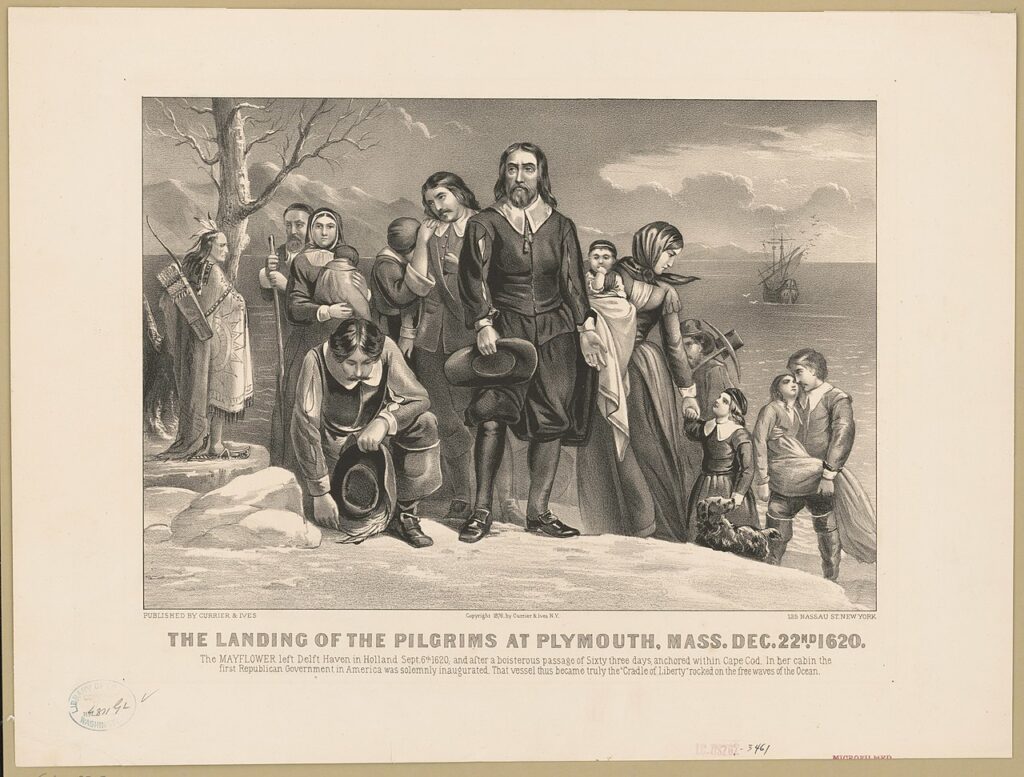

This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Land Use, Part II: Settler Colonialism and the Case of the Pig

[O]ur fathers had plenty of deer and skins, our plains were full of deer, as also our woods, and of turkeys, and our coves full of fish and fowl. But these English having gotten our land, they with scythes cut down the grass, and with axes fell the trees; their cows and horses eat the grass, and their hogs spoil our clam banks, and we shall all be starved.

—Miantonomo, a Narragansett sachem, 1642

Last month, we learned about the contrasting philosophies and epistemologies between Native Americans and Europeans towards land and property. This month, we are going to look at the real-world consequences of these differing thought systems on the New England ecology and environment as these two human ways of living in, and belonging to, an ecosystem came head-to-head.

Early descriptions of the natural abundance of the New World were fueled by the belief that returns on human labor would be greater here than in England. Written accounts of North America with their long lists of animals, fish, fowl, fruit, and edible plants that could be found here for the taking were aimed at wealthy merchants who were eager to put up money to extract these resources and turn them into commodities. But these written accounts presented a false picture of the reality here in New England, because they were mainly written in the spring and summer. The settlers who arrived here with the promise of “laborless wealth” soon realized that the New England climate was similar to their own back in England and that they would need to account for the natural rhythm of the seasons. Life in the New World, it turns out, was going to be a struggle until they could recreate the annual agricultural cycles that they were familiar with back in England.

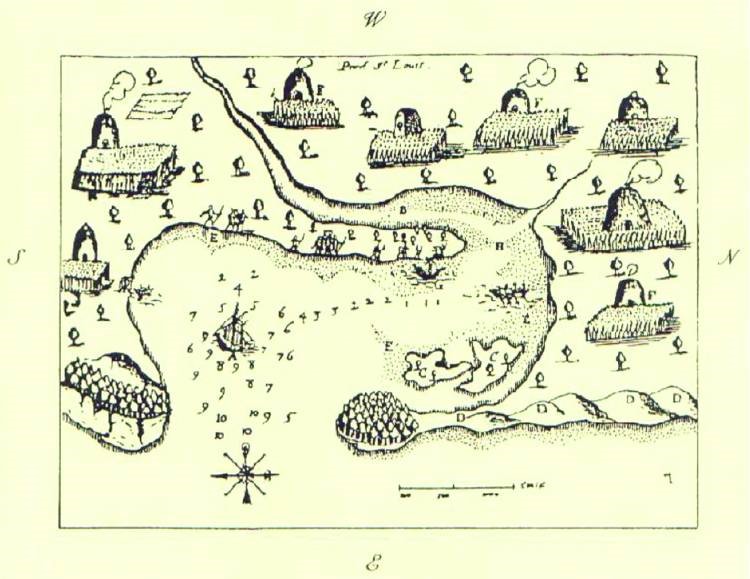

Europeans who settled in New England tended to occupy high ground, whereas Native Americans generally rejected this land as suitable for their villages due to its rocky composition and instead gravitated towards what might be considered more out-of-the-way locations, such as swamps. Swamps were vital to Indian life by providing year-round food resources, wood, water, and transportation routes. Indeed, accounts of late interactions between Westborough townspeople and Native Americans in the nineteenth century all take place around Cedar Swamp.

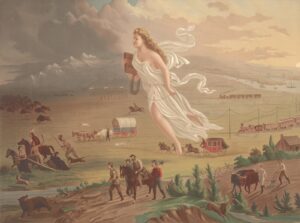

While Native Americans moved throughout the land in a patchwork of communities guided by the principle of finding maximum abundance through minimal work during each season, the English imposed order on the land with permanent settlements, even if doing so required much more work. Such fixity—with its cleared fields, pastures, buildings, and fences—directly clashed with Native American mobility. This difference created a struggle between two incompatible ways of living on the land and served as a central conflict between the two groups.

Agricultural production by Native Americans put its European equivalent to shame. Corn yields per acre were roughly the same for both Native and European people, but the former did so using far fewer corn seeds, which provided more space to grow beans and squash concurrently on the same plot of land. In order to produce the same yields as Native Americans, Europeans had to plant their corn more densely and use much more effort. The “Three Sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—also provided a more balanced diet than the European single crop provided on its own. Contrary to the myth about using fish to fertilize corn, Indians did not fertilize their fields. Such a practice was unnecessary and required too much work. Once a field’s fertility was used up, they simply moved on and planted their seeds in another space. But Europeans, because they “owned” their land, had to spend extra effort fertilizing their fields every year to keep them productive.

The very first European settlements were established on land that had already been cleared by Native Americans (who either had abandoned fields for others or had died off due to disease), by beavers (before they were hunted to near extinction), and by annual river floods. But eventually farmers needed to move into the New England forests and clear their trees in order to increase their land-holding. Such work was brutal, so enslaved Africans and indentured servants were brought to New England to clear forests and “improve” the land (enslaved local Indians, because the risk of them rebelling on their home turf was too great, were shipped off to the West Indies). The English used the downed trees to build ships, houses, and fences to keep livestock out of their fields. These fences severely limited Native American movement and disrupted migration routes of deer and other game that served as important food sources for them. By 1830, settlers had completely cleared 60 to 80 percent of New England’s forests, which radically altered the ecosystem. Over the now-clean expanses, Europeans sowed a single crop per field, allowed livestock to consume any stubble, and planted crops repeatedly until the soil was depleted. This soil was now more subject to erosion, and the monoculture planting encouraged specialized weeds and insect pests to take hold.

The English, however, had one major agricultural advantage over Native Americans: domesticated animals that could be used both for food and food production. While Native Americans relied solely on seasonal hunting and fishing for their animal protein, Europeans mainly controlled the source of their animal protein throughout the year. In the early years of European colonization, livestock were generally allowed to roam free and forage for themselves. Horses, cattle, and sheep grazed in pastures and would eat the meadows clean. But pigs were the most destructive. Because their sole role was to provide meat and did not require regular milking or other tending, pigs were allowed to roam at will. Colonists notched their ears so that they could be identified later and then set them free, where they ate up food sources that normally would have gone to wild deer, elk, and other forest animals. The pigs also invaded the un-fenced crops of Native people, ate their corn, beans, and squash, and dug up food storage pits with their snouts and consumed their contents. In the fall, the pigs were recaptured, butchered, and used as a winter meat supply. Oxen were not used for meat but provided crucial power for clearing the land, plowing, and other heavy farm work, which enabled English farmers to till more land than Native Americans could.

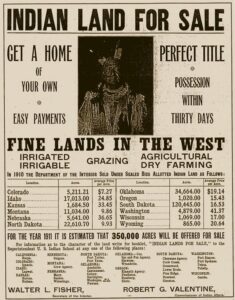

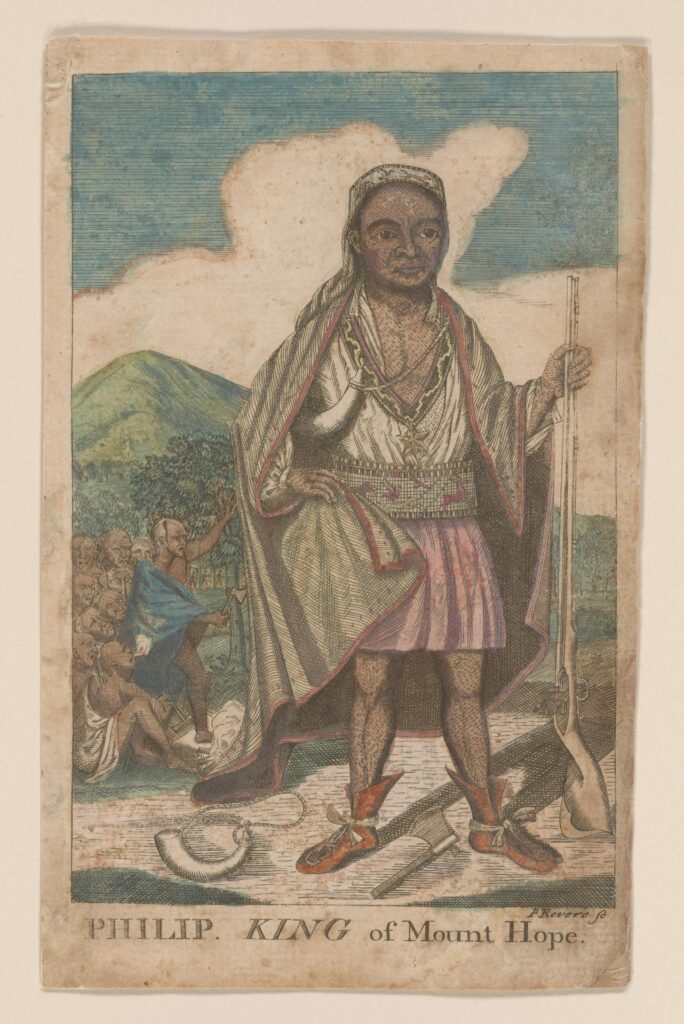

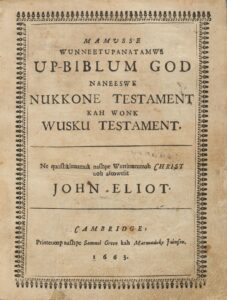

Native Americans and Europeans lived together in a single world, but fences and land ownership turned out to be too powerful to allow both groups to continue living together in the way each was accustomed. By the second half of the seventeenth century, Native Americans in southern New England had lost most of their land through war, trickery, or sale to obtain European goods. Without traditional food resources that had sustained them for thousands of years, Native Americans increasingly succumbed to disease and malnutrition. Some moved westward in an attempt to hold on to their traditional lifestyle. Others adapted to the new circumstances. They learned to use and repair European weapons, hunted in order to supply European markets (as opposed to doing so for food), raised livestock, and adopted the new agricultural practices. Still others formed new tribal alliances to resist as much as possible the colonial intrusion. But eventually, those who remained in New England were confined to reservations that sat on inferior farmland.

Starting in 1600, the rich forests that had covered New England were completely replaced within a mere 200 years. Instead, miles of fences now enclosed open land; wildlife was severely diminished; a system of country roads had been put in place; and domesticated animals fed on fields covered with clover, grass, and buttercups. The expansive global economy that the Europeans brought with them to America resulted in a total transformation of the New England landscape.

The Puritans who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony originally scoffed at how Native Americans neglected to exploit and take full economic advantage of the land on which they lived, and they used this supposed deficiency as one of their excuses to justify taking land from them. But they never considered that there could be good ecological reasons to use the land judiciously or that the seemingly unlimited resources could at one point be depleted. The radical change that they ultimately wrought on the New England landscape demonstrates the folly of this thinking. In the nineteenth century, New Englanders started to abandon the depleted soils that had succumbed to erosion on their farms and go west to take advantage of the richer soils in the Midwest. White pine trees began to replace the open fields, that is, until around 1910 when their value as timber was recognized and they were clear cut by loggers, once again transforming the New England landscape. Unfortunately, similar environmental narratives can be found in many times and places throughout the world.

Indeed, the case of the pig in colonial American serves as an apt metaphor for the treatment of the New England environment since the arrival of Europeans. Perhaps the time has come to reevaluate the philosophies and epistemologies that keep leading us into such devastating environmental practices and results.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

- Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America by Pekka Hämäläinen.

- “Teaching American History as Settler Colonialism” by Mikal Brotnov Eckstrom and Margaret D. Jacobs in Why You Can’t Teach United States History without American Indians.

- Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England by William Cronon.

- Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America by Daniel K. Richter.

- People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts by Curtiss R. Hoffman.

- “Landscape History of Central New England”: Harvard Forest website.

Click here to go to the next essay in the series, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough”

* * *

October Nature Notes

I know all about Green Eggs and Ham, but green bees? Yes, and they aren’t even wearing costumes for Halloween! Annie Reid will tell you all about these unusual and fascinating insects in her latest Nature Notes. And while you are at it, check out her other articles about the flora and fauna of Westborough in October: https://westboroughlandtrust.org/nn/nnindex?order=month#October.

* * *

What Am I Reading Now?

I recently finished reading Joseph Conrad’s novella, Heart of Darkness, where the narrator, Charles Marlow, signs up to become a steamer captain for a Belgian company to travel up a river into inner Africa to find an ivory agent named Kurtz, who has “gone native.” If the plot sounds a lot like Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, it’s because the movie is based on Conrad’s story. The novella itself comes out of Conrad’s own experience on a steamer that traveled up the Congo River and into the Belgian-owned colony of the Congo Free State, which was privately owned by King Leopold II. If you think that Coppola’s movie is disturbing, creepy, and odd, wait until you read Conrad’s story!

I know little about African history, so reading Conrad’s novella prompted me to learn more about this place and time. I am now in the middle of reading King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa by Adam Hochschild. So far, the book is fast moving and covers a lot of history that had been murky for me, such as the famous meeting of Henry Morton Stanley and David Livingstone. The book takes us back to a time when African explorers were treated like celebrities. It forces us to face tough questions about how we think about people who live in unfamiliar places and how the Western world has historically used such places and people to its own economic advantage.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.