The Documentation of Westborough History

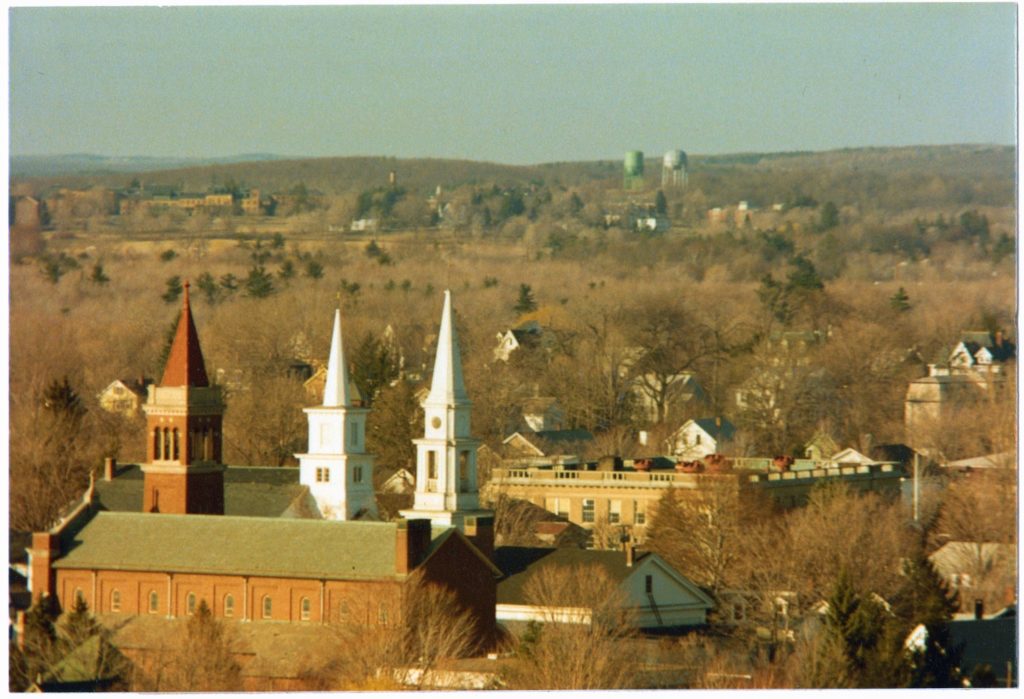

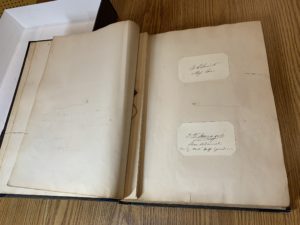

I often assert that Westborough is the best town for studying rural life in eighteenth-century New England. Why? Because Rev. Ebenezer Parkman, who served as Westborough’s first minister from 1724 until his death in 1782, kept a detailed diary of his life and interactions with people in town throughout that time. And when we combine the information in his diary with his thorough church records and Westborough’s near-complete town records, no other rural New England town offers the depth of documentation that we do during this time period.

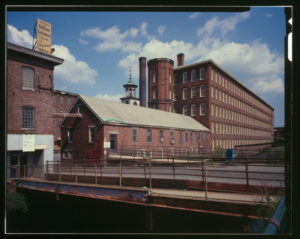

But documentation of Westborough’s other historical periods isn’t too shabby either. As a bustling industrial town in the nineteenth century, Westborough attracted numerous photographers to its downtown, who naturally turned their cameras to the streets and buildings when they weren’t aimed at families seeking family portraits. The library has a collection of newspapers that go back to 1849, and even though we have occasional gaps, the long run of the Westborough Chronotype from 1871 to 1965 ensures that these gaps are relatively minimal. And we have a complete run of the Bay State Abrasive Products company newsletter, among other resources in our library, not to mention the great historical collections in the Westborough Historical Society and the Westborough Historical Commission.

But what if this deep documentation of our town’s history didn’t exist? How would we figure out how the people of Westborough lived back in history and how their lives changed over time?

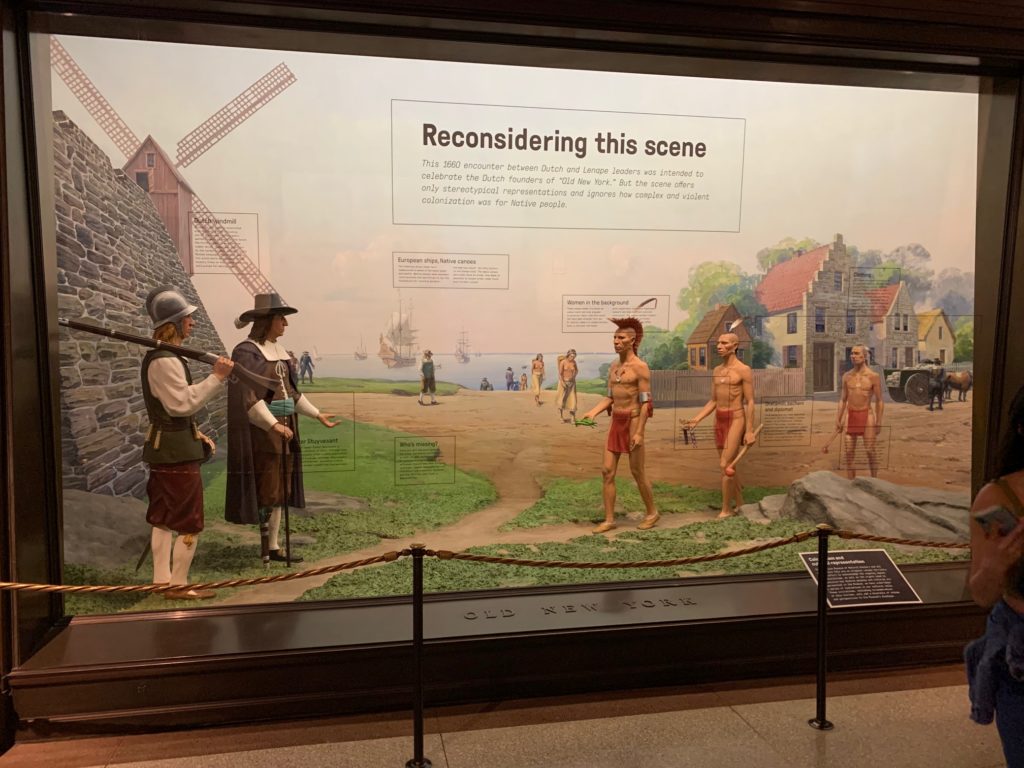

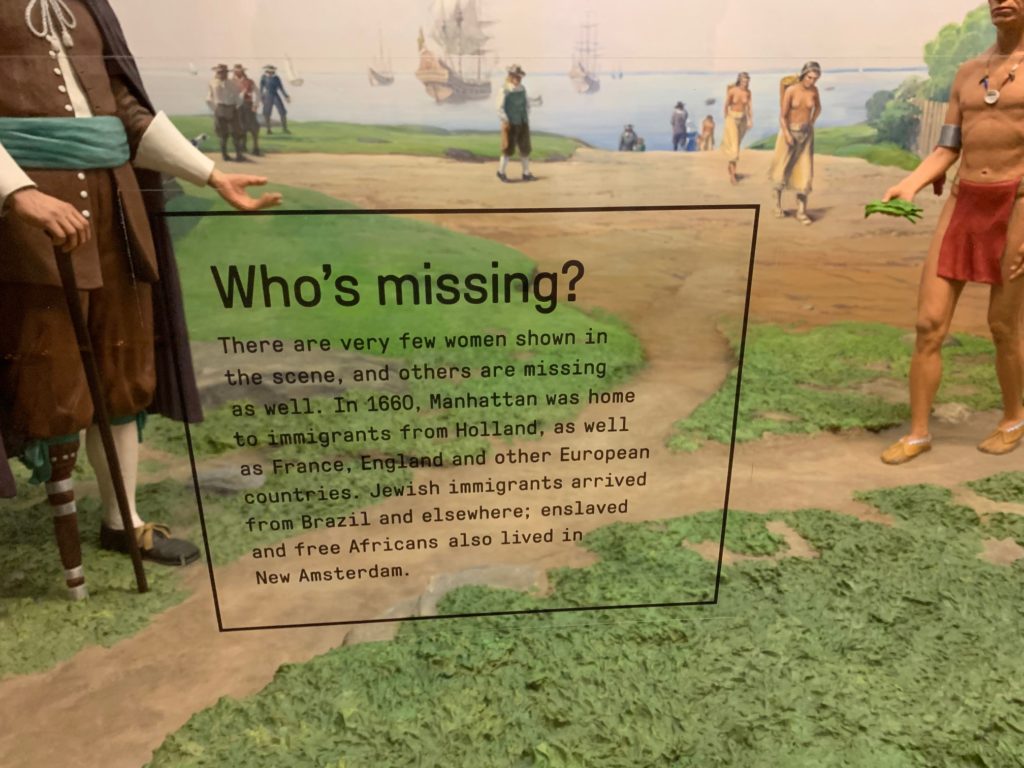

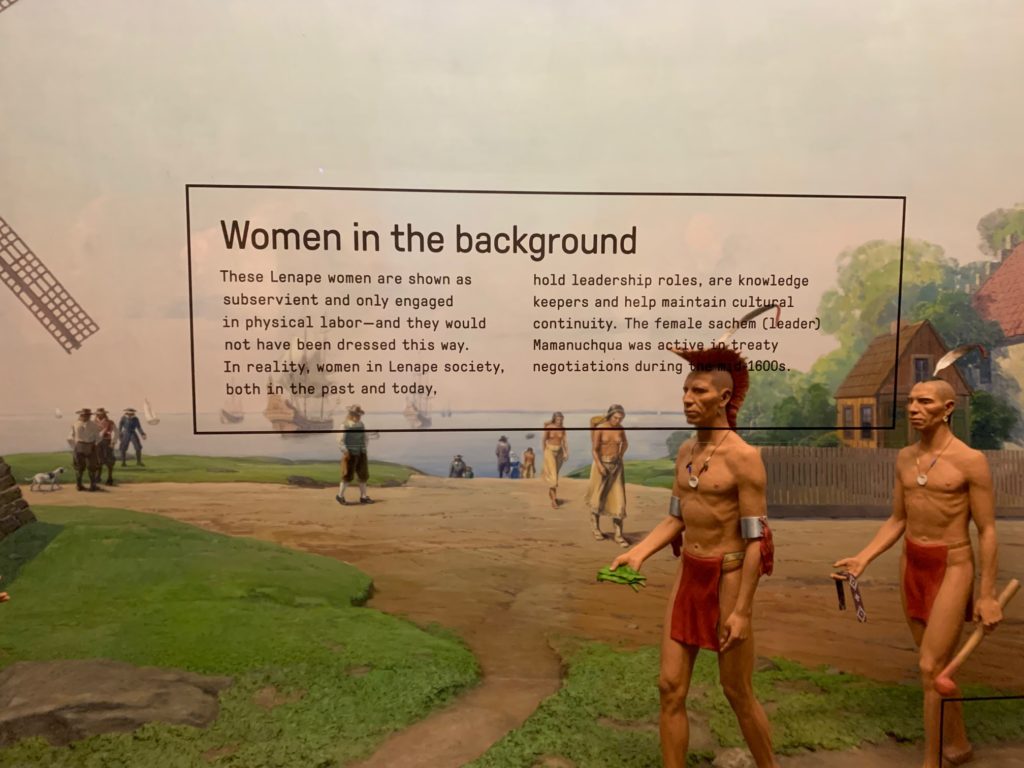

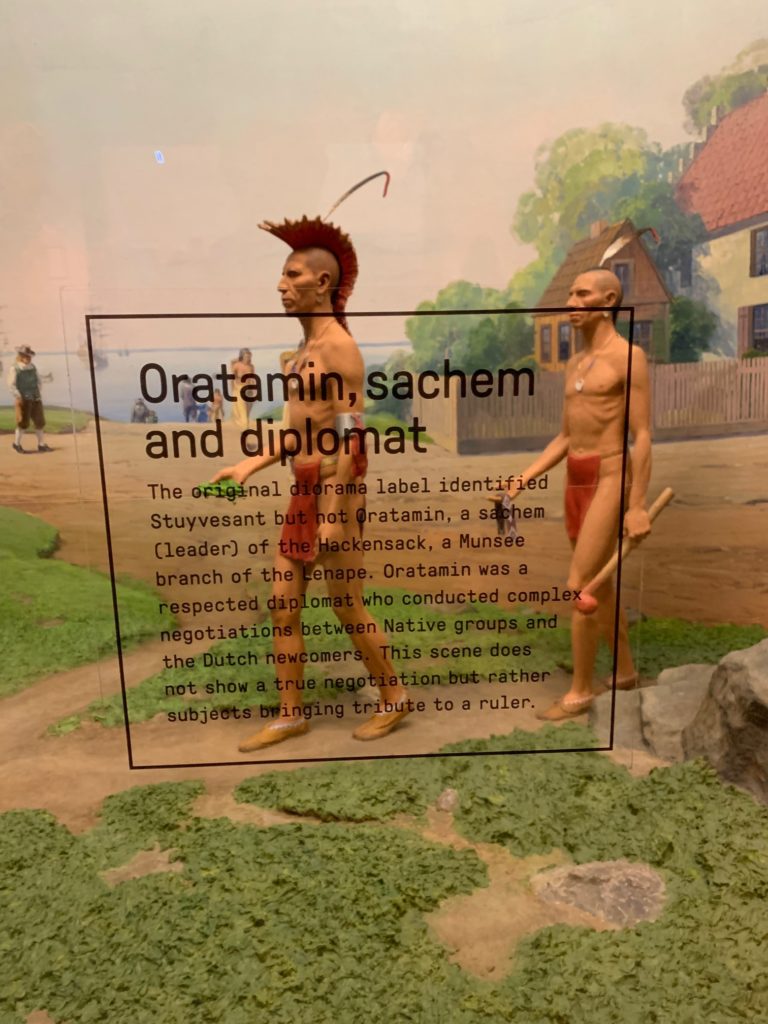

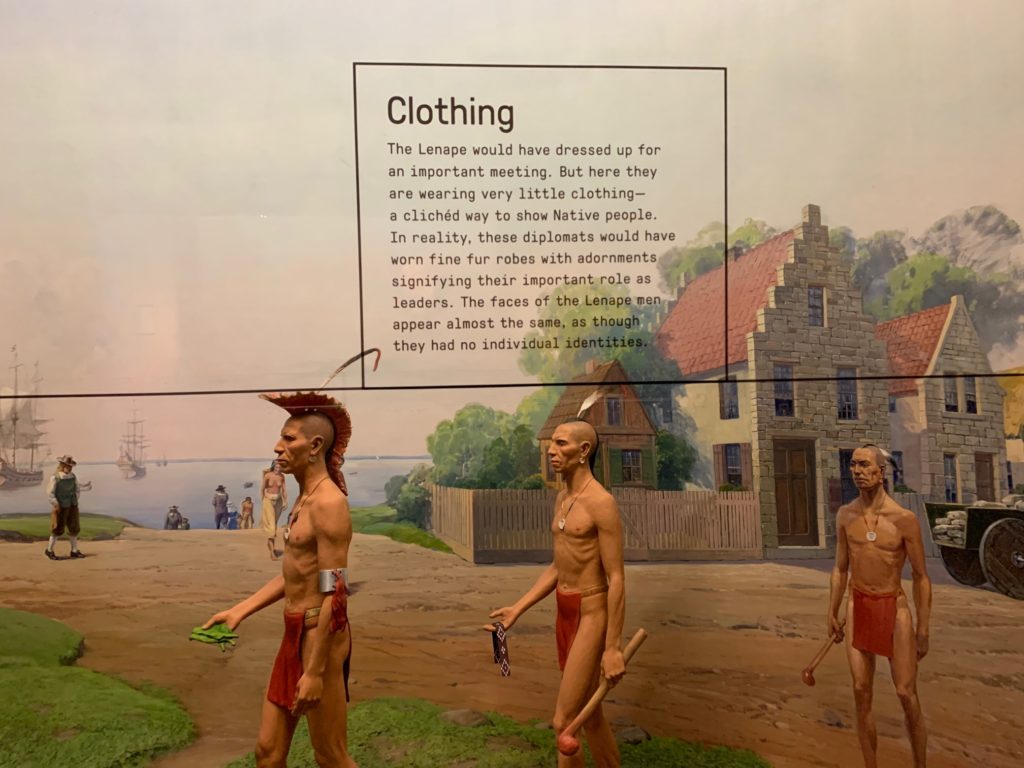

Lately, I have been reading histories of indigenous people in the Americas before and during the first moments of contact with Europeans, because if we truly want to understand why you and I live in Westborough today, we need to learn how and why people came to inhabit this area in the first place. But the problem in researching this information is that the native people who first lived here during that time did not have a form of writing, so we have no documentation about what they ate for dinner, what they thought about their neighbors, or what major events affected their lives.

Until relatively recently, the only way we could learn about the lives of the people who lived here before European contact was from accounts written by the first Europeans who saw them. As Charles C. Mann, the author of the book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus, puts it, “Paradoxically, [my] book about life before Columbus spends more than a little time discussing life after Columbus” (xi), because that is when we have the very first written documentation of the lives of indigenous people who actually lived before Columbus landed. Of course, the challenge in using these records for historical purposes is that the accounts are from a decidedly European perspective, so we have to read between the lines and look closely at how these chroniclers describe both the life and the reaction of native peoples to their sudden presence.

With this insight in mind, I decided to look at how some of Westborough’s early histories, which mainly date from the 1890’s, portray Native American life. What can we learn from these resources about the lives of the people who first inhabited the land where we live now, keeping in mind, of course, their limitations and European perspective? In months to come, I will have more to say about what I discovered, but if you want to take a look and see what you can conclude from these histories yourself, the bibliography at the end of this article contains links to the ones I have consulted so far.

Today, as Mann goes on to point out, new disciplines and new technologies can add to and give us a better understanding of the historical period before European contact beyond these early histories. They include, “Demography, climatology, epidemiology, economics, botany, and palynology (pollen analysis); molecular and evolutionary biology; carbon-14 dating, ice-core sampling, satellite photography, and soil assays; genetic microsatellite analysis and virtual 3-D fly-throughs” (17). All of these methods are radically changing our understanding of pre-Columbian America.

While looking for early Westborough histories on the reference shelves in the Westborough Center, I also came across a book by Curtiss R. Hoffman called People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts. The book is an archaeological survey of “the lifeways of the prehistoric peoples of the town of Westborough, Massachusetts over the past 9000 years” (back cover). Hoffmann published his book in 1990, and in the Introduction he claims, “Writing the prehistory of a town is not nearly as simple a task [as writing a history based on historical records and previous histories], and this is undoubtedly one reason why it has never before been attempted in Massachusetts, or, to my knowledge, anywhere else in New England.”

I have yet to read Hoffman’s book, but a quick search for similar books seems to verify that his claim that his is the only attempt to write about the prehistory of a New England town still holds true. Once again, Westborough may very well be the best town to study life in a rural New England town, only this time before European contact and before our town was even a town.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Suggested Reading:

- The Ebenezer Parkman Project

- 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann.

- The History of Westborough, Massachusetts by Heman Packard DeForest and Edward Craig Bates. Online edition.

- The Hundredth Town, Glimpses of Life in Westborough, 1717-1817 by Harriette Merrifield Forbes. Online edition.

- People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts by Curtiss R. Hoffman.

* * *

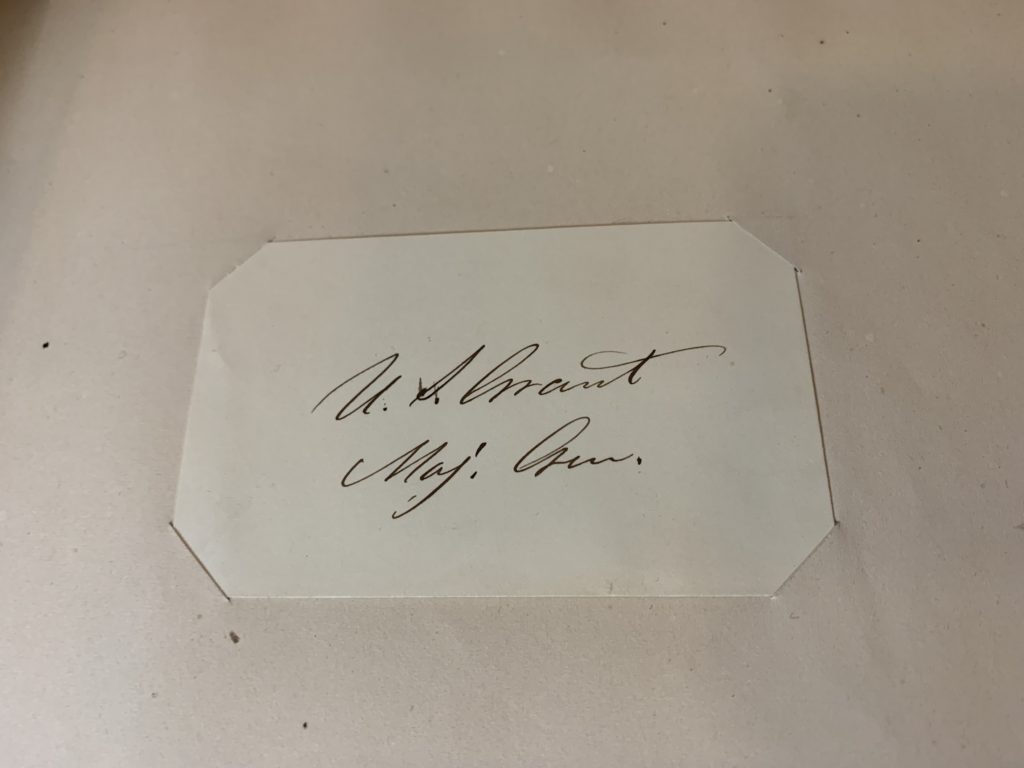

We Got the Grant for Our Library Renovation!

On July 7, 2022 the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners awarded $9.4 million to the Westborough Public Library to put towards its library renovation. Final approval for the project will go to Town Meeting this fall.

This building project is extremely important to the Westborough Center for History and Culture, because it will help us to continue to collect and save Westborough’s historical records and documents for years to come. (Did you read the article above about documentation and the difficulty of piecing together history without it?) Right now, we have basically run out of room to house our important historical records in the current library structure. The library renovation will allow us both to house current and future collections in updated, climate-controlled conditions and to communicate their significance through display, exhibits, and programming.

I urge you to learn more about this building project. Attend the Public Forum for the Library Building Project on Tuesday, July 19 at 7 p.m. at the library or visit the Building Project website.

* * *

How Local Is Local?

You can ponder this question as you view the latest images from NASA’s newly deployed James Webb Space Telescope. The new telescope will enable astronomers to look further back in time and space than they ever have before, practically back to the universe’s first origins 13.8 billion years ago. One image already gives us a view of light emanating from distant galaxies that is 13.1 billion years old (and consequently 13.1 billion light years away). Suddenly, even World History seems very local!

* * *

Nature Notes: July

The Boston Red Sox are a dreadful 0-9 in series against American League East teams this year. But let’s not hold their poor performance against the Baltimore orioles that make hanging nests around this time in our area. Learn more about how to spot these special nests and other natural wonders in Annie Reid’s Nature Notes for July.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.