Timelines

1492, 1620, 1776 . . .

These years and their significance were drilled into our heads in elementary school history classes (respectively, the years when Columbus set off to “discover America,” the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts, and the Declaration of Independence was signed). They, and others like them, are so common in our minds that we rarely give them much thought beyond their seemingly innate connection to the historical event that they represent.

For as long as I remember I have been fascinated by history. The museums and historic sites I visited, the books I read, and the movies set in historical time periods I watched were all reminders that people used to live life very differently than I do. They dressed differently. They used different kinds of transportation. They generally worked different kinds of jobs. They thought differently. And they held different attitudes towards life. How strange that if either of us landed in the other’s time period that we would feel totally out of place! And what does this insight mean as we head into the future? How different will that time be from what I think is “normal” now?

But my real understanding of history did not begin until I made the conscious decision not only to note the dates of when events happened, but to fix those date in my mind and place them in relation to all the other dates rolling around in my head. Sounds pretty basic, right? Don’t we all know to do that when we think about history? Maybe, maybe not. I’m not exactly sure when I made this commitment to myself somewhere along my personal timeline, but I do know that it was embarrassingly later in my life than I would like to admit. Nonetheless my decision was a game-changer! As I assembled dates into a mental timeline, my understanding of history deepened to a degree that I did not anticipate.

As way of example, let’s historicize our practice of thinking about historical timelines. I am currently reading A World Lit Only By Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance, Portrait of an Age by William Manchester about the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Manchester contends that most people living in medieval Europe had no awareness of time, at least not in the way that we do in the twenty-first century. Not only could they not tell us the time of day (they had no clocks), but they could not tell us what century they were living in, because it just did not matter to them. As Manchester points out, the difference between life in 1791 and 1991 is huge, but everyday life in 791 and 991 was essentially the same. In the Middle Ages, one generation blurred into the next one, yearly harvest cycles and religious holidays circled round and round, and people’s lives followed a set path marked mostly by church rituals (baptism, marriage, funerals).

And now we can place this difference on a timeline that gives us a deeper understanding of how people lived and thought between and around the years 791 and 991 when compared to two hundred years ago or today. We may also ponder the advantages of living in an era when time as we know it is not even a concept, especially as we rush out the door to make it on time to work or to our daughter’s soccer practice.

Now when you learn about history, I encourage you to pay close attention to dates and place them along your own mental timeline of other historical dates that you know. I guarantee that a richer tapestry of history and the human experience will begin to emerge.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Suggested Reading:

- A World Lit Only By Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance, Portrait of an Age by William Manchester

- Millennium: From Religion to Revolution: How Civilization Has Changed Over a Thousand Years by Ian Mortimer

- Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari

- Millennium, Year By Year

* * *

Here are some years when important events took place in the history of Westborough. Can you name the event associated with each year? Click on the link for hints or to learn more.

* * *

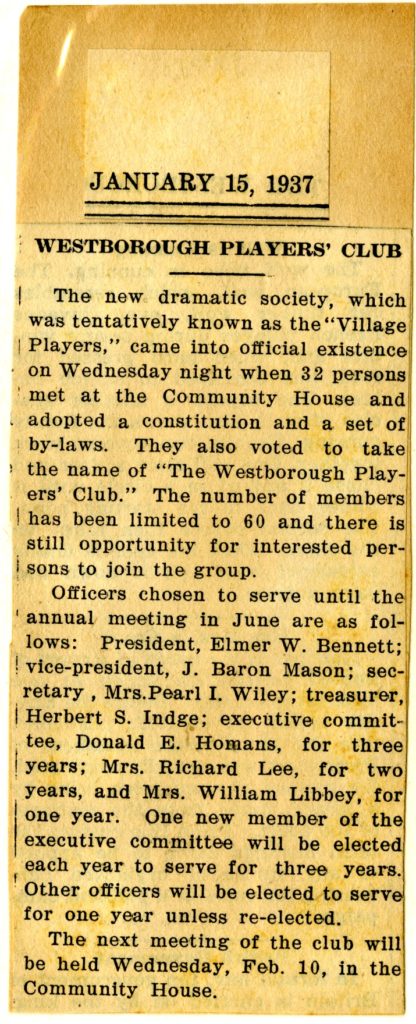

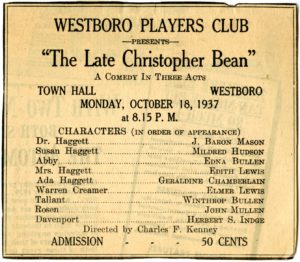

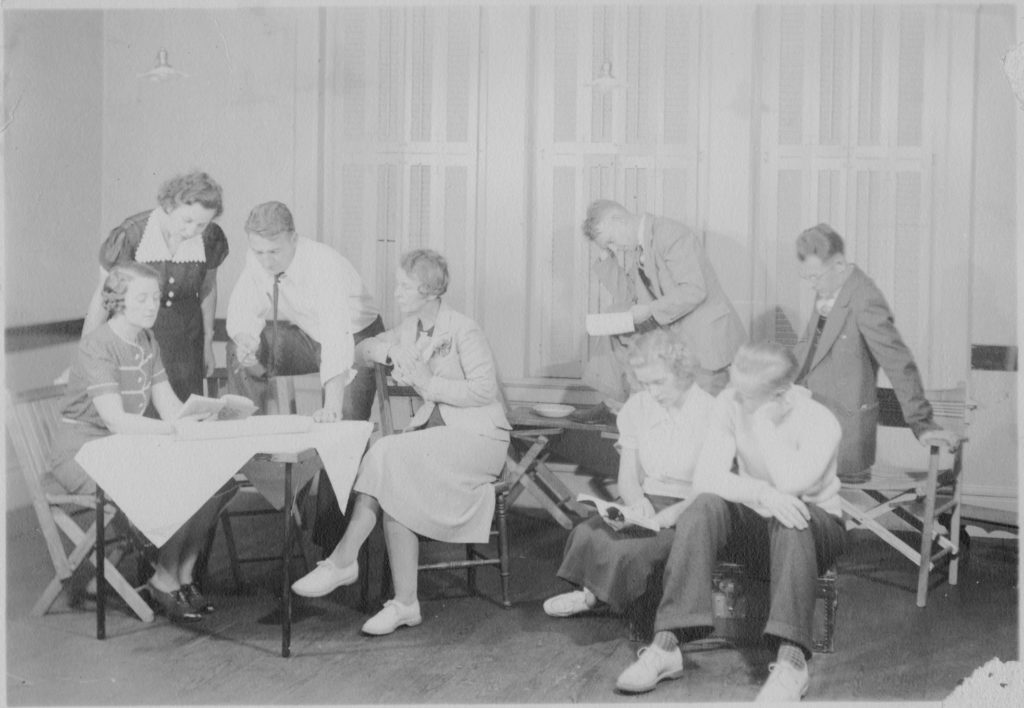

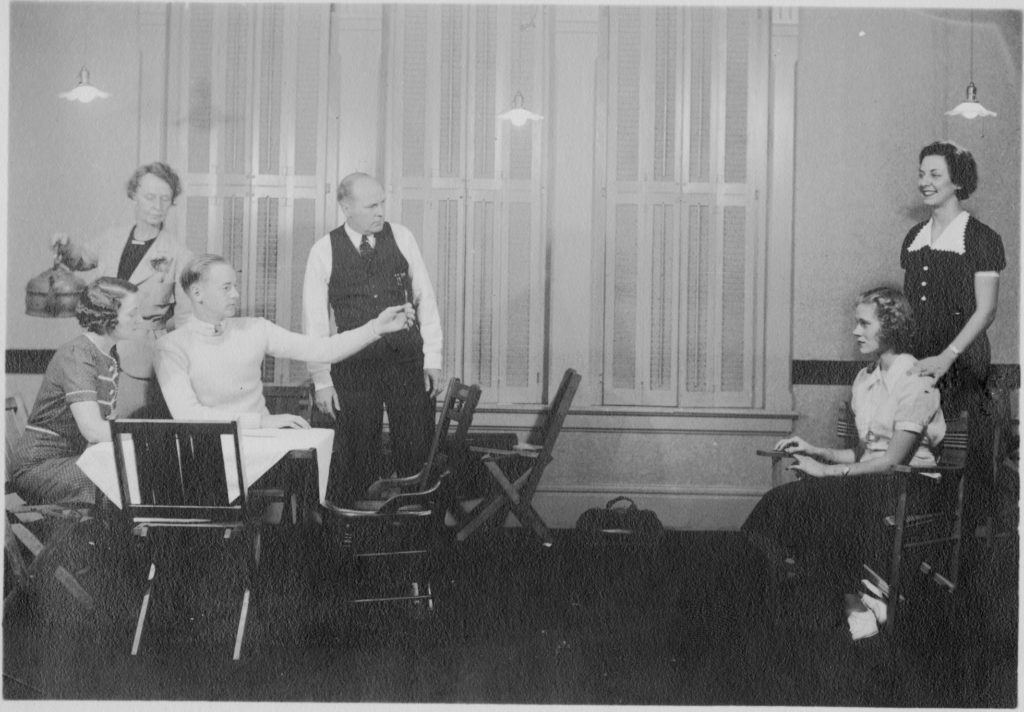

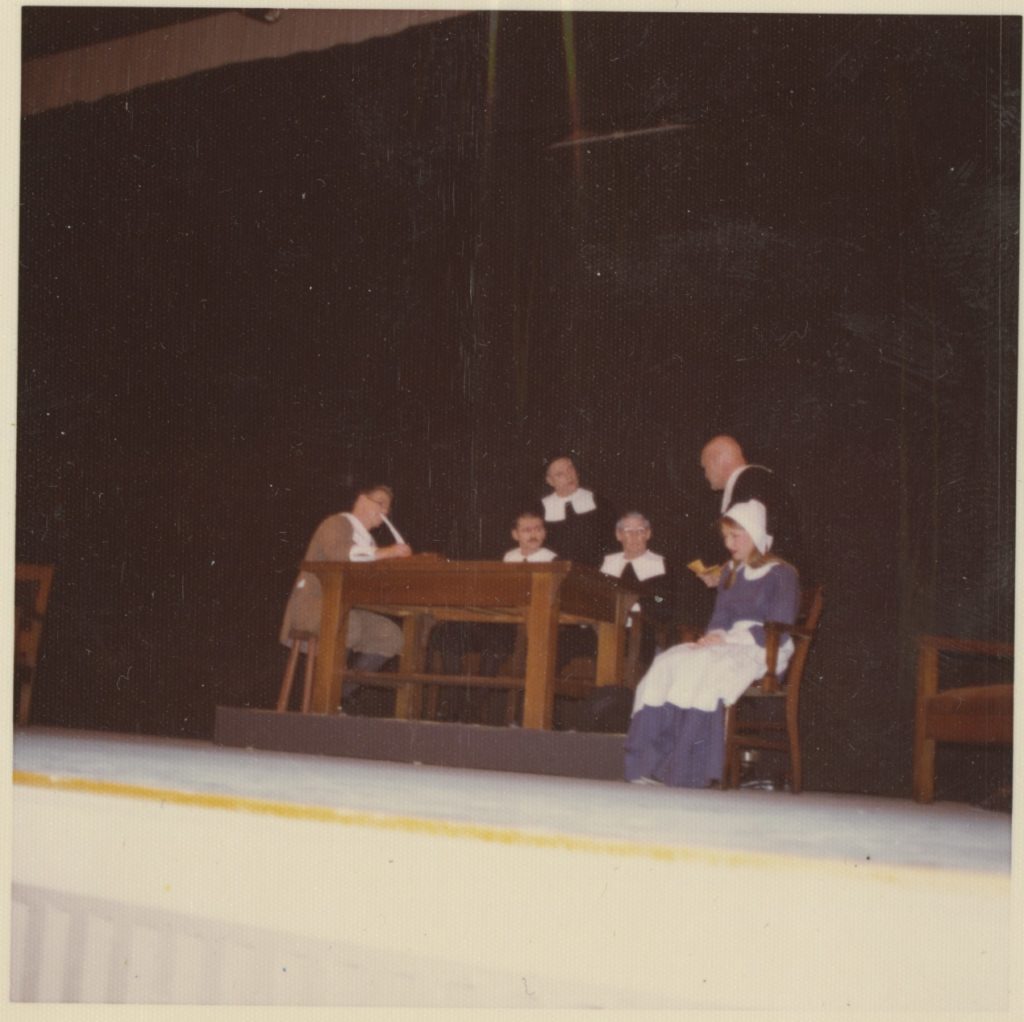

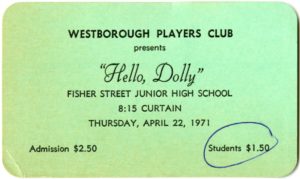

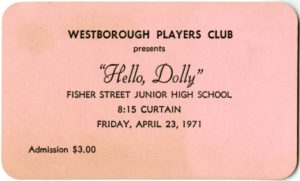

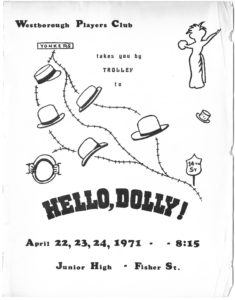

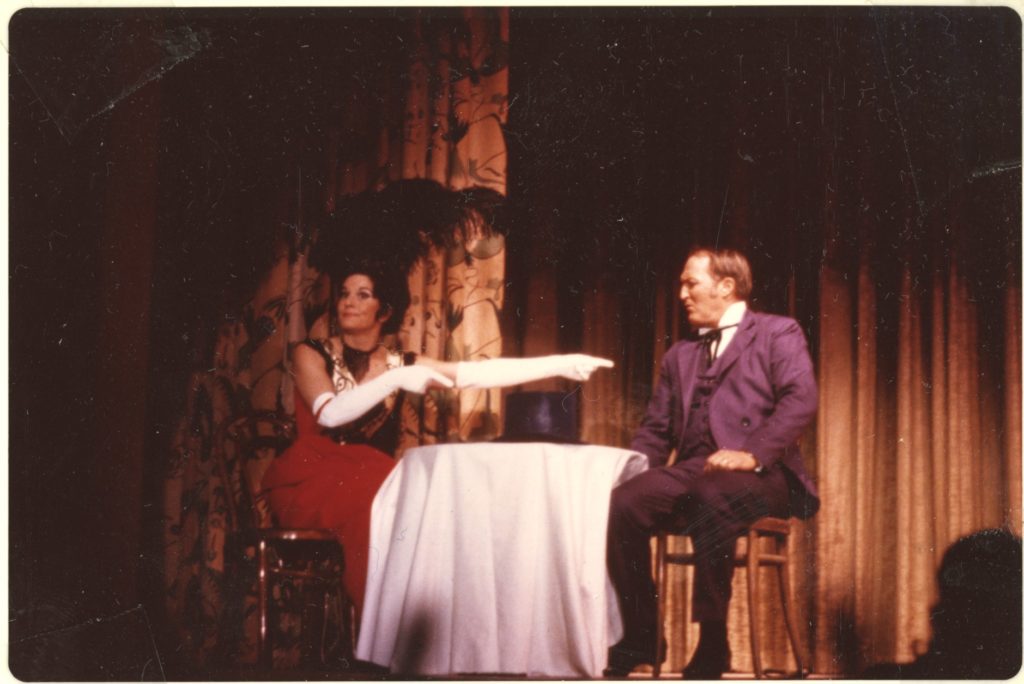

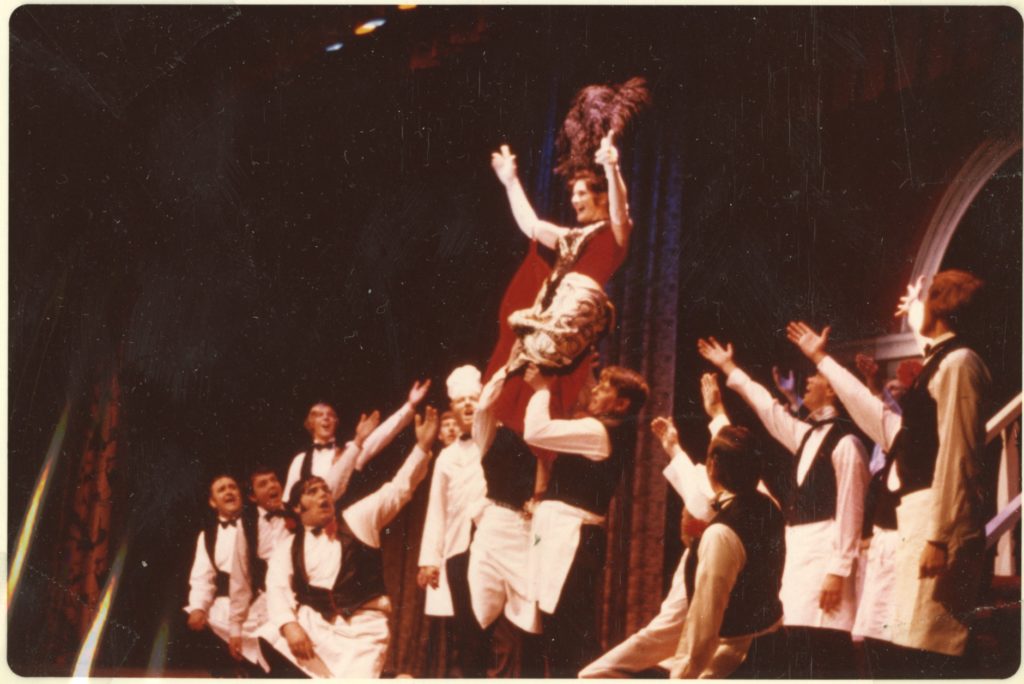

Stop by the library to see the brand new exhibit, Selections from the Westborough Players’ Club Records, in the display case outside of the Westborough Center, or learn more about this organization in the online exhibit.

* * *

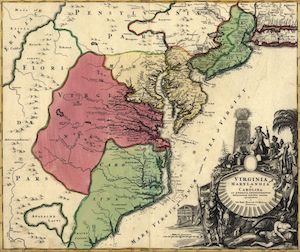

The Library of Congress has a great series of timelines that use primary source materials in its vast collection to illustrate the movement of history in the United States. The U.S. History Primary Source Timeline starts with colonial settlement in the 1600s and goes up to 1968 and the post-war era.

Generous text describes the period under consideration and is followed by a list of links that go to significant documents and historical materials that illustrate that time. It’s a great way to see, learn about, and understand the historical sweep of our nation.