Life at the Lyman School was highly regimented. Here is the daily schedule for the boys:

Life at the Lyman School was highly regimented. Here is the daily schedule for the boys:

Beginning of the day: 4:00 AM for dairy boys; 5:00 AM for everyone else

- March down to the basement for cold showers, and then dress in blue work pants, shirts, suspenders and boots.

- March off to a one-hour class in the central building and then return back to the cottage for a meal of bread, milk, molasses, soup or oatmeal.

- Clean up and chores around the cottage; if there was time left, the boys received unstructured time, where they could smoke, read, play cards or talk amongst themselves.

7:00 AM

- March off to work.

11:30 AM

- Return to the cottage for the main meal of the day.

- After lunch, another hour of work and a half-hour break for play.

- Change into collared shirts and ties and attend a three-hour school session.

6:00 PM

- Return to the cottage for a light supper of bread, milk and peach or prune sauce, followed by a recreational period.

8:00 PM

- Bed time.

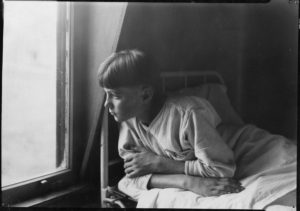

The administration of the Lyman School naturally put the school in the best possible light in its annual reports and promotional materials. But the school suffered from chronic overcrowding, which led to housing boys with serious criminal backgrounds along with others struggling more with psychological, emotional, and family problems.

James Gillespie Leaf, who wrote a doctoral dissertation for the Graduate School of Education at Harvard University on the Lyman School, describes the hostile environment that permeated the school:

When boys, unwanted by parents, neighbors, public schools, police or judges, were committed and crowded into residential groupings of 35 or more, they were hostile and often dangerous company. At different times outsiders to the institution characterized inmates as poor, defenseless children or as depraved offspring of the most brutal class of society. Regardless of the characterization, the constant reality was that very few men or women could stand to be with a group of them for long.

Because large and unpredictable feebleminded, emotionally disturbed and psychotic boys were prevalent in the school population throughout its history, staff always had to be concerned for their own physical safety as well as for that of smaller or less aggressive inmates.

Leaf’s historical research into the school also uncovered treatment where students pulled weeds, broke rocks, or shoveled coal as part of their “training,” and boys working in the fields were regularly attached to a ball and chain.

Use of tobacco was common among the boys, and after depriving food to boys was abandoned as a form of discipline after 1910, doling out tobacco became one of the primary ways to provide incentives and maintain discipline. Smoking was a common activity during relaxation time, and staff would purchase cigarettes to hand them out as rewards. Some boys saw taking up smoking as an advantage, because then masters were more likely to take away cigarettes as punishment rather than use corporal punishment or demerits for more milder offenses.

The Suicide of John Newman, 1910

A major scandal hit the school in 1910 when a fifteen-year-old student, John Newman, committed suicide while under the school’s watch. The Massachusetts House formed a committee to investigate the suicide and to look into conditions at the school. Newman’s parents, who lived in Cambridge, MA, committed the boy for being a “stubborn” child. The father testified to the House committee, “The boy would stay out late nights—stay out all night. He was getting stubborn, and wouldn’t mind me. I tried every way to control him, and when it was no use I had to put him away. I did it for his good. Once before I had him committed to a truant school because he would not go to school. He was unmanageable in that way.” Newman also engaged in theft.

Newman entered the Lyman School on May 28, 1910, and he was described as a “fair” student, who enjoyed physical activity, and got along with the other boys. He became interested in joining the band and in working in the printing office, and he was never reprimanded or punished.

After supper on June 6, 1910, the boys went outside to play, but when they lined up to return, Newman was not among them. After a thorough search, he was discovered at 11:30 p.m. in a Worcester Street Railway Company station on Lyman Street in Westborough. Newman had hidden in the cellar of the cottage where he stayed until the evening, and after the watchman had passed by with his lantern, he ran along roads and through fields and woods until he arrived at the railway station. He claimed that another boy had suggested the escape to him.

Once Newman was returned to the school, he was confined to a room in the Lyman Hall detention lodge. On June 7 the next day, he was served breakfast (six pieces of toast and a glass of water) and then left unattended from the morning until around 6:45 p.m., when supper was brought to him and his body was discovered suspended in a sheet fastened to the top crossbar of a grating.

The House investigation revealed that modes of minor punishment at the school consisted of walking or standing in line, sitting alone, deprivation of play, imposition of fines taken from the money the boys earned over time from the work they perform, and deprivation of certain kinds of food. The most serious forms of punishment entailed corporal punishment or putting the boy in a detention room. The House committee reported,

The implement used in administering corporal punishment is a soft, flexible rubber tube, 13 inches in length, attached to a wooden handle of the same length. The outside diameter of the tube is 5/8 inch, so that it is somewhat smaller than the garden hose in general use, and a little larger than gas tubing. The entire weight of the implement is 3.5 ounces. There are two of these implements at the institution . . . The number of blows given, according to the records, ranges from 8 to 45.

A record was supposed to be kept for whenever corporal punishment was administered, including the name of the boy and the number of blows. However, the committee discovered that such record-keeping was incomplete and inconsistent.

Even though the committee investigation uncovered some horrific practices and conditions at the school, the committee noted:

It should be remembered that the average boy sent to the school is one whom the home cannot manage, the church influence nor the public schools control. He is a boy who has shown a lack of appreciation for social conventions and restraints, and, unless he can be taught the necessity for obedience to proper authority, his reformation is well-nigh impossible.

The House committee went on to conclude:

On the whole, the boys were a contented, happy and healthy lot. The committee found no evidence, judging from the boys’ conduct, that they were browbeaten or in fear of their masters, and the school appears to be doing considerable good work in the way of training the boys for some useful occupation. . . . [I]t appears from statistics on the subject that over 60 per cent. of boys who leave the Lyman School apparently do well after their release. Taking into consideration all the problematical features of reformation, much credit should be attached to the work of the institution.

In the end, despite the scandal and the investigation of the Newman suicide, few changes were made to the system, and the House committee ended up endorsing the continued use of corporal punishment. But at the end of the report, one committee member submitted a forceful dissenting opinion that seriously questioned the value of corporal punishment and its use on the boys.

Go to the next page in the exhibit: Movie, 1946.

* * *

Exhibit Navigation for “Changing Pictures of Childhood: A Comparative History of Child Welfare in Westborough”: