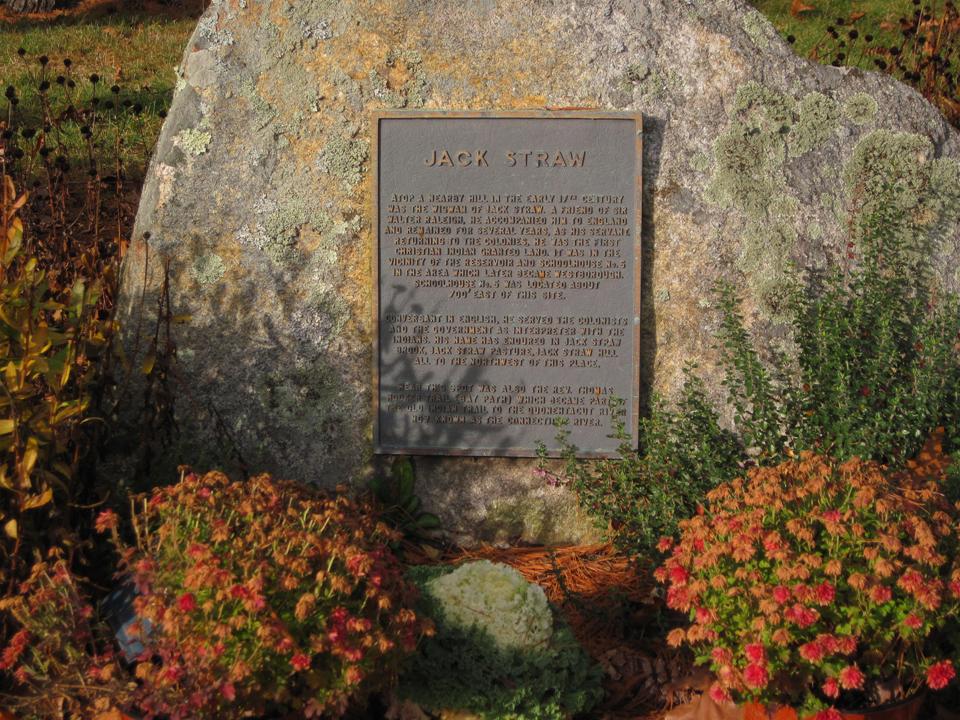

According to local tradition, Jack Straw’s Hill—now home to a housing division off of Bowman Street with a similar name—belonged to a Native American who was associated with Sir Walter Raleigh. In 1584, two Indians were taken from Virginia to England, where Raleigh presented them to Queen Elizabeth. One of them was named Manteo, and because he was reported to be the first Indian to be baptized a Christian, the Queen supposedly granted him 300 acres of land that would eventually become part of Westborough. Reference to an actual record of such a land grant never appears in any account of this story. How or why Manteo was tagged with the name Jack Straw, an English rebel who led the Peasant’s Revolt in England in 1381, is also never fully explained, nor why a Native American strongly associated with Virginia would be granted land far up north in Massachusetts.

Other stories claim that Jack Straw was a local Indian originally named Waunuckow, who was impressed into Raleigh’s service and then returned here. I cannot track down any reference to this specific Indian or story, however, beyond what Carroll M. Dearing wrote in the 1967 Commemorative Booklet for Westborough’s 250th anniversary.

A reference to Jack Straw also appears in Governor John Winthrop’s journal. In this account, a Native American named Jack Straw helped to negotiate a treaty between a Narragansett tribe from Rhode Island/southern Connecticut and the Massachusetts Bay Colony on April 4, 1631. In a 1901 journal article, William T. Forbes claims that “an historian” says that the delegation picked up Jack Straw and another Indian while traveling along the Old Connecticut Path to help with translation and the negotiation. (Forbes never names this historian.) If true, and this Jack Straw is the same person as Manteo, he would have been at least 67 years old, if not more. Winthrop’s diary entry, however, gives no indication about where Jack Straw came from and why he was a part of this delegation team. Forbes also cites references to “Jack Straw’s Hill” in early land grants, with the earliest one being in the 1670s, which gives land to the “relict and children of ‘Capt. Richard Beers, who lost his life in the country’s service, by the Indians, in Deerfield, in 1677’”—except that Beers died two years earlier in 1675 during King Philip’s War near Northfield, MA.

To muddy the waters of this history even more, Prof. Hoffman conducted a reconnaissance survey of Jackstraw Hill and could not find any evidence of prehistoric cultural material, nor find evidence that a Native American had ever occupied the hill. Even more, after learning all that we have about how Native American life tends to be highly socially oriented, a Native American living by himself during this time on top of a hill seems difficult to imagine, let alone one who came from a different part of the country and who had spent time in England. If Jack Straw had “turned Indian again” after having served Raleigh in England, as Winthrop claims, why would he now take up a secluded, sedentary life that falls well outside the semi-permanent villages that characterize Native American social life at the time? Not to mention that Native American life in our area gravitated towards water, not rocky hills.

Once we clear away all the doubt, we are not left with much of this story beyond the hill that bears the name of an English rebel from the Middle Ages, an Indian with that name joining a delegation to see Gov. Winthrop, and the land grants that refer to this geographical place more than forty years after that meeting. But based on what we have learned in this series and on skeptical rejection of details that cannot be verified, we also see an important theme emerge from this story: the erasure of Native Americans from the land in Westborough.

Indian geographical names emphasized a place’s natural, and hence sacred, function. Most of these names have since disappeared, save for a few like Hoccomocco Pond here in Westborough (more on this body of water in a future newsletter). Today, many of the land forms and streets that run through Westborough are instead named after the new settlers who moved in and founded our town. Even though Jackstraw Hill, Brook, and Path continue to bear the “name” of a Native American, his name is Anglicized and the man’s history is surrounded by ambiguity.

The story of Jack Straw also plays into the myth of the “last Indian” who lives by himself and represents the last vestige of Native American life before Europeans took total control of the land. As we have already seen in this series, some Native Americans reacted to European settlement by assimilating into this new culture and even took European names; others moved northwest, where they were better able to continue their traditional lifestyle. But Native Americans never completely disappeared from our area.

In his comprehensive survey of Native American tribes in Massachusetts in 1861, John M. Earle asserts that he could not find “one person of unmixed Indian blood.” Every time he researched the ancestral lineage of a Native American family, at least one member had intermarried with someone who was white or black. By the time Earle conducted his study, many of the Nipmucs who lived in the Hassanamisco reservation in Grafton (a former John Eliot praying town) had moved to Worcester and were mainly living in its African-American communities. Yet Earle also noted that most of the Native Americans he encountered remained proud of their heritage and worked hard to maintain it. In 1938 in the Westborough Chronotype, Charles H. Reed maintains that Native Americans “also married into the families of the white settlers and many of their descendants occupy high positions in society and the world.” Paralleling Earle, Reed goes on to say, “There are many now living in Westboro who are proud of the native blood that flows in their veins.”

Historical records are full of accounts of the “last Indian” only to have subsequent records continually demonstrate that Native Americans still exist and live in our local communities, albeit in much smaller numbers than they once enjoyed. Not surprisingly, this “mixing of blood” was also used as yet another sign of the disappearing Indian, when a “pure” Indian was not conveniently around to serve as proof of diminishing numbers and, consequently, the increasing irrelevance of Indigenous people. Native Americans today rightfully take umbrage at such a characterization.

The importance of land grants as a tool for displacing Native Americans from their land also appears in the story of Jack Straw. Now that we know the differing philosophies and epistemologies held by Native Americans and Europeans about property rights, we can make an argument that the summary of early land grants that appears merely as an Appendix at the end of Heman DeForest and Edward Bates’s The History of Westborough, Massachusetts (1891) should play a more central role in any discussion of Native Americans in Westborough history than a story about a lone Indian, perhaps the last one in Westborough, living on top of a hill that lacks detail and is full of inconsistencies.

Along with land grants, other mechanisms under which Indigenous lands were absorbed by the English merit a closer look. The Hassanamisco “Praying Town” reservation in Grafton—a mere four square-mile tract of land where in 1675 some of the Nipmucs were confined to live after King Phillips War—was further reduced over time starting in the 1730s to a measly three and one-half acres after the commission appointed to govern and oversee it sold or rented out much of the land over time to settlers. Captain Stephen Maynard of Westborough, a leader in the American Revolution, served as Treasurer of this commission after the war. At one point, Maynard was considered to be the richest man in Westborough until he eventually went broke and used $1,300 of the funds that had accumulated from the sale of this Nipmuc land to help pay his personal debt. Maynard eventually moved away from Westborough and never paid back the amount he took from this fund. During more flush times, he had also enslaved a small family—a man, woman, and daughter—before he sent all of them down South to be sold.

If we are to hold on to the story of Jack Straw and his supposed role in Westborough history, such a tale requires more nuance than we have given it in the past, if only to acknowledge the story’s participation in a double-edged erasure of Native American presence in Westborough: the erasure of present-day Native Americans based on the nineteenth-century myth of the disappearing Indian and over time the erasure of Indian place-names from the landscape in favor of European ones.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

- People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts by Curtiss R. Hoffman.

- The History of Westborough, Massachusetts by Heman Packard DeForest and Edward Craig Bates. Online edition.

- “Manteo and Jack Straw” by William T. Forbes, in Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (14:2, April 1901), 240-250.

- History of Worcester County, Massachusetts, with Biographical Sketches by William T. Forbes (1889: Vol II, p. 1336).

- Winthrop’s Journal: “History of New England,” 1630-1649, Vol. I by John Winthrop.

- “Native Americans Erroneously Called Indians” by Charles H. Reed in The Westborough Chronotype, September 16, 1938, p. 2.

- On the Beaten Path: Westborough, Massachusetts by Kristina Nilson Allen. Online edition.

- “They Were Here All Along: The Native American Presence in Lower-Central New England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries” by Baron, Donna Keith, et. al. in The William and Mary Quarterly (53:3, July 1996), 561-586.

- Report to the Governor and Council concerning the Indians of the Commonwealth, Under the Acts of April 16, 1859 by John Milton Earle.

- Ebenezer Parkman Project: Diary Themes: People: Native Americans.

- The Hundredth Town, Glimpses of Life in Westborough, 1717-1817 by Harriette Merrifield Forbes. Online edition.

- “Review of Behind the Frontier: Indians in Eighteenth-Century Eastern Massachusetts by Daniel R. Mandell” by Laurence M. Hauptman in Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Fall, 1998), pp. 141-143.

- “Stephen Maynard and His House” by Harriet Merrifield Forbes in Some Old Houses in Westborough, Mass. and Their Occupants, with an Account of the Parkman Diaries. Online edition.

Click here to go to the next essay in the series, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough”

* * *

Nature Notes

Over the last few weeks as I have entered my neighborhood in the evening, I have spotted two coyotes hanging out together on a front yard and what I believe is a fisher crossing the street and heading into the woods. Sure enough, both creatures show up in Annie Reid’s Nature Notes for November, so now I can learn all about them. What have you seen in your backyard lately?

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.