Becoming America

There is nothing more American than to talk about who we are and what we want to be. People from other, older parts of the world do not experience the constant identity crisis that we do. After all, they live in cultures that have had the chance to coalesce over a much longer period of time. But Americans are always in search of the new, and attempts to pin down and define who we are always seems to disintegrate in the face of historical and cultural contradictions, which then starts the cycle of trying to define who we are all over again.

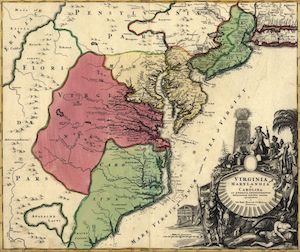

The American concern over who we are and what we want to be is partly the result of the unique history of where we live. When Europeans started to move to the Americas and inhabit the “New World,” they saw a land that offered new and endless opportunities (although, as we well know, this liberatory move also involved displacing and subjugating the people who lived here before them and set up one of America’s long-standing and defining contradictions). As a consequence, those of us who live in the Americas—and when I say “the Americas” I include both North and South due to our shared historical development and common cultural outlook—we focus more of our attention and efforts on creating the future than on preserving the past, and we work hard to realize our vision for what we believe will be a better society for us and for future generations. America and Americans, in short, are always in the process of Becoming.

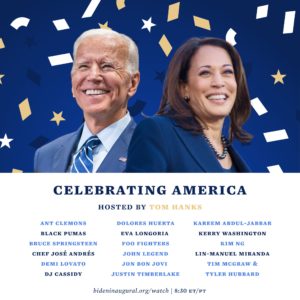

Amanda Gorman captured the essence of these reflections in a much more articulate way in her electrifying poem, “The Hill We Climb,” which she read at the Presidential Inauguration Ceremonies on January 20, 2021. Gorman and her poem justifiably became the talk of the Inauguration, and there is no shortage of available commentary and analysis of her poem on the web and in the media. But as I listen to and read her words, the spirit of Walt Whitman flashes over me, especially his poem, “I Hear America Singing” (1860) from Leaves of Grass:

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,

Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong,

The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work,

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deckhand singing on the steamboat deck,

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands,

The wood-cutter’s song, the ploughboy’s on his way in the morning, or at noon intermission or at sundown,

The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of the girl sewing or washing,

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else,

The day what belongs to the day—at night the party of young fellows, robust, friendly,

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.

Whitman’s poem lacks the verbal pyrotechnics that Gorman commands in hers, but both show how our shared sense of possibility can lead to unity. Whitman’s poem singles out the “songs” that each worker creates during the course of plying his or her trade. While all of them are hard at work trying to improve the lives of them, their families, and, consequently, of America, each one of them is unique and special, with “Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else.” At night, the young ones abandon their daily differences to congregate and join together in “strong melodious songs.” But for the poet, the “varied carols I hear” of all of their work during the day come together to create the true song of America.

The work of being American is never finished, as much as we may want to reach that end goal and revel in our finished product. Our economic system values the latter, but our democratic system demands the former. This contradiction is also a part of what makes us who we are. We justifiably get frustrated when we seemingly fail to realize our individual political goals and desires over and over again. That’s the time, however, when we need to step back and recognize that even though we are all singing different songs, that the cacophony that we are creating is America and is the sound of our Becoming.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Suggested Resources

- Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville.

- The Walt Whitman Archive (website).

- Amanda Gorman (website).

- “’For there is always light’: Amanda Gorman’s Inaugural Poem ‘The Hill We Climb’ Delivers Message of Unity” (Library of Congress website) by Peter Armenti.

* * *

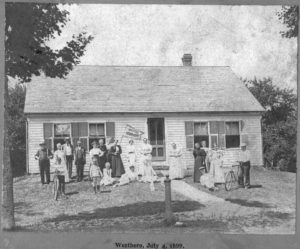

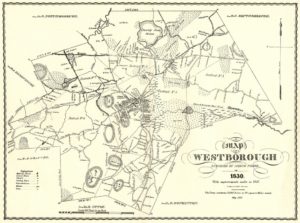

Along with poetry, photographs have the power to help us visualize the Becoming of America. The Westborough Digital Repository has two collections that, when put side-by-side, illustrate the Becoming of America at our local level here in Westborough.

The Historical Photographs of Westborough collection covers Westborough’s early history and the Photographer-in-Residence collection of photographs by Brandin Tumeinski give a more recent look at Westborough becoming what it is today. Take some time to browse through both collections and think about where we have come, what we are now, and what we can be in the future.

* * *

In a past newsletter, I discussed the importance of building historical timelines in our mind while learning about history (although we also want to be careful not to fall into the trap of thinking that history is merely a set of dates and events!). Here are two more websites that can help us build our historical timelines, one more worldly and one more local.

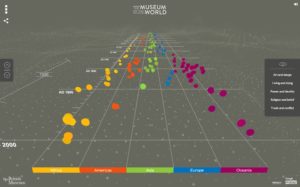

- The Museum of the World from the British Museum – This collaboration between the British Museum and the Google Arts and Culture Lab allows you to explore items from the museum’s collection and connect cultures and ideas through an interactive timeline. Click the “Launch Experiment” button to get started and enter a 3-D world of culture, time, and place (unfortunately, the website only works on desktop computers).

- MassMoments a project of MassHumanities – This interactive timeline provides both a daily “This day in Massachusetts history” entry and a way to explore Massachusetts history chronologically through the years. You can also sign up to have Daily eMoments delivered every day to your e-mail address.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Local History Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox: https://www.westboroughcenter.org/subscribe-to-updates/.

Renewal

Renewal