Now is the Time to Grow: A Special Final Issue

Over ten years ago, I started organizing Westborough’s historical town documents and then became the Local History Librarian. The local history room I inherited was mainly organized like a library, not an archive, which meant that while it was easy to find books about Westborough history, there were scores of document and manuscript collections that remained hidden away because there was no organizational structure in place to know what we have and where it was stored. These historical records may as well have never existed, because no one really knew that they were there.

Given this situation, I developed three goals: 1) organize the important historical records held by both the library and the town to conform with standard archival practices; 2) implement new, mainly digital, collection tools, both to increase access to these historical collections and to continue collecting the important records that we ourselves create in our digital environment; and 3) use these new organizational structures and tools so that we can begin to practice local history in innovative ways that are more relevant to us now.

Let’s start with the first goal. I started in one corner of the essentially unorganized local history room and proceeded go around the room to create an inventory of everything that was stored in it. From there, I created discrete collections and assigned each of them a unique number that can be used to help researchers find them. I created finding aids for what I deemed to be the most important collections so that researchers can more easily identify individual items that are most relevant to their project. And then I put all this information into a searchable catalog. Now we know what we have, and people can better find the historical information they are seeking.

As for the second goal, I conducted several digitization projects and implemented digital tools, both to provide easy access to newly created digital images and to collect the digital records that we create today.

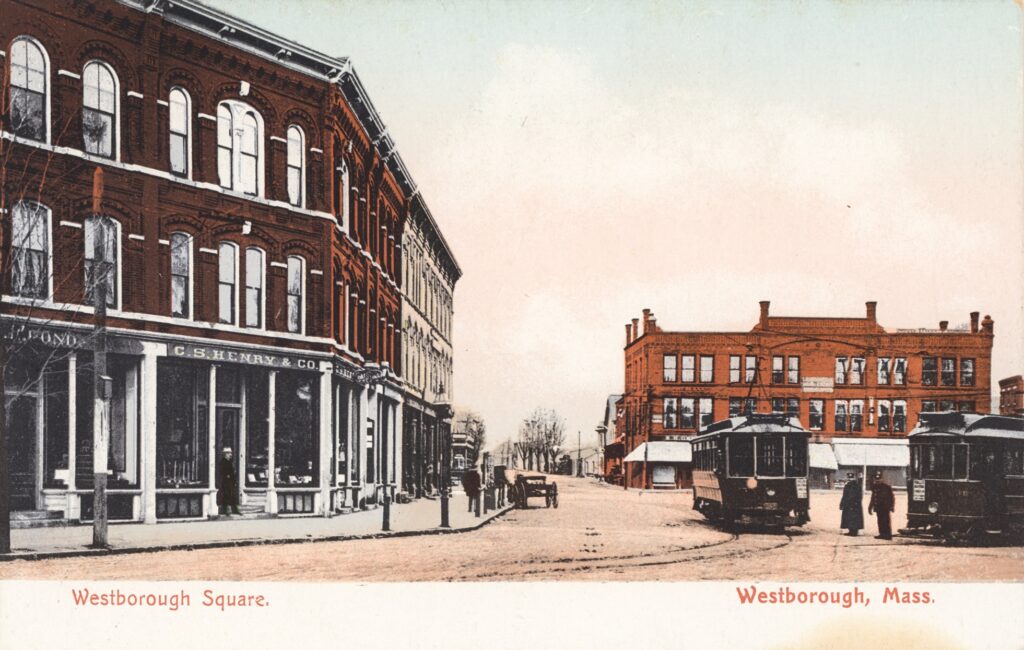

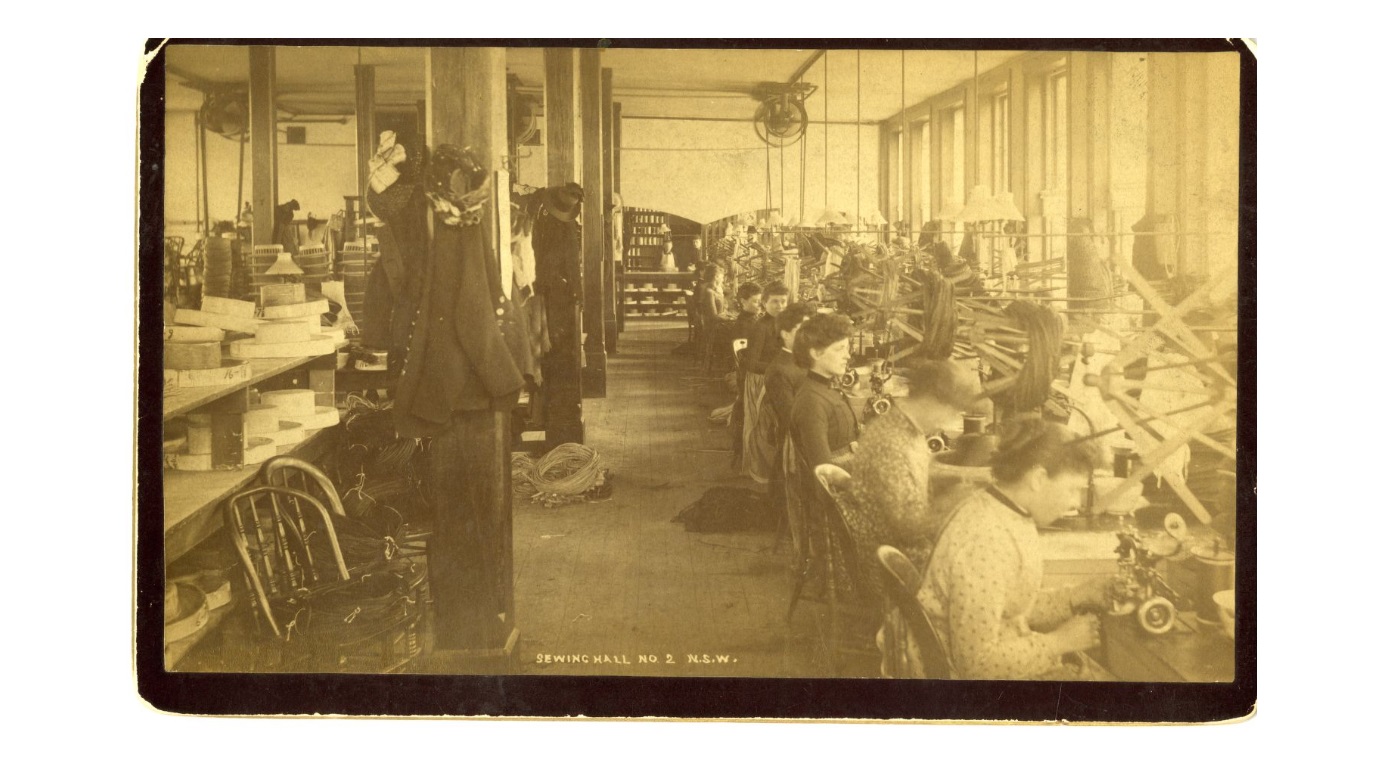

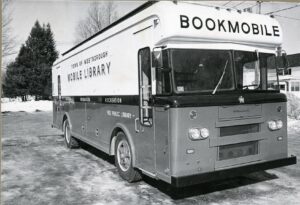

- I digitized many of the Town’s historical records with the help of the Digital Commonwealth. I also digitized important collections held by the Library, including the Historical Photographs Collection, the Historical Postcard Collection, as well as images from Reform/Lyman School and the State Hospital collections, among others. And then I implemented a Digital Repository for people to access all this content online.

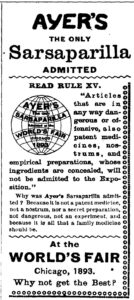

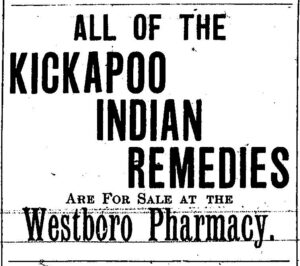

- I digitized our Historical Newspaper Collection that was only available in microfilm. Now researchers can access all this content on a computer in the library or at home and not have to rely on a clunky microfilm machine to view it.

- As founding members of the Internet Archive’s Community Webs program, which has given our library free access to and training on their Archive-It collection tool that continues to this day, I was able to collect web and social media sites and store them in Westborough on the Web: Archive-It, so that future researchers can gain insight into who we are as a town today.

- And the Internet Archive generously came through again to give us free storage in their brand-new Vault tool, so that I could save all the digital materials I have created over the years and be assured that they will remain safe and secure for as long as the Internet Archive exists. This behind-the-scenes tool may be our most important one, since it allows an archivist like me to sleep more soundly at night knowing that our ordinarily volatile digital media is safe and secure.

And finally, I tried to use these new tools to start developing new approaches to the practice of local history.

- I secured a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to conduct a Scanning Day, where residents in town could donate to the library images of historical records they own and that otherwise would remain hidden away in their houses.

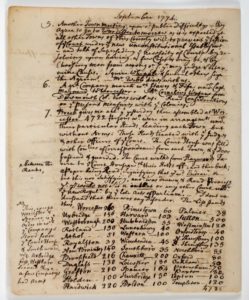

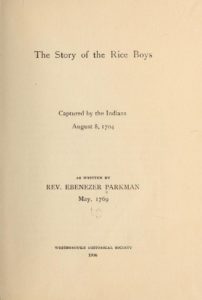

- I worked with Prof. Ross W. Beales, Jr. and Dr. James Cooper to create the Ebenezer Parkman Project, which brings together and makes available the vast corpus of Parkman’s writings along with town records to create what may be the most complete picture of a rural colonial town in all of the United States. This content is now formally being published by the Colonial Society of Massachusetts as Ebenezer Parkman’s World. Even more exciting developments connected to this project will be coming in the future.

- I created a Photographer-in-Residence program and selected Brandin Tumeinski to photograph Westborough residents over the course of one year (2018-2019) to add more contemporary images to our deep historical photograph holdings.

- I wrote this newsletter and created exhibits that attempted to place Westborough’s history in broader historical contexts, including the following blog series:

- And we rebranded the local history program as the Westborough Center for History and Culture to indicate the new kinds of work that can be done in our local history space.

In truth, these three goals will never go away: there always seems to be more collections to process, new digital tools to implement, and more innovative programming to create. But after ten years of work, the Westborough Center is finally in a solid and unique place to develop and define new ways to practice local history in an unprecedented way.

If you quickly review my list above, you will see a lot of “I” and not a lot of “we.” Now is the time to correct this imbalance and bring more people into researching, exploring, and sharing Westborough’s deep history using all these new resources. The Westborough Center is primed to grow and become a truly ground-breaking force in the field of local history, and the library is looking to you to help with this endeavor.

To this end, I am excited to announce that Dr. Tracey Graham, the Adult Services Librarian, will be taking over as point for the Local History collection, and I will be moving into a consulting role in the Westborough Center. We hope you will join us as we look for new ways to explore and understand the history and culture of our thriving community and to develop even deeper partnerships with other organizations in town that will work towards these ends.

Over the years, this newsletter, in essence, has been an extended argument about how local history can be a means of exploring and understanding both who we are as a town and who we are as individuals who live in that town. This new leadership structure will better facilitate my original dream for the Westborough Center: to be a place where people can research our town’s deep history, share knowledge about where we live with each other, and use this knowledge to create new ideas about who we can be as a community. Collaboration is key to achieving this vision, and I am looking forward to becoming a collaborator with the Westborough Center—just like you.

No doubt, Tracey will bring her own ideas about how the Westborough Center can and should grow in the future. I can’t wait to become a part of this new growth opportunity, and I hope you will join me in seeing what we can accomplish when we work together to reflect on what Westborough was in the past, what it is in the present, and what it could become in the future. Because when we do this work, we become more engaged in our community and more fulfilled as human beings.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Do you want to receive future updates on Westborough Center activities? Then subscribe to notices by e-mail and have them delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

* * *

Upcoming Westborough Historical Society Programs

Wednesday, November 13, “Chalk It up to History” Tour – Families are encouraged to discover vintage homes of famous people in Westborough, as you tour Parkman, Grove, and Church Streets with Westborough historian and author Kris Allen. Free of charge. This program is part of Kindness Week Events with Westborough Connects. Meet at the William Sibley House, 13 Parkman Street, at 3:45 pm

Saturday, November 16, “Celebrating Veterans” Open House – Join us at the William Sibley House for a special exhibit of military artifacts through the ages. Free of charge. Meet at the William Sibley House, 13 Parkman Street, 2 to 4 pm

* * *

Nature Notes

One of the many joys I have had in writing this newsletter has been working with Annie Reid and Garry Kessler on promoting their Nature Notes columns. Before the Westborough Center was even a concept, Annie and Garry have been contributing to a better understanding of Westborough through the nature that surrounds us. They embody the spirit of what I hope the Westborough Center can become, and even though I will no longer be promoting their work in this newsletter, I look forward to continued collaboration and interaction with them.

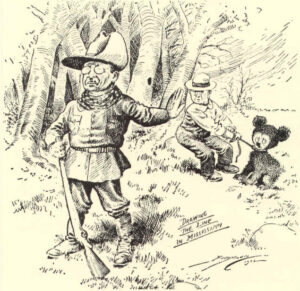

So what better way to end this newsletter than to read one of Annie’s favorite column on bears. I love bears! Teddy bears have long been a staple toy for children, including me. But my relationship with them became even deeper when I became old enough to learn about the history of their “invention” when Teddy Roosevelt appeared in a cartoon that depicted his refusal to shoot a bear cub that his assistants had tied to a tree for him to shoot after a long and unsuccessful day of hunting. From that point forward, my connection to my teddy bears deepened because of history.

And, as usual, you can read and learn more about Westborough’s natural world during this time of year in Annie’s Nature Notes for November.

* * *

Do you want to receive future updates on Westborough Center activities? Then subscribe to notices by e-mail and have them delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.

On Monday, January 8, 2024 at 6:30 p.m. at the Westborough Library, the Westborough Historical Society will present “Anything Goes—America During the Jazz Age: ‘The Roaring Twenties’” with historian Christopher Daley.

On Monday, January 8, 2024 at 6:30 p.m. at the Westborough Library, the Westborough Historical Society will present “Anything Goes—America During the Jazz Age: ‘The Roaring Twenties’” with historian Christopher Daley.