Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project

By the time you read this newsletter, Juneteenth—a day that commemorates the end of slavery in the United States after the American Civil War—will be designated a national holiday (or will be soon). No matter the timing, Massachusetts already passed legislation to make Juneteenth an official state holiday, so the Westborough Public Library will be closed on Saturday, June 19.

As I think about the legacy of slavery and its history in our country, I can’t help but recount my experience of discovering the existence of slave narratives that were gathered together as part of the Federal Writers’ Project. New to the position as Humanities Librarian at Brandeis University, I was working in the stacks and familiarizing myself with the U.S. history collection when I came upon them. I was in awe that they existed and grateful that someone somewhere had the foresight to conduct these interview and capture this information before the memories disappeared with their owners.

The Federal Writers’ Project, part of the larger Works Progress Administration (WPA) that Franklin D. Roosevelt set up during the Great Depression, was designed to employ people who worked in the humanities. Other projects that fell under the WPA included ones for art, music, theater, and public works. Every time I encounter a building, public park, or artwork that was funded through the WPA, I am always blown away by the quality and ingenuity of the endeavor, which was why I was particularly excited when I found Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938.

The project was enormous. Over 2,300 first-hand accounts of slavery were collected along with more than 500 photographs. Today, the entire collection has been digitized and is available through the Library of Congress. The best way to approach this vast collection is through the “Articles and Essays” part of the website, which highlights just a handful of the people who were interviewed. A word of warning: a lot of the content, unsurprisingly, is difficult to take.

The collection is not without controversy. For years, the interviews were ignored by historians. Some of the reasons for this neglect stemmed from criticism that those still alive in the 1930’s were only children when slavery ended and so had unreliable memories. Others complained that despite the vast scope of the project, it included only 2% of the formerly enslaved population alive at the time and did not constitute an accurate “sample size.”

These reasons for neglect are pretty weak, but even though the collection is now firmly on the radar screen of historians, there is still reason to approach the collection with a certain amount of healthy skepticism. While some interviewers were African-American, the vast majority were white southerners, some of whom were descendants of slave holders and still others had ancestors who had enslaved the very people they were interviewing. Historical records are rarely straight-forward, which is why they require interpretation, interpretation that itself changes over time. You can read more about the Born in Slavery collection and the struggle to interpret it in an excellent article by Clint Smith in the March 2021 issue of The Atlantic.

In the end, the collection stands as testimony to the devastating effects of slavery on people and on our country. The economic, political, and social impact of slavery is so pervasive that it is impossible to untangle it from our national narrative in an attempt to create a “sanitized” version that we can all feel good about. Better to face up to its history, recognize the troubling contradictions that it created for our country both then and even now, and all work together to realize the ideals that we have so far failed to live up to but nonetheless form a common goal that will benefit us all.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Recommended Reading:

- Federal Writers’ Project, Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938 (Library of Congress).

- Clint Smith, “Stories of Slavery, from Those Who Survived It” (The Atlantic). If for some reason this link does not work, you can access it through the library’s Newsbank database (you may have to log in if you are trying to access it from home).

- Edward E. Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism.

- Wendy Warren, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America.

* * *

Coming Soon!

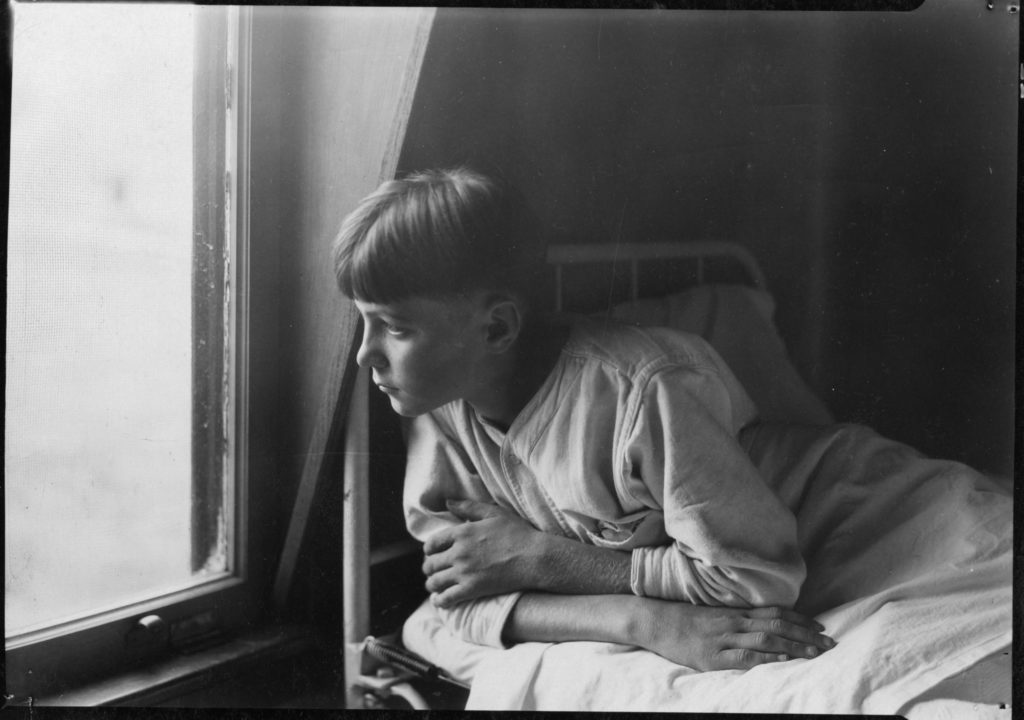

We are putting the finishing touches on installing a new exhibit here at the library, just in time for our post-pandemic opening. At some point next week, “Changing Pictures of Childhood: A Comparative History of Child Welfare in Westborough” will be displayed in the Westborough Center and on the main floor of the library.

The exhibit compares two different approaches practiced in Westborough to address the needs of children facing social challenges. Pauper apprenticeship—where poor children were bound by contract to work as a servant in another family’s home—was used in Westborough during the colonial period and the early years of the United States. Westborough was also the site of the first publicly financed reform school for boys, which later became known as the Lyman School for Boys. Photographs taken during the years 1905-1912 illustrate the lives of the boys during this time, roughly one hundred years after pauper apprenticeship. By comparing these two approaches towards child welfare, we gain a window into how conceptions of childhood changed historically over this period of time.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Local History Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox: https://www.westboroughcenter.org/subscribe-to-updates/.