Memory, Identity, and History

In the opening to Marcel Proust’s epic novel, À la recherche du temps perdu (variously translated from the French as In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past), the narrator reflects on those times when we lie half-asleep in bed and inhabit a world that seamlessly flows in and between dreams, memory, and our waking identity. During these moments, we lose track of who we are. What is dream and what is reality? Are the memories that pass through our head real, what is our present self, and is there a difference between the two?

We are who we are as individuals because we have memories that are unique to ourselves. Memory anchors us to our past. Without it, how do we know who we are? We only overcome those moments of indecision about who we are, those moments that Proust describes, after we slowly piece back together in our heads the primary narrative of our past that we use to formulate both our present identity and our sense of who we are. Once morning arrives, we get out of bed, start our day, and continue to add to the narrative of our life.

In similar ways, memory is central to our notions and practice of history. History is the cumulation of narratives that we tell ourselves in order to help us better understand who we are as a people. This cultural memory helps us to explain why we as a people do some of the things that we do, believe some of the things we believe, and got to be who we are.

But as central as memory is to shaping who we are as individuals and who we are as a society, we also know that memory can be faulty. As individuals, we sometimes remember events as we want to remember them, not as they truly happened. We even forget large portions of our lives entirely on a regular basis. We forget because many moments of our life are so seemingly mundane that they would take up too much brain space to make remembering them worthwhile. At other times we forget because some events are too traumatic or simply unpleasant to revisit, and in these cases, such forgetting can happen either willfully or unconsciously.

We often distort memories or suppress them because their reality does not neatly fit into the primary narrative of our past. Better to sacrifice the individual memory than to upend entirely the narrative that we have been piecing together in our head throughout our life. Of course, such distortions draw into question the validity of our own personal narrative, and when that narrative is corrupted by so much distortion that it impedes us from functioning in reality, many of us go into therapy in an attempt to rewrite it.

Faulty memory also happens in history. Sometimes we discover evidence that had been hidden away or went unnoticed for whatever reason. But like our individual memory, we are always “forgetting” elements of lived experience when we write history. We highlight certain facts and suppress others in order to create a more coherent narrative. And like our individual memory, sometimes these forms of “forgetting” are willful while others are unconsciously carried out.

When the distortion we use to uphold the history that we tell ourselves becomes too great in the face of contradictory evidence or competing narratives that can better accommodate known evidence, such historical narratives drift more and more into myth. Myths can still tell us a lot about ourselves both as individuals and as a society, but such stories have also lost their grounding in truth and consequently their grounding in history.

After I drafted the above reflections, I saw an article in the New York Times on September 29 about a group of historians calling to make “More History.” The idea is to fill in more details in our histories, details that have either been forgotten or ignored, so that we can tell a fuller story about ourselves than we have in the past. History, like much else in our society lately, has become politicized and is used to divide us. Maybe now is the time to engage in some historical therapy, to recover some of the gaps in the national narrative that we tell ourselves, so that we can create a better, fuller, and less divided understanding of who we are and how we got here.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Suggested Reading:

- Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust, translated by Lydia Davis (the first of seven books that make up the novel, À la recherche du temps perdu) (https://bark.cwmars.org/eg/opac/record/693468?locg=135; also available free online in a different translation and as an audiobook)

- “Beyond the Statue Wars: Restoring Erased History,’” The New York Times, September 29, 2020. (Gale Onefile)

- The Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud (available free online)

- Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape by Lauret Edith Savoy (https://bark.cwmars.org/eg/opac/record/3643693?locg=135)

- Letters to Memory by Karen Tei Yamashita (https://bark.cwmars.org/eg/opac/record/4093338?locg=135)

And see below for some ways to add “More History” to our understanding of Westborough.

* * *

(American Antiquarian Society)

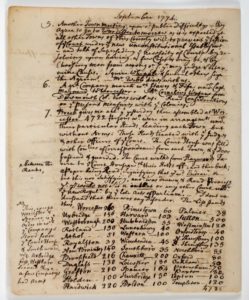

The Ebenezer Parkman Project – Every time I read sections of Rev. Ebenezer Parkman’s diary, I learn something new and profound about Westborough’s colonial history. Parkman scholar and professor Ross W. Beales, Jr. has compiled a list of all the instances when Africans and African-Americans appear in Parkman’s diary (PDF link). Surprisingly, his list is eleven pages long and its contents raise questions about our common notions about New England and its participation and role in the practices of slavery.

* * *

Another rich source for discovering hidden or forgotten aspects of Westborough history is our deep archive of historical newspapers, which go back to 1849. The archive is freely available online, so pull up an early issue or two and be prepared to be transported to another place and time.

* * *

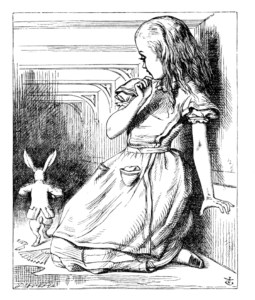

American Memory was an early Library of Congress digitization program, but the library has recently migrated all of these early collections into their centralized list of all digitized collections. The breadth and depth of content is breathtaking, and there is sure to be some topic that will catch your eye and lead you down into a rabbit hole of strange yet familiar history.

Another thoughtful essay. Worthy of reading more than once and sharing it with my friends and family. I so look forward to your postings.

Thank you so much, Jan, for your kind comments! It’s nice to know that I have a readership, and I look forward to the time when we can all have more in-person interactions about our town’s history.

I concur with Jan. Thank you for delving into Westborough’s history for us and for providing us with a wealth of resources as well. I have lived here long enough to remember the most recent past iteration of the “Westborough Chronotype”. I miss it!

Thanks, Anne! I hope you have as much fun as I do exploring the old Westborough Chronotypes.