This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Seasonal Life in Nipmuc Villages and Westborough

Village life formed the center of social, economic, and political life of the Nipmuc, the Indian tribe that inhabited Westborough and its surrounding area. Unlike villages today, Nipmuc villages moved from place to place in order to exploit seasonal diversity of food sources. A few hundred people organized into extended kin networks lived in a village, and they all worked together to support the community.

The Nipmuc lived in structures consisting of wooden frames that were covered in grass mats or bark called wetus. These houses could be taken apart in a matter of a few hours, so that they could be transported to the next site where the village would settle. Depending on the season, they would also change shape: small houses for one or two families were prevalent in the summer, whereas longhouses that could house many families were common during the winter. If there were any additional food left over before a move, it could be stored in underground pit-barns, where it could be retrieved later if needed.

The Nipmuc tended to inhabit Westborough in the Fall and then move on to some other place or places during other times of the year. They were drawn to Westborough to take advantage of the area’s lakes and swamps. No evidence exists to indicate that the Nipmuc occupied Westborough during the winter, but it is possible that they may have settled here at different parts of the season during different times of prehistory. Places where seasonal camps in Westborough have been archaeologically excavated were likely visited repeatedly over a number of years by a fair number of people engaged in short-term foraging expeditions in nearby woods.

Prehistoric people living during the Late Archaic period (4,000-6,000 years ago) mainly visited Charlestown Meadows in the western part of Westborough during the Fall, where they gathered hickory nuts, acorns, and hazelnuts, and then charred them in fires. These nuts could be stored and provided protein and fats during the winter. The Nipmuc also hunted deer and processed their kill by extracting marrow from the bones, curing the meat, and making deerskin clothing for the winter months. While in Westborough, they took advantage of its mineral resources to make stone tools and flakes. The time they spent in Westborough, though, was relatively short.

In general, food gathering resources within Westborough included hunting and trapping animals, such as rattlesnakes, deer, bear, turkey, and small mammals. Opportunities for gathering berries and nuts from hazel and oak trees were also available. Quartzite boulders could be used for tool-making. The lakes, ponds, and swamps in Westborough offered fish, waterfowl, turtles, and water snakes, and the shores of these waters provided edible greens and rich, deep soils that could have been used for farming.

Yes, farming. In my last entry to this series, I talked about some of the misnomers we hold about the life of hunter-gatherers, but I neglected to mention another one, that hunter-gatherers did not engage in horticulture. True, they did not farm the land in the way that Europeans did, with long rows of monoculture crops, but they did manipulate plants, usually within their natural environment, to shape food production to fit their needs better.

Grains, especially corn, may have made up one-half to two-thirds of the diets of Native Americans in southern New England. These crops could also be stored during the winter, which made starvation less likely. Corn is a difficult grain to grow–it requires constant weeding–which is why Native Americans raised other crops right alongside it to keep weeds at bay. Inter-planting beans (which grew up the stalks of the corn), squash, pumpkin, and tobacco among the corn prevented weeds from growing and lessened considerably the amount of labor needed to tend the crops. The result looked messy to the Europeans, who were used to planting monocultural fields, but the approach (which became known as the “Three Sisters” with the planting of corn, beans, and squash) yielded much more food per acre.

Women conducted most agricultural activities. They were also in charge of housing, owned most of the household goods, and made decisions about moving at appropriate times during the year. Men went out from these bases to hunt and fish. Food productivity reached its height in the fall months. During this time, women harvested their crops and gathered nuts and edible wild plants. Harvest festivals, where eating, dancing, and rituals took place, marked a celebration of the bounty. As part of the festivities, wealthy people gave away much of what they owned to increase their reputations, establish reciprocal relationships, and form allies and followers. (Note the entirely different attitude towards wealth here than in Western societies, where amassing capital in itself is the higher value and what one does with it is that person’s personal business.) At the end of harvest celebrations, the camps stored the harvested food and moved on to hunting grounds, where the men took over food production while the women butchered and processed the kill.

The activities of Nipmucs and other Native Americans were all focused on getting as much out of the land with as little labor as possible. In addition, each season brought different economic activity, which provided a greater variety of mental stimulation than perhaps our singularly focused jobs do today. If happiness comes from getting more from less labor, then Native Americans certainly tipped the scales in their favor.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

- People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts by Curtiss R. Hoffman.

- “A Brief Look at Nipmuc History” by Cheryll Toney Holley, in Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England, ed. Siobhan Senier.

- Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England by William Cronon.

Click here to go to the next essay in the series, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough”

* * *

Take the Nature Notes Quiz!

Every year in January, Annie Reid and Garry Kessler create a Nature Notes quiz. The idea is to use the quiz as a memory-refresher for what we all might expect to see as we experience nature in Westborough throughout the year. You can take the quiz here: https://westboroughlandtrust.org/nn/nn303.

And if you fail the quiz, like I did, don’t despair! Get out into the woods with February’s Nature Notes open on your phone to learn about our town’s flora and fauna and prepare for next year’s quiz. Or, if you prefer to lie around the house, check out the most recent Nature Notes article on Penicillium mold, which can be found in our ordinary refrigerators.

* * *

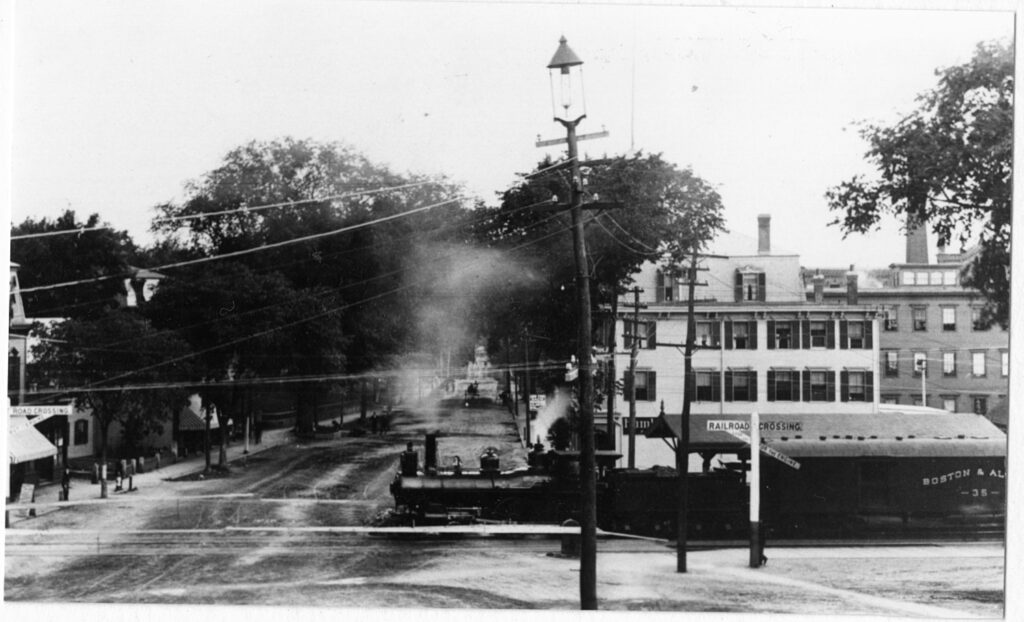

All Aboard!

The building of the railroad in 1834 turned Westborough from a serene farm town into a bustling Industrial powerhouse, a transformation that continues to influence the character of our town today. Learn all about this transition on Monday, March 6, at 7:00 p.m. at the The Willows (1 Lyman Street) when the Westborough Historical Society presents a talk by historian Phil Kittredge called, “All Aboard! The Train and Industry Pull into Town.”

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.