What’s In a Name? Part II

In my last newsletter, I parsed out the name of the Westborough Center for History and Culture and explained why we selected it, so perhaps a review of how well the title reflects what happens behind its glass windows is in order.

As a Center, the program is designed to support the interests of people who wish to engage in activities relating to Westborough’s history and culture. How has this aim manifested itself so far? We started a Photographer-in-Residence program both to support the work of talented photographers in town and to add the documentation of life in Westborough that they create to the archives. We sponsored Architectural Walking Tours given by R. Chris Noonan and Luanne Crosby and worked with them to produce supporting documentation that shows Westborough’s architectural history. We also worked with two girl scouts, Emily Bartee and Kayla Niece, on a Silver Award project to create a self-guided architecture tour of Westborough’s downtown.

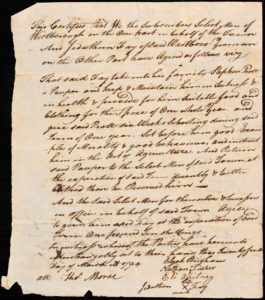

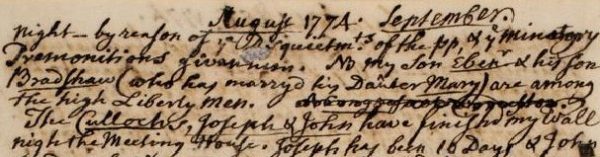

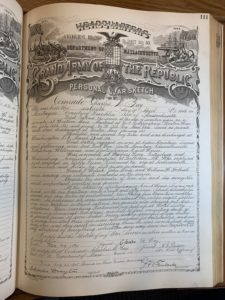

We have also partnered with people in town to publish and make available important records, documents, and histories relating to Westborough. We worked with the Town Clerk’s office to digitize all of our town records up until 1930 through the Digital Commonwealth, which includes the town’s handwritten copy of the Declaration of Independence. We also helped Kristina Nilson Allen digitize her seminal history of Westborough, On the Beaten Path: Westborough, Massachusetts, so that anyone with access to the Internet can now read it for free. And we have created a website, the Ebenezer Parkman Project, by working with two other scholars, Ross W. Beales and James F. Cooper, to make the entire diary of Ebenezer Parkman, Westborough’s first minister, available in one place and searchable for the first time. Overall, the website provides unprecedented access to a large number of historical records that make Westborough the best place to study colonial life in a rural New England town.

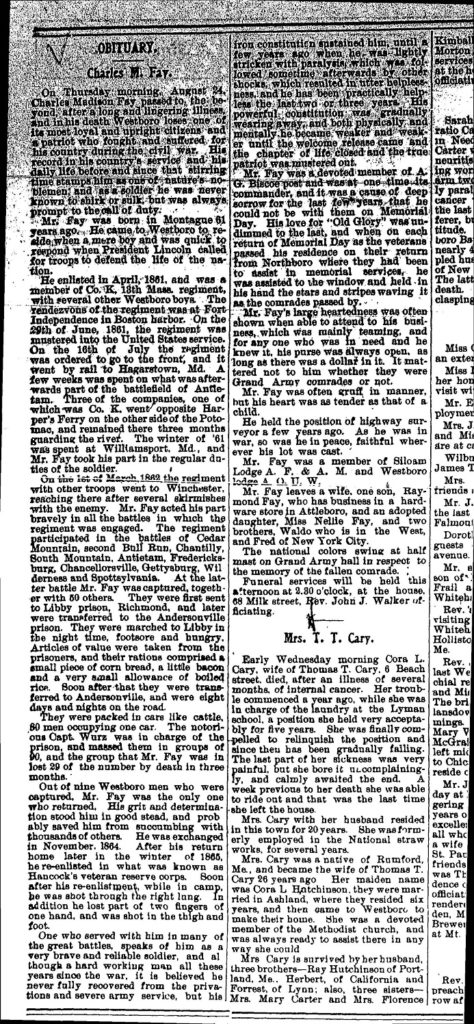

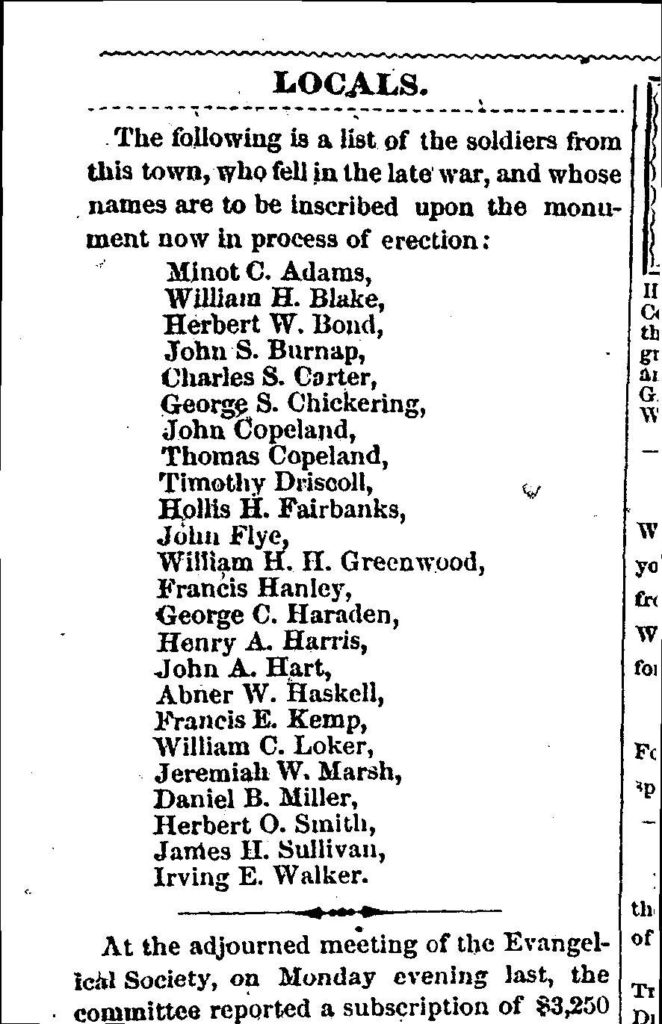

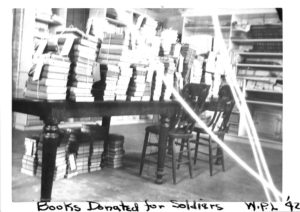

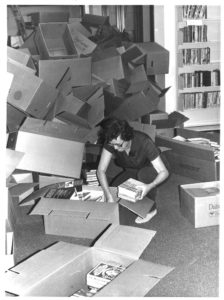

History, of course, plays a central role in the Westborough Center’s activity, so we have made the records that document the town’s history more accessible to everyone. Historical records that were hidden away, unorganized, and, as a consequence, generally inaccessible have now been boxed up, cataloged, and made discoverable through the Westborough Archive Catalog. People seeking information about a topic relating to Westborough can start here and identify collections that can help with their research. Some of the more important collections have been digitized and are available online at the Digital Commonwealth or in the Westborough Digital Repository. Westborough’s historical newspapers have also been digitized, so that sitting in front of a microfilm machine to read them is now in the past. And all of these resources and more are available through the Westborough Archive website.

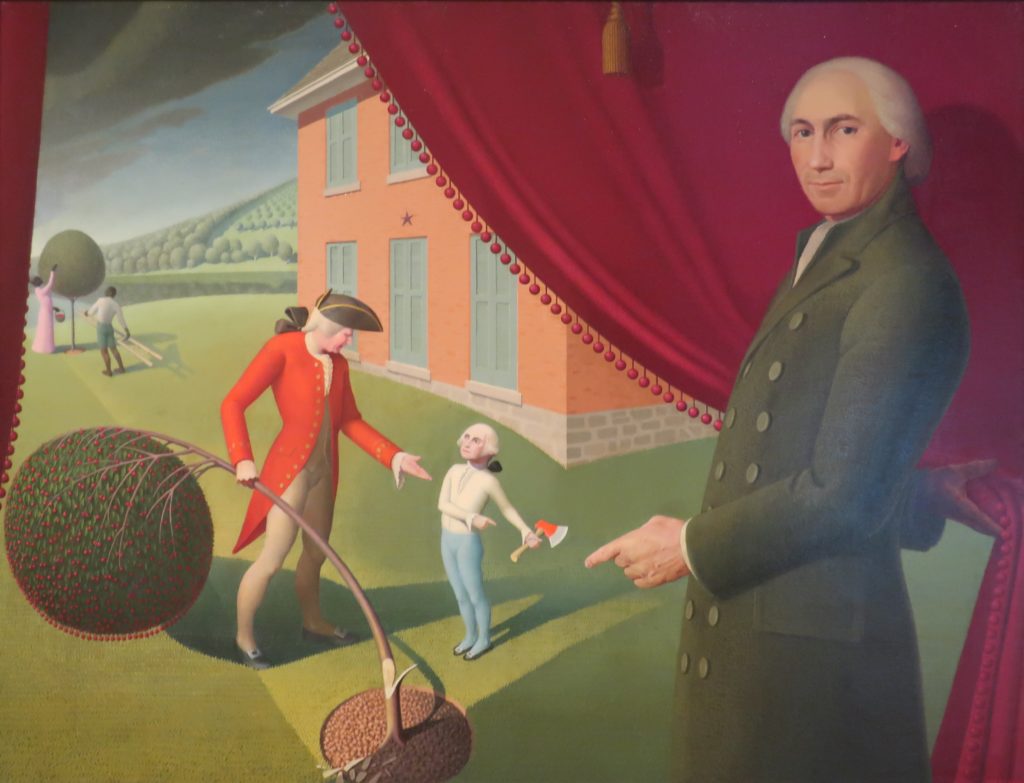

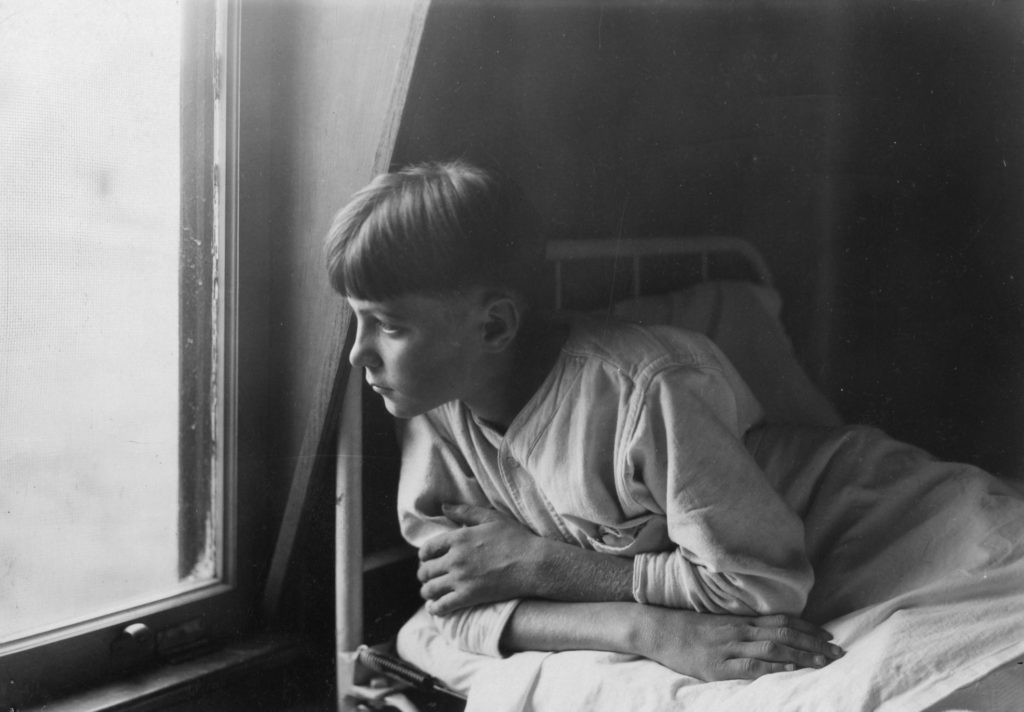

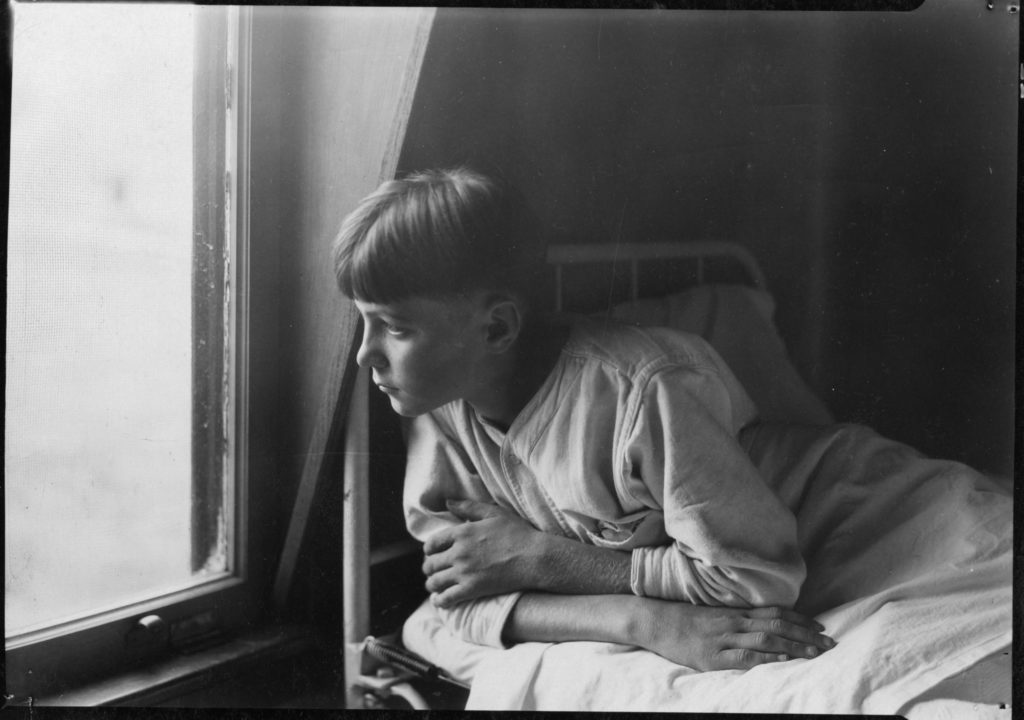

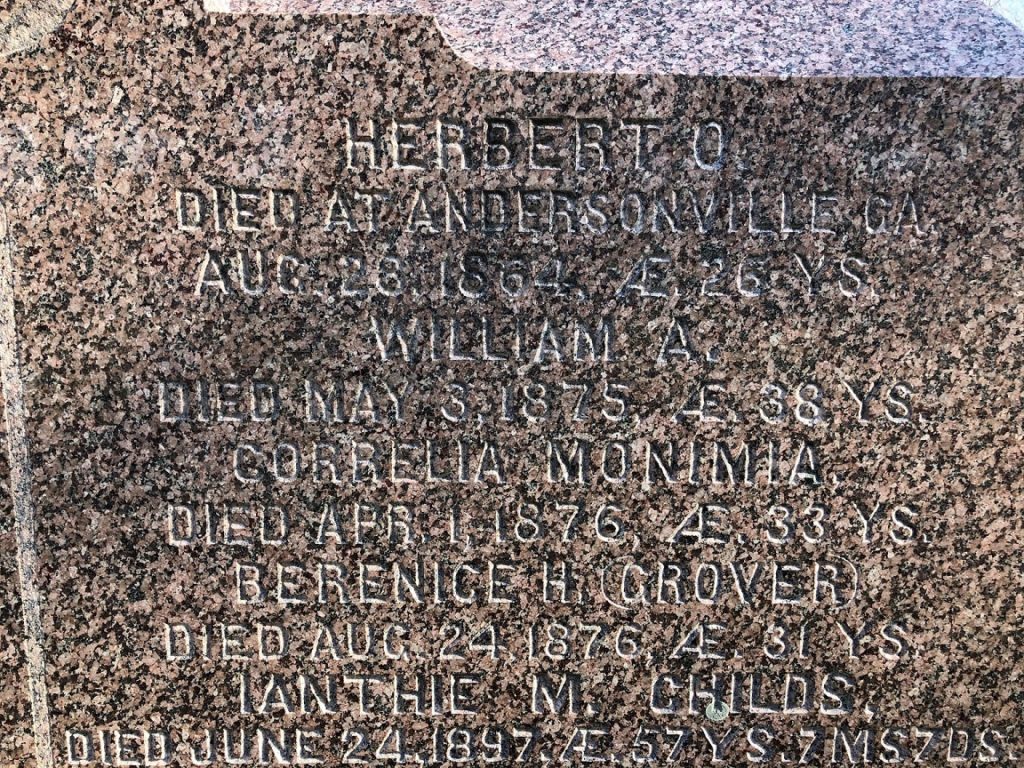

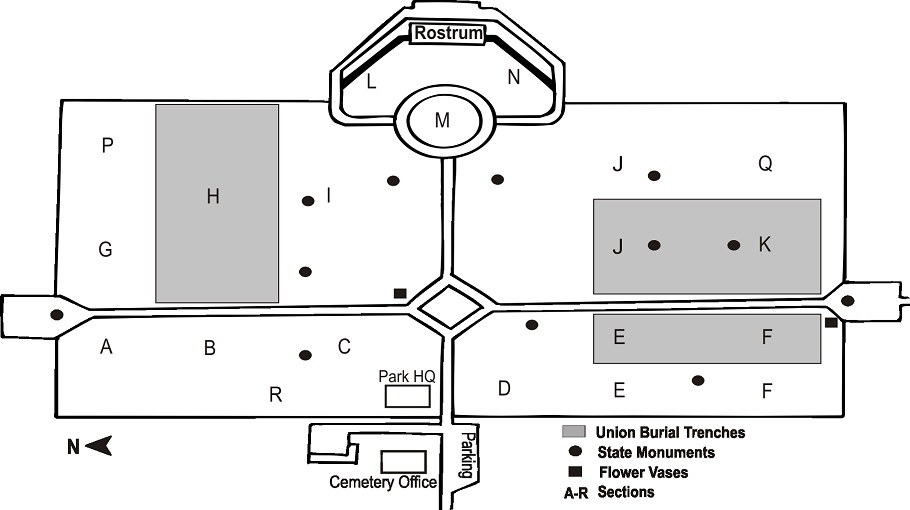

And finally, what about Culture? We regularly create exhibits and online publications that try to place Westborough’s local history into a broader cultural context. Our current exhibit, Changing Pictures of Childhood, connects local practices relating to child welfare to changing notions of childhood itself through history. Years ago, we published a series of blog articles under the title, “How Does History Connect Westborough and India?,” and we worked with Westborough TV and the Westborough Cricket Club to film an in-person program on An Introduction to the Game of Cricket. We also explored Westborough’s folk tales through another program and then published them online as another blog series.

Unfortunately, many of these activities have been curtailed due to the pandemic, but our sincere hope is that we can get many of them up and running again in the near future. So if you have any interest in exploring Westborough’s history and culture, or perhaps even working with us to create an exhibit, a program, or an article to share your local knowledge with the community, we are here to help.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Recommended Reading:

- There is lots to explore through the Westborough Center for History and Culture’s website. Take a look!

* * *

One of the strengths of Westborough is its green spaces. Are you curious about the wild plants and animals you might see locally in September? Check out the Westborough Community Land Trust’s online monthly Nature Notes index for September, written by Annie Reid. All of the listed articles for the month continue to be relevant today!

* * *

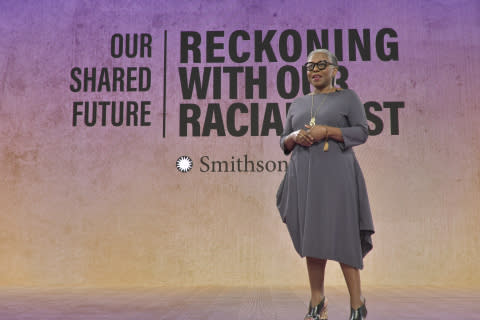

With its focus on history, culture, and knowledge, the Smithsonian Institution serves as a model of inspiration for the Westborough Center. In many ways, we try to replicate the spirit of inquiry that it represents and to use its leadership to explore themes that affect us at a more local level here in Westborough.

This summer, the Smithsonian Institution has launched an institution-wide initiative, Our Shared Future: Reckoning with Our Racial Past, to explore the history and legacy of race and racism in the United States and across the globe. The initiative will include a series of integrated events across the U.S., including conferences, town halls, and pop-up events. The hope is to spark conversations in a safe space among people who may normally never interact with one another about a topic that can admittedly become uncomfortable. The first forum on Race, Health, and Wealth was held just over a week ago, and it can now be viewed online.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Local History Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox: https://www.westboroughcenter.org/subscribe-to-updates/.