Three BIG Questions

Unless we live in a large city, like Chicago or New York City, we tend to think about local history in small ways. The term “local” itself minimizes the apparent significance of the field through its implicit geographical comparison to larger histories, such as national or world histories. Yet, in a local history newsletter, no less, I am going to wax philosophical and encourage you to think big, really big. But don’t worry, I will circle back to local history eventually.

I have come to believe that we, as human beings, should be trying to answer three big questions throughout the course of our lives: 1) What does it mean to live a good life?; 2) How can we fully experience what it means to be human?; and 3) What is the meaning of life? I told you I was going big!

All three questions interrelate—although their subtle differences demand that each be tackled separately—and answers to one provides building blocks for answering the others. I am not going to pretend that I hold the key to answering them; besides, my answers will be different from yours, and the ones you develop will necessarily be deeply personal, unique, and subject to constant revision. Rather, I am more interested in arguing the value of asking each question and raising various ways to consider them.

In a society that increasingly demands quantifiable outcomes to justify our use of time and money on a given activity, the arts and humanities, with their more qualifiable outcomes, have become embattled fields over recent decades. Every year, arts and humanities organizations that rely on government funding must spend more and more of their valuable time justifying the value of their very existence, let alone maintaining the level of their budget lines (heaven forbid that they ask for an increase!). Humanities fields in universities are squeezed and eliminated, as students are encouraged to pursue more “practical” and high-paying majors, as though learning to live a quality life in the fullest sense of the term does not have any practical application. (By the way, studies have shown that while science and technology majors make more money right out of college, humanities majors out-earn them over time, because the latter are more likely to move into management positions later in life.)

And if my two chosen fields, English and history, think they have it bad, consider philosophy, which seems to remain the butt of everyone’s disciplinary joke. Yet, the fundamental questions about life that I pose above are taken directly from philosophy, and it turns out that these seemingly basic questions are extremely complicated to answer. Lucky for us, people way smarter than you and I (and most of humanity) have thought long and deeply about them and can provide guidance.

Why are these questions so important? Well, let’s look at the consequences of our recent neglect of the arts and humanities. We have technology companies founded by CEOs who may be brilliant with computers, but who generally failed to graduate from college and were never exposed to the arts and humanities in any deep and meaningful way. Is it any surprise that these CEOs now flounder while trying to make decisions about their companies and products, decisions that profoundly affect our society and the way we relate to one another? (I’m looking directly at you, Mark Zuckerberg—but he is not the only one.) We have influential people who manipulate history to justify their preconceived belief system rather than follow the facts to their logical, and sometimes contradictory, conclusions—and, perhaps worse, have people who actually believe them. And we have people who read and interpret art with the goal of dividing society, rather than see art as an ultimately safe space to explore new ideas and visions for our society, which we are then free to accept or reject.

I will address each of these three questions over the next three newsletters and in the process try to connect them to local history. I obviously will not have the space, nor the intellectual command, to consider the intricacies of each one in the way that philosophers have over millennia. The reading list below already suggests as much. But my ultimate goal is to help you consider your life in ways that can enhance and enrich your experience here on earth, which is the ultimate aim of the arts and humanities.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Next: What does it mean to live a good life?

Suggested Reading

- A Brief History of Thought: A Philosophical Guide to Living by Luc Ferry.

- How Philosophy Can Save Your Life: 10 Ideas That Matter Most by Marietta McCarty.

- The History of Philosophy by A. C. Grayling.

- History: Why It Matters by Lynn Hunt.

- Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts by Clive James.

- In Defense of a Liberal Education by Fareed Zakaria.

- College: What It Was, Is, and Should Be by Andrew Delbanco.

* * *

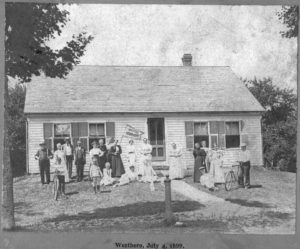

Eli Whitney has been on the minds of a lot of people in Westborough, given the recent controversy about whether the cotton gin should be removed from the Town’s logo because of its connection with slavery. Now is your chance to learn more about him through the Westborough Historical Society.

This Monday, February 22, 2021 at 7:00 p.m. on Zoom, Cary Mulrain, former WHS president, will present “Eli Whitney, Father of American Mass Production.” Westborough’s Eli Whitney (1765-1825) perfected the cotton gin to remove seeds from short-stem cotton and inadvertently increased the demand for slave labor on Southern plantations. He then went on to apply mass production to the manufacture of guns at the Whitney Arms Company in Hartford, CT.

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/86451366489?pwd=TkJ0SU9hV0VRc240bXo3UkFydnc2QT09

Meeting ID: 864 5136 6489

Passcode: 072932

Phone- Audio only:

+1 346 248 7799

Meeting ID: 864 5136 6489

Passcode: 072932

* * *

My mom was recently reading David McCullough’s The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West and came across a reference to Westborough in it. It turns out the wife of one of the book’s protagonists, Rufus Putnam, was Persis Rice (1737-1820), who was born and lived in Westborough before their marriage. You can learn more about her here: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Rice-2942.

Persis was a direct descendant of Thomas and Mary (King) Rice, the parents of four boys who were abducted by a group of Native Americans in 1704 and taken from Westborough to Canada to live with them. You can read what Rev. Ebenezer Parkman, our town’s first minister wrote about the episode (although Parkman was only a boy and did not live in Westborough at the time): https://archive.org/details/storyofriceboysc00park.

Thanks, Mom, for alerting us to our town’s reference in McCullough’s book!

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Local History Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox: https://www.westboroughcenter.org/subscribe-to-updates/.