This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Native Americans in Westborough History, Part III: The Rice Boys, European Settlement, and War

In the mid-1680s, Chauncy Village was a thriving neighborhood of Marlborough. According to Harriette Merrifield Forbes, Edmund Rice and his brother Thomas, two of the first settlers in what became Westborough, built two garrison-houses. These houses were specifically designed to resist Indian attacks, which tells us something about the relations between the two groups at the time and how settlers had full knowledge that building houses on “unoccupied” land would not be taken well by the Nipmuc.

In 1702, the people who lived in the village filed a petition to establish a town separate from Marlborough and then did so again in 1716. Finally, the General Court granted the request in 1717, thus establishing Westborough as its own political entity. The abduction of the Rice Boys occurred in between the filing of these two petitions.

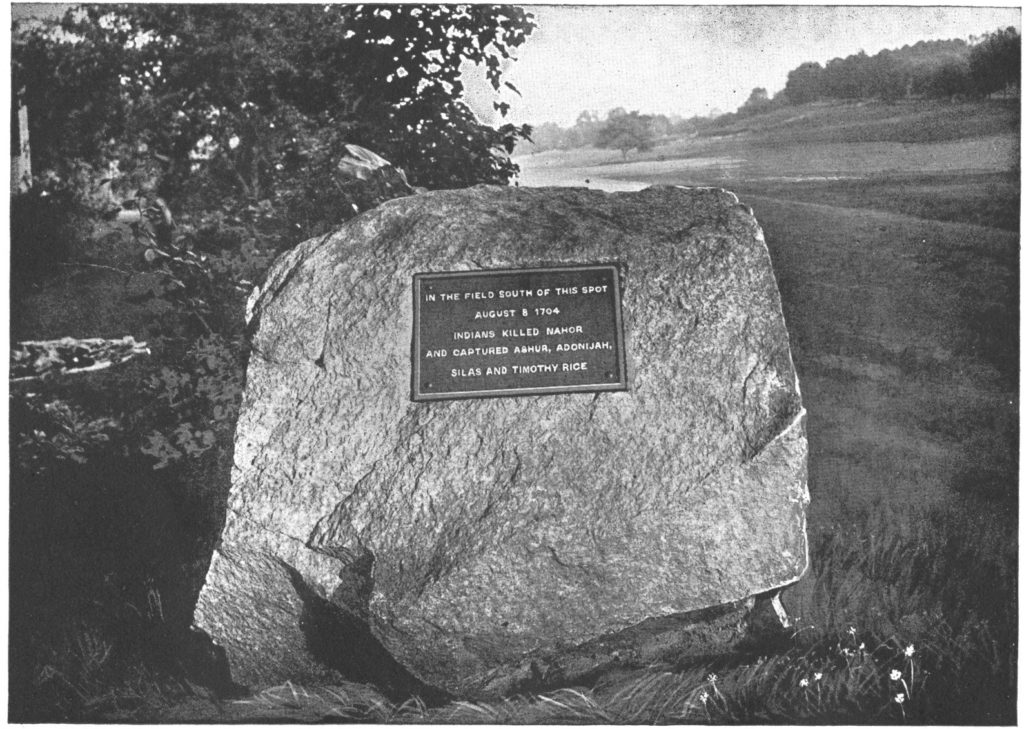

Unlike the other two Native American stories that we often treat as Westborough history—the Story of Jack Straw and the Legend of Hoccomocco—the “Story of the Rice Boys” offers firmer historical documentation. On August 8, 1704, members of the Rice family were spreading flax in the field where the Westborough High School is today when seven to ten Native Americans descended from the wooded hill and grabbed five boys from the work party. Before leaving the area, they killed the youngest boy, Nahor (age 5), by smashing his head in with a rock, and they took the other four—Asher (10), Adonijah (8), Silas (9), and Timothy (7)—with them north to what is now Canada. The rest of the family escaped to the safety of the house. Needless to say, the event was traumatic for both the family and the community.

Warfare

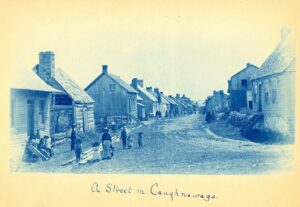

The abductors were members of the Caughnawaga Mohawks (now known as the Kahnawá:ke) who lived between fur trading posts in Quebec City (French) and Albany (British) and who were part of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Five Nation League. Not only were the Iroquois often at war with the Algonquins (the Nipmuc were members of the latter), but they had a trading relationship with the French, who were in competition with the English during the 17th and early 18th centuries for control of North America. The Caughnawaga often used both their diplomatic skills and the rivalry between the two European powers to their political and economic advantage.

We know from archaeological, linguistic, and folkloric evidence that Native Americans conducted war before European arrival, but their form of warfare was different from that of Europeans. War between Native Americans, at least in the Northeast, mostly involved random and periodic raids against enemy tribes and the taking of captives, who were then either adopted or enslaved. Characterized as more tit-for-tat engagements, this form of warfare rarely involved death and centered more on performing acts of bravery and on gaining the prestige that came with them. The “total war” that Europeans brought with them to North America horrified Native Americans. Europeans, on the other hand, were puzzled over why Native Americans did not take more lives during their wars. In their view, Native American warfare tended to draw out violent engagements over long periods of time rather than end them quickly with a decisive blow one way or another. (However, the names of many European conflicts during this time period seem to belie this point, such as The Eighty Years War, 1568-1648; The Thirty Years War, 1618–1648; The Seven Years War, 1756–1763, to name a few.)

The practice of taking captives and adopting them into a tribe became more important to Native Americans after European arrival. As disease decimated the Indigenous population, tribes, villages, and families had to recombine and reinvent themselves in order to survive. Even more, as the natural resources that Native Americans used to trade with the English—such as beaver—dwindled, competition among rival tribes for these resources increased. Maintaining a viable community became more and more difficult, to the point where, as historian Daniel K. Richter contends, “people were the scarcest resource of all in the Indians’ new world.” Richter goes on to argue that the Native people’s continual fight to rebuild their communities after their decimation by European arrival is one of the great American stories involving the triumph of the human spirit over adversity.

Was the raid that the Caughnawaga carried out that day in 1704 in Westborough a desperate attempt to strengthen the numbers of their tribe? This explanation may have been a factor, but the motivations behind the event are more complicated because it took place during and as part of Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713). I often argue that local history is necessarily embedded within a larger context, a context that at times can be global. In this case, the politics of European powers overseas and their common desire to take control of lands in North America had as much, if not more, to do with why the Rice boys were abducted and taken north.

European Wars

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, Native American tribes aligned with either the English or the French conducted raids along the contested and undefined border of New England and New France. Captives taken during these raids were often held for ransom from the European communities where they were taken. Others were adopted into the Native American tribe that took them. Attacking enemy settlements was a common feature of colonial warfare in the Atlantic Northeast. The English regularly employed this strategy against Native American villages as well. They burned down Indian homes, farm fields, and food stocks with the main goal of depriving Native Americans of shelter and starving them into submission. Needless to say, European writers at the time focused more on recounting settlement raids conducted by Native Americans than on those carried out by their own people.

Queen Anne’s War was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars that took place in North America. It was part of a broader war involving European nations struggling for power both over the Atlantic world and other parts of the globe. Outside of the United States—where the war was named after the queen who reigned in England at the time—historians refer to the conflict as part of the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1715), and it involved nearly every great European power at the time. As part of this war, French and Indigenous forces conducted raids deep into New England with the main aim of taking captives and securing ransoms for their return.

On February 29, 1704, fifty French along with 250 Abenaki and Caughnawaga Mohawks raided Deerfield, MA, where they killed 53 settlers and took 111 captives back with them up north. Most of the surviving children from this raid were adopted by the Mohawks. Some of the adults were ransomed or exchanged for prisoners taken by the English. In response to this event, the English sent 500 men in June up to Acadia (Nova Scotia), where they spent three days destroying towns, crops, dikes, and other settlements before returning back to Massachusetts. The abduction of the Rice boys on August 8 was either conducted in retaliation for the raid on Acadia or was part of a planned series of raids on the part of the French and the Caughnawaga.

After the abduction, Thomas Rice, one of the fathers of the boys, sold his house to raise money to ransom his sons back. After four years he was able to redeem his oldest son, Asher, who reportedly never recovered from the shock of the event and remained fearful of Native Americans throughout his life. The rest of the boys remained up north. Adonijah eventually married a French woman and settled into farming, while Silas and Timothy remained with the Caughnawaga and assimilated into their new way of life.

Continental Definitions and Ethnic Mixing

In her book, The Hundredth Town, Harriette M. Forbes tells an earlier story of how “an old Indian living in the forests around Westborough” named Graylock, and “who occasionally made raids on the settlers,” one day abducted Edmund Rice. As Graylock forced Rice down a trail, the captive managed to commandeer a heavy stick along the way and at an opportune time used it to kill Graylock. He then “ran back lightly over the fresh trail, and went on with his morning’s work.” Forbes goes on to speculate that this episode took place before 1704, since, by her account, the Rice Boys raid was conducted in revenge for the death of Graylock. Never mind that Graylock was most likely Nipmuc and that the raiders from far up north belonged to a rival group.

Forbes makes a common error here by thinking of Native Americans continentally rather than tribally. (As a side note, African-Americans also tend to be identified continentally and rarely by individual country when it comes to their ethnic origins.) In contrast, European Americans are mainly defined by distinct countries. My ethnic background may be a mixture of German, Scandinavian, Polish, and Italian (if my family heritage and DNA results are to be believed), but I have never been referred to as “European,” even though such a designation would more accurately describe the span of my family background across almost all of that small continent. Forbes’s assumption that a tribe over 300 miles away had any interest in avenging the killing of a Nipmuc Indian and member of the rival Algonquin tribe is just one manifestation of the tendency to conflate all Indians as being one and the same. How common is it to make similar assumptions that, say, Germans, Scandinavians, Polish, and Italians are all the same, or that someone in, say, Munich would have any interest in avenging a death in Milan?

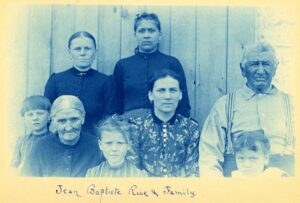

Colonial histories are full of accounts of settlers captured by Native Americans choosing to stay with their new families rather than returning to their biological ones. Conversely, stories of Native Americans who became a part of European society and then chose to escape or return to Indigenous society—even when they lived what was considered to be wealthy and educated lives in their European setting—are also numerous in the historical record. Contrary to usual assumptions, most people who were given a choice opted for the advantages that Indigenous lifestyles offered them. Many of those who assimilated into Native American life even rose to take prominent positions within their communities. Such was the case for Timothy Rice, who was adopted by the Caughnawaga chief and later as an adult became a sachem of the Six Nations of the Iroquois. In 1740, he returned to visit Westborough, and even though he recognized his childhood home, he could no longer speak English.

Today, due to the history of adopting European captives into their tribe, many of the Kahnawá:ke (Caughnawaga) have mixed ancestries, so they identify culturally as Mohawk yet have European surnames, including Rice.

Next month, we will finally conclude this long series on the meeting of two cultures in Westborough with a brief look at the status of the Nipmuc today and draw some conclusions by reflecting back on what we have learned.

Works Consulted:

- The Hundredth Town, Glimpses of Life in Westborough, 1717-1817 by Harriette Merrifield Forbes. Online edition.

- Two Indian Chiefs by Harriette M. Forbes, from the Proceedings of the Worcester Society of Antiquity, 1893 (LH.001: Native Americans).

- People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts by Curtiss R. Hoffman.

- The Story of the Rice Boys: Captured by the Indians, August 8, 1704 by Ebenezer Parkman.

- TSI NITIOHTÓN:NE OKÁ:RA: History of Kahnawá:ke: The Mohawk Council of Kahnawá:ke (website): http://www.kahnawake.com/.

- Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America by Daniel K. Richter.

- The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow.

- Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America by Pekka Hämäläinen.

- Native Americans of New England by Christoph Strobel.

Click here to go to the next essay in the series, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough”

* * *

Take the Nature Notes Quiz

We are in the middle of winter, so our inclination is to hibernate in our warm homes rather than head out into nature. Luckily, Annie Reid has created her annual Nature Notes Quiz for 2023 to give us something to do while we sit in front of a fire with our hot chocolate. And if you ace this quiz in short order, there are plenty of other quizzes to test yourself from her past Nature Notes for January.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.